Seven reasons Intel could be the next RIM–and why the company is in a fight for its life

Intel’s first sales decline in 12 years is a hiccup compared to what’s coming. The chipmaker blamed sluggish third-quarter earnings, reported Oct. 16, on a PC market that shrank for the first time in 11 years, as well as broader economic slowdown.

Intel’s first sales decline in 12 years is a hiccup compared to what’s coming. The chipmaker blamed sluggish third-quarter earnings, reported Oct. 16, on a PC market that shrank for the first time in 11 years, as well as broader economic slowdown.

But there is a larger story behind Intel’s piece of the global slowdown in the growth of the semiconductor market. It’s a titanic shift in how we use technology, which could reduce one of the dominant firms in microprocessor manufacturing to a bit player chasing shrinking returns on products in which it’s forever playing catch-up. Here’s why:

1. PCs are becoming less relevant. For everything from browsing the web to acting as a cash register, a tablet is sufficient and in some cases superior at performing the jobs that we used to rely on PCs to do, and tablets are cannibalizing PC sales. By 2016, there will be 750 million tablets in use worldwide. Of those, 375 million tablets will be sold that year alone, and businesses will buy a third of them, predicts J.P. Gownder, an analyst at technology research firm Forrester. In the education sector, sales of iPads are already outpacing PCs. A new survey by Forrester found that “13% of tablet owners said they bought their tablet instead of a laptop; 18% say they’ll wait longer to buy their next laptop and 14% say they won’t buy a new laptop ever.”

2. Intel has almost none of the tablet or mobile chip market. Intel is the No. 1 chip maker in the world, with 16.5% of the global market for semiconductors. It’s undisputed king of the high-performance chips in the powerful servers that make the web possible. But in mobile devices, battery life places strict limits on how much power a processor can draw. And Intel only has 0.2% of the market for these kinds of chips. Its competitors are many: NVIDIA dominates, but Samsung and Apple now design their own chips, and even Amazon may soon be creating custom microprocessors for its tablets and (rumored) forthcoming phone.

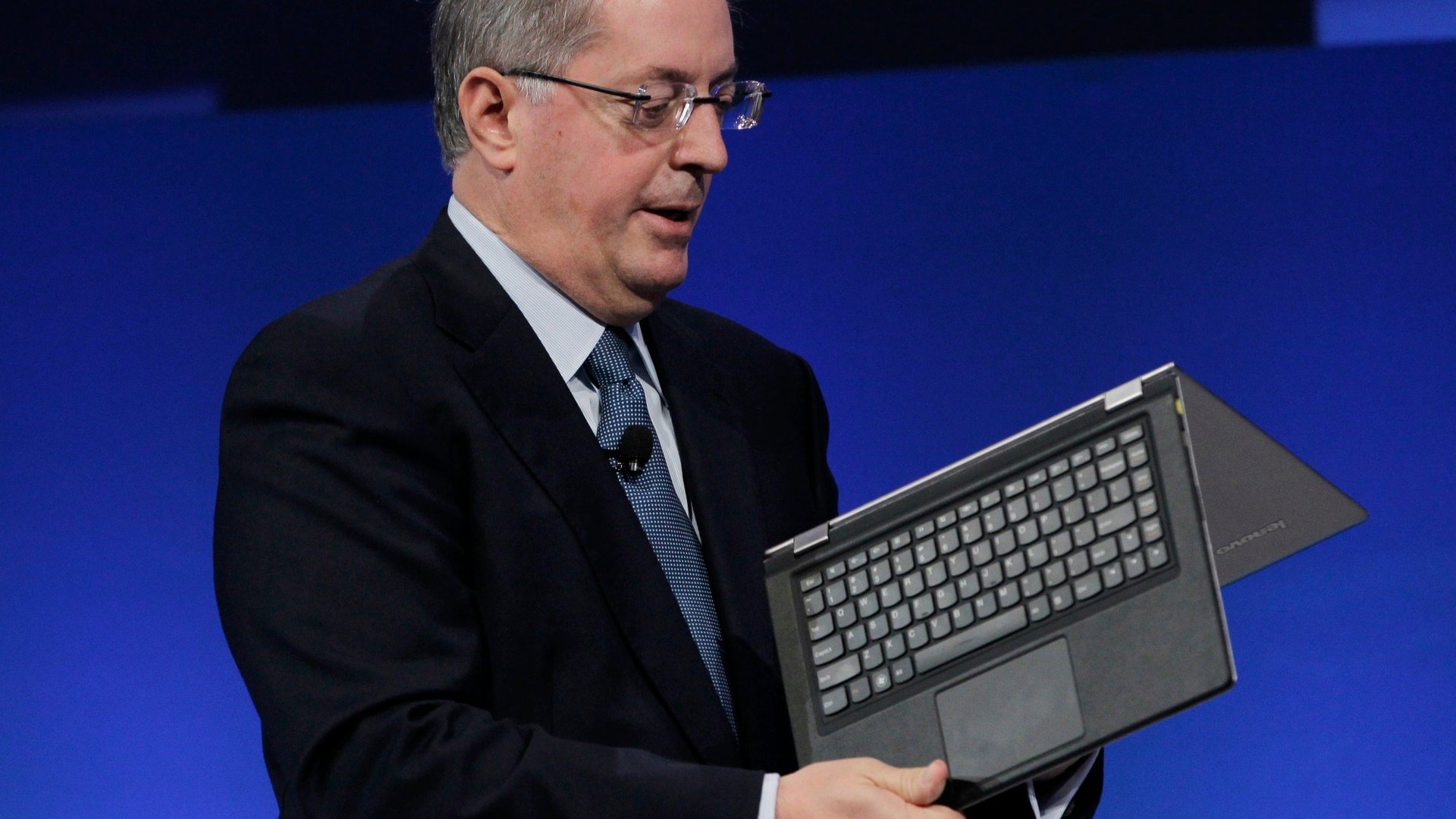

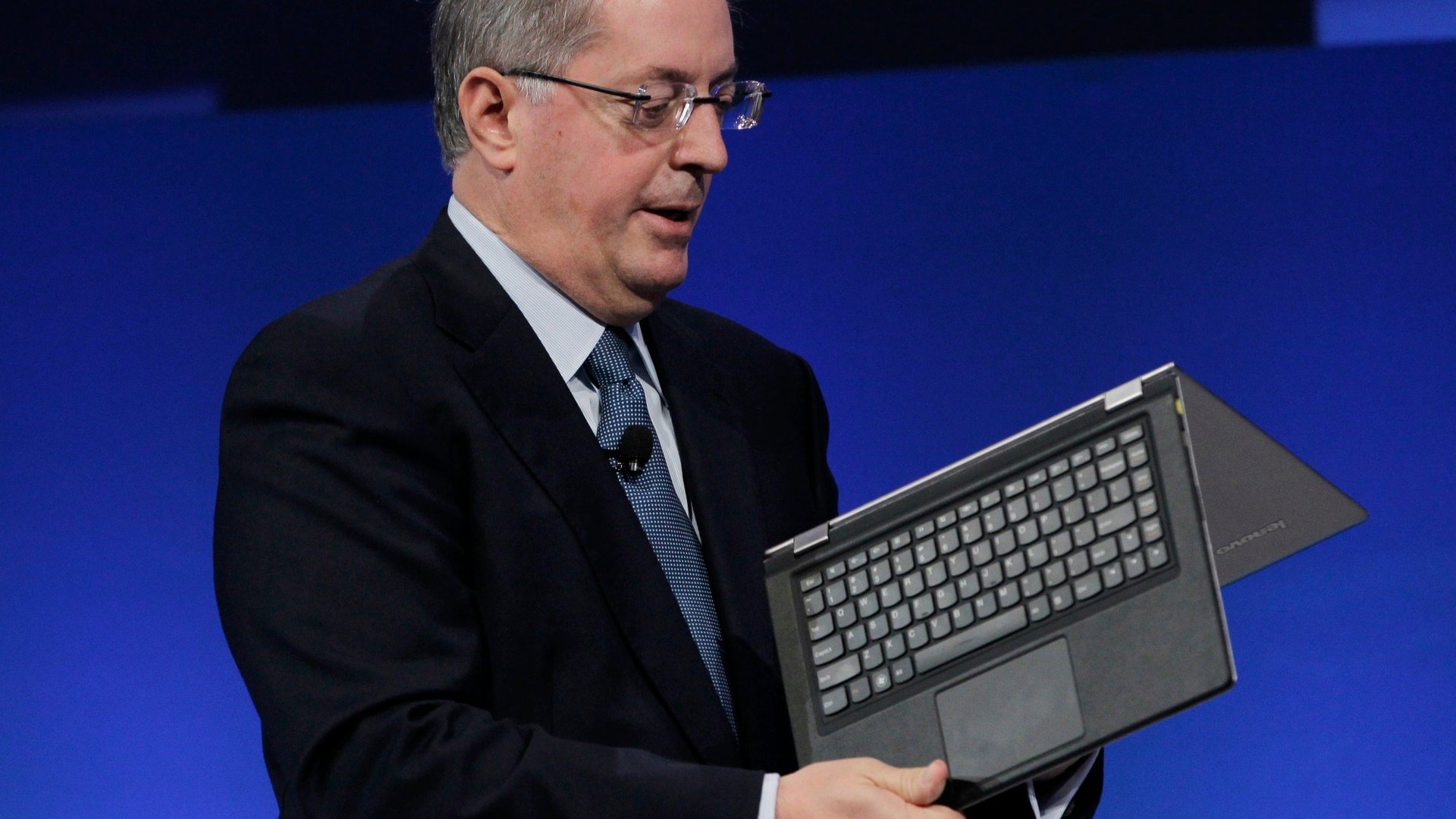

3. The move to mobile will slash Intel’s profit margins. Intel’s high-performance PC chips account for a quarter of the $1,000 price tag of the ultra-slim laptops that Intel’s partners have been trying–and failing–to sell. The chips that are the brains of most cell phones and tablets go for as little as $10 to $25, says Vijay Rakesh, a senior research analyst in charge of microprocessors at brokerage firm Sterne Agee. The Atom processors that Intel is now making for tablets running the forthcoming Microsoft Windows 8 operating system are priced accordingly, at $42-$47, but its margins on these chips are a fraction of those it makes on PC processors. ”With Atom, they have to make it work, and I think they are making it work, but the question is, will it dilute the margin structure that Intel has?” says Rakesh.

4. Not even Intel’s server business is entirely safe. As we’ve said, Intel excels at making high-end chips, which inhabit powerful computers, which live in vast and ever-growing server farms, which constitute the “cloud” where the web resides and where more and more of our computing is done every day. But the electricity needed by both the processors and the systems to keep them cool is now a dominant cost in all of those server farms. That has convinced the plumbers of the internet to figure out how to use processors not so different from the ones inside an iPhone to power the web itself. Which means that for some applications of the cloud, Intel is now fighting nearly the same battle that it has been losing in mobile devices.

5. Intel is about to lose its unique advantage. One way that Intel has long been able to keep its margins low and its technology sharp is that, unlike other microprocessor designers, it also owns the “fabs” where its chips are made. But a new fab costs some $7 billion to build, and the push to the next level of chip technology will necessitate another fab. So unless Intel can grow its market fast, it won’t have enough volume to justify building one, and will lose the edge it has enjoyed. Even if it manages that, it will be moving into a much more competitive, and less profitable, marketplace.

6. Don’t count on Windows 8 to change anything. Intel’s tablet chips will be designed for the new version of Windows, but not that many people may want to make the switch. “There’s no need for people to go to Windows 8,” says Rakesh of Sterne Agee. “There has to be a value proposition there, and Windows 8 has a new interface with its own learning curve, and most people feel the performance of Windows 7 is very good.”

7. For tech firms, flat revenue is often a harbinger of doom. ”Quarterly financial data is often a lagging indicator of strategic success,” notes Horace Dediu, a mobile industry analyst who spent eight years at Nokia. He cites the example of RIM, maker of the now much-derided Blackberry smartphone. The company’s revenues more or less tracked the growth in the mobile-phone market from 2008 through 2010, a full three years after the iPhone arrived. But as other smartphones became cheaper and the apps for them got better, people started deserting the BlackBerry in droves. In 2011, the company’s earnings fell off a cliff, and the company was suddenly worth less than its value if it were liquidated.

It seems unlikely that Intel will ever suffer precisely the same fate as RIM, since the company continues to lead in the specialized world of microprocessors for servers. As the internet grows, so too does the market for servers, and it’s not as if PCs will disappear overnight. “It’s still a market of more than 300 million PC desktops and servers sold annually today,” says Rakesh.

But, as we’ve discussed, servers too could start to use cheaper, low-power chips of the kind that Intel’s competitors make just as well. Here’s Dediu, again, on RIM and the entire mobile industry:

It might sound like a spectacular story; an anomaly, a once-in-a-lifetime reversal of fortunes. However, the moral of this story is that this is not an exceptional phenomenon. Disruption happens. It happens quickly and perhaps most quickly in this industry, and looking at trailing indicators like revenues and profits is of no help. I’ve only witnessed sharp expansions and sharp declines. I’ve never witnessed steady state, quiescent markets in technology. The history of platforms is always virtuous cycles followed by vicious declines. Whatever amplifies success seems to also amplify failure.

Intel’s success was long amplified by its mammoth chip fabs and its lead in high-performance processors. They are exactly the things that could amplify its failure.