The Patel protests are a slap in the face for Narendra Modi’s vibrant Gujarat

Gujarat’s influential Patel—or Patidar—community has rattled the western Indian state in the past few days with its demand for other backward class (OBC) status.

Gujarat’s influential Patel—or Patidar—community has rattled the western Indian state in the past few days with its demand for other backward class (OBC) status.

At least eight people have died in incidents related to the agitation, curfew has been declared in over half-a-dozen cities, paramilitary forces have been deployed and the army has been called in to conduct flag marches.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government—which has ruled Gujarat with the staunch backing of the Patels—has been taken completely off guard.

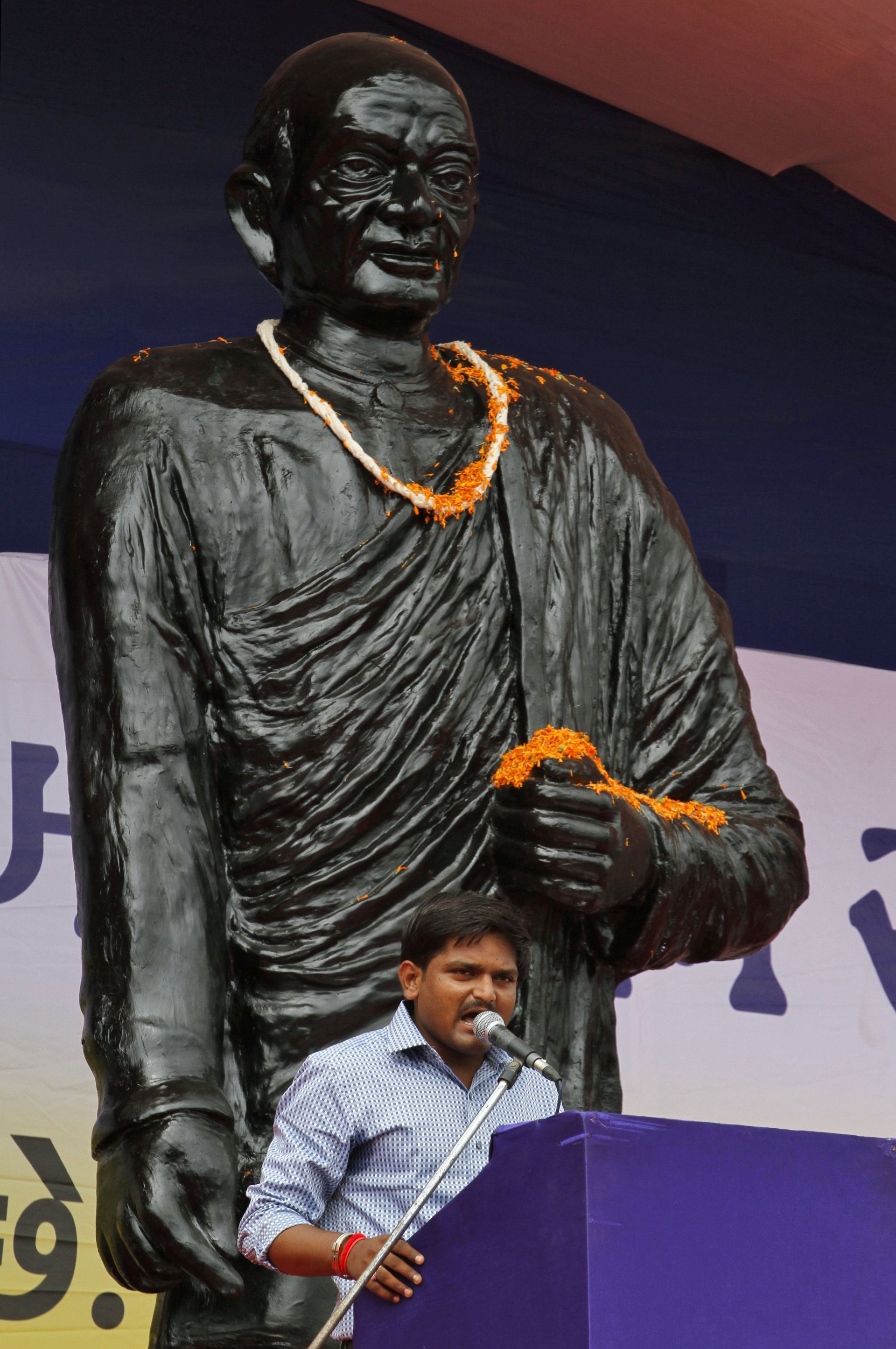

Prime minister Narendra Modi, who served as the Gujarat chief minister between 2001 and 2014, has appealed for peace, but the protestors, led by a 22-year-old commerce graduate, have promised that they won’t back down.

But why exactly is an economically successful community in an industrialised state like Gujarat agitating for caste-based quotas?

And what does it mean for the likes of the BJP, which has dominated the state’s politics for decades?

In an interview to Quartz, Achyut Yagnik, a social scientist and author based in Ahmedabad, argues the protests are a manifestation of the flaws in the development model mastered by Modi.

Yagnik’s answers below have been lightly edited for clarity.

What is the history of the Patel uprising?

Patels are the surname of people who belong to the Patidar community. Patidars were an agrarian community in the 19th century and the word patidan meant entitlements. They were primarily a middle class community. During the 20th century, they supported the Indian National Congress party at the time of the independence movement, following Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Once the agriculture business took off, they set up small and medium-scale industries across the state.

In the 1980s, when Gujarat was at the brink due to reservation policies, the Patels had strictly opposed it. The then government, led by Madhav Singh Solanki from the Congress party, had come up with an electoral strategy of focussing on the KHAM (Kshatriyas, Harijans, Adivasis and Muslims). This alienated the community from the Congress and they moved to support the BJP. Since then, they have been the BJP’s mainstay.

They felt deprived and fought the government against the reservation policy back then. But now, they have done a 360 degree turn and want to be brought under the reserved category.

How powerful are the Patels?

In the current state assembly, 40 of the 120 BJP MLAs (members of legislative assembly) are Patidars, and even the powerful home minister and chief minister belong to the Patel community. The president of the BJP in Gujarat is also a Patidar. Before Modi became chief minister, there was a Patel, and after he left, there is a Patel as chief minister. It is such a dominant community. It is funny how they are asking for reservation.

The community is financially well-off. They own cooperative societies, the dairy industry and a lot of diamond trade. I think it is more like an anti-reservation protest.

It is the younger generation of Patels who are getting restless. They aren’t getting jobs. They haven’t been able to get into medical colleges, and at the end of the day, many aspire to move to the US. One-third of the Indians in the US are Gujarati, and a majority of them are Patels. The younger generation in rural areas want to live in urban areas and they want the opportunity now, which they are being deprived off.

Why are they protesting now?

There are basically two reasons for the current uprising.

The Patels had set up a lot of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) across Gujarat in Saurashtra, Jamnagar and Rajkot. These survived on governmental support for years. But, with the Gujarat model of development, the Modi government laid stress on big industries. In the past ten years, some 60,000 of these SMEs have shut down.

Even the diamond business, where many are engaged, has been facing a slowdown.

The second aspect is the problem of jobs. The government has been giving away jobs under the contractual programme (instead of permanent jobs). For instance, in education, vidya sahayaks, who are contractual teachers, get about Rs7,500 per month. Contractual jobs were also extended to land revenue department and police forces.

Within the Patel community, there are also a number of them who are middle class. They are interested in securing jobs as teachers or in the government services. For instance, in Kutch, you will find a lot of Patel teachers who hail from the Mehsana district, which is also the epicentre of the protests. So when contractual jobs were being awarded, many became unhappy.

Indirectly, the protests are a take on Gujarat’s model of development that has failed. And Narendra Modi is responsible.

What does this mean for the BJP?

Patels have been the backbone of the BJP since 1985. And now, they are an all-powerful community in the party and the government. But the younger generation doesn’t care. On Aug. 25, they set fire to the house of Rajni Patel, Gujarat’s home minister. He is also a Patel.

Within the Patels, grandfathers support the BJP, but the grandchildren don’t.

Also, the current government lacked vision. Hardik Patel had raised the issue on May 6 this year, but the BJP government didn’t do anything. Indirectly they were supporting it till it hit them hard on Aug. 25. How could they have managed the protest without any sort of approval from the top? But they did not think Hardik would create such a ruckus.

And now, the backbone of the BJP has been broken. In the future, Patels won’t vote for the BJP—and that is a big setback.

Can the Congress party seize the opportunity?

Congress is structurally weak in Gujarat. Their main support is the OBC, scheduled caste and scheduled tribe. They are not in a position to directly intervene. My sense is there is unhappiness within the Congress party about its state leadership, too. So there won’t be an opportunity for them.

Who is responsible for the problem?

The whole uprising is a failure by Modi. He ruled the state for 13 years.

He developed the big industries at the cost of SMEs. Economically, Gujarat is going through a tough and problematic phase. The social fabric has been affected—and that’s very dangerous.

What happens next?

They cannot afford to give any more reservations. At this point, Brahmins and Banias in Gujarat are about 3% each of the population. Another 5% are Kshatriyas. About 45% of the population is backward classes. Patels are about 15% of the population. In reality, they are upper class.

The Dalits in the state are now worried. There is an underlying fear because of the protests since they believe they will be targeted, and it is impossible for the government to fix the current crisis. The law does not allow more than 50% reservation. There is 27% reservation for the OBC, 15% for tribals and 7% for Dalits in Gujarat.

This whole fiasco will create a big challenge for the BJP, and they will face problems in the elections. Indirectly, all of this is a failure of Gujarat development model. There is a myth that has been created about the model and now there is a demystification that’s going on.

This uprising is a game changer for Gujarat, Modi, and for the BJP.