Consider two tragic events that took place this month.

A small cell of Islamic terrorists attacked cartoonists at the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and shoppers in a Paris supermarket, killing 17 people and sparking international outcry, solidarity and support.

The hashtag #JeSuisCharlie trended globally, and world leaders took to the streets to march in support of Parisian resilience.

In northern Nigeria, meanwhile, an army of Islamic extremists razed the village of Baga, killing as many as 2,000 people—mostly women and children who were unable to flee the attacks.

Later in the week, the same army—Boko Haram—introduced a horrific new weapon of war in the nearby city of Maiduguri. They strapped explosives to the body of a ten year old girl and sent her into the city’s main poultry market. The girl was stopped by guards and a metal detector at the market’s entrance, but the bomb detonated and killed at least 19.

There has been no global hashtag campaign or march for the victims of these most recent Boko Haram massacres.

Even in Nigeria, the violence in Paris received more media attention than the massacres in Baga and Maiduguri in the three days the story was unfolding. Nigeria’s president Goodluck Jonathan has condemned the French attacks but hasn’t mentioned the slaughter in his own country.

Five weeks away from a presidential election, Jonathan may be afraid of reminding his constituents that he has led Nigeria through a year in which Boko Haram has killed at least 4,000 civilians.

Reasons behind uneven media attention

There are many reasons why the attacks on targets in Paris have received vastly more media attention than the attacks in Baga.

Paris is a highly connected global city with thousands of working journalists, while Baga is isolated, difficult and dangerous to reach. The attacks on Charlie Hebdo targeted journalists, and it’s understandable that journalists would cover the death of their comrades. The attacks in Paris were a shock and a surprise, while deaths at the hands of Boko Haram have become distressingly common in an insurgency that has claimed over 10,000 lives since 2009.

The details of the Baga attacks, where civilians fled a marauding army into the swamps of Lake Chad, where they faced attacks from hippos, are almost impossible for audiences in developed nations to empathize with.

By contrast it’s tragically easy for most North Americans and Europeans to imagine terrorists striking in their cities.

The net effect: the attacks in Baga and Maiduguri seem impossibly distant, while the attacks in Paris seem local, relevant and pressing even to people equidistant from the two situations.

In part, it’s hard to imagine events in Nigeria because we encounter so little African news in general.

Dearth of African news impacts public debate

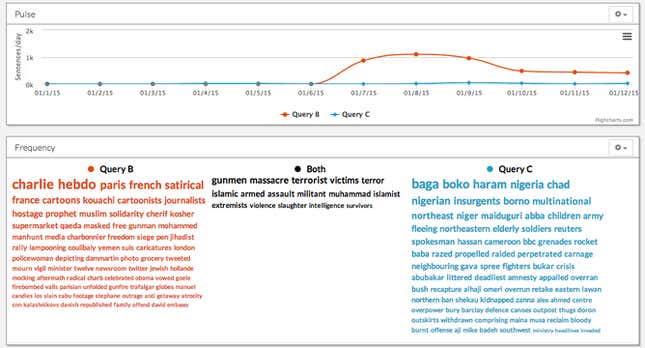

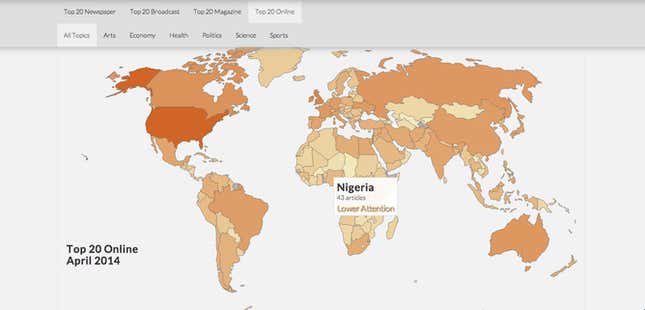

Media Cloud, a tool developed at MIT’s Center for Civic Media and Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society measures comparative attention to topics and locations in different segments of the news media.

A study we conducted in April 2014 suggests that media outlets publish three to ten times as many stories about France than about Nigeria. This disparity is striking as Nigeria’s population (estimated at 173 million) is almost three times the size of France’s population (66 million).

There’s bad news for those hoping online media will change existing patterns of media attention: while broadcast news outlets ran 3.2 times as many stories about France as about Nigeria, online media outlets published more than ten times as many French as Nigerian stories (10.4 to be precise).

We tend to read about countries like Nigeria only when they are in crisis, from terrorist attack or epidemics like Ebola. Despite the shocking magnitude of the attacks in Baga, the story can feel predictable, as the news we get from Nigeria is generally bad news.

If the attacks in Nigeria feel like they are happening somewhere incomprehensibly far away, those in Paris feel close to home, and many commentators have reflected on the tragedy in Paris as a result.

For David Brooks in the New York Times, the attacks are a reminder of the importance of dissenting and controversial views, while Teju Cole in The New Yorker argues that we can condemn the attack on free speech without supporting Charlie Hebdo’s provocative, often offensive speech.

For some, the attacks suggest that Islam is inherently violent. Others remind us of Ahmed Merabet, the Muslim policeman who died protecting the magazine or Lasana Bathily, the Muslim grocery clerk who hid Jewish customers in the freezer of the kosher grocery store to protect them, and note that the vast majority of Muslims condemn terrorism.

Whether #JeSuisCharlie or #JeSuisAhmed, millions of us apparently see ourselves as part of the tragedy in Paris.

Not so for the deaths in Baga.

We don’t know the names of parents who sacrificed themselves to save their children, or villagers who sheltered fleeing families.

Beyond Abubakar Shekau, Boko Haram’s leader, we know little about the men who’ve become this brutal army or their grievances with the Nigerian government.

And we are largely free from speculation about what the attacks on Baga mean for the relationship between secular and religious groups, between Islam and other faiths, for the stability of Nigeria and its survival as a single state.

With so little discussion of African issues in American media, it’s not surprising that most American pundits are ill-qualified to comment on the massacre in Baga. The inability of American commentators to opine meaningfully on Nigerian affairs has been the subject of one of The Onion’s most memorable parodies.

No easy answers doesn’t mean we shouldn’t pay attention

But the conflict with Boko Haram leaves few easy answers even for those following the situation closely. The most obvious course of action—supporting Nigerian armed forces—is an unpalatable recipe, as the Nigerian military has committed grave human rights abuses in pursuing Boko Haram.

In 2013, Baga suffered another massacre, this time from the Nigerian army, who burned thousands of houses and killed as many as 200 civilians, punishing the town for sheltering Boko Haram.

American military advisors have also grown frustrated with the systemic corruption of the Nigerian military and the difficulty of directing resources towards combatting Boko Haram. US forces came to Nigeria to help search for the more than 200 girls abducted from a school in Chibok in April, 2014, but by July, those forces had been redeployed.

The likely answer to combatting Boko Haram is increasing international military cooperation. Unfortunately, Cameroon, Chad and Niger – the countries most directly threatened by Boko Haram—have recently withdrawn troops from the region. Chad, for example, has already seen more than 7,000 refugees from Baga seek shelter across the border.

Without an easy answer to the conflict or an ideological point to tie to the tragedy, the response to those who’ve heard of the massacre in Baga is a mournful silence.

That’s not enough.

The hundreds or thousands dead in Baga demand our grief as fellow human beings. They demand our scrutiny so that Nigeria’s leadership cannot escape the consequences of their failure to end this conflict, or the abuses the Nigerian military has committed. And they demand our attention, so we understand the shape of religious extremism in the world.

Most victims of Islamic terrorism are Muslim: between 82 and 97%, according to a study from the US National Counter Terrorism Center.

Attacks like the one on Paris are shocking, visible and rare, while attacks on Baga are common (though the scale of the Baga attack is unprecedented.)

When we understand extremist violence as attacks on urban, developed, symbolic targets, we’re missing a much broader, messier picture, where religious extremism blends with political struggles and where the victims are usually anonymous, uncelebrated and forgotten.

We miss the point that Islamic extremists are at war with other Muslims, that the source of terror is not a religion of 1.6 billion people, but a perverse, political interpretation held by a disenchanted few.

It’s right to mourn those killed in Paris, to celebrate the city’s resilience and to honor the heroes. But if we fail to mourn and to understand Baga as well, we see a picture of terrorism that’s simple, clear and deeply inaccurate.