This recycling bin is following you

Recycling bins in the City of London are monitoring the phones of passers-by, so advertisers can target messages at people whom the bins recognize.

Update (Aug. 12):

City of London halts recycling bins tracking phones of passers-by

Recycling bins in the City of London are monitoring the phones of passers-by, so advertisers can target messages at people whom the bins recognize.

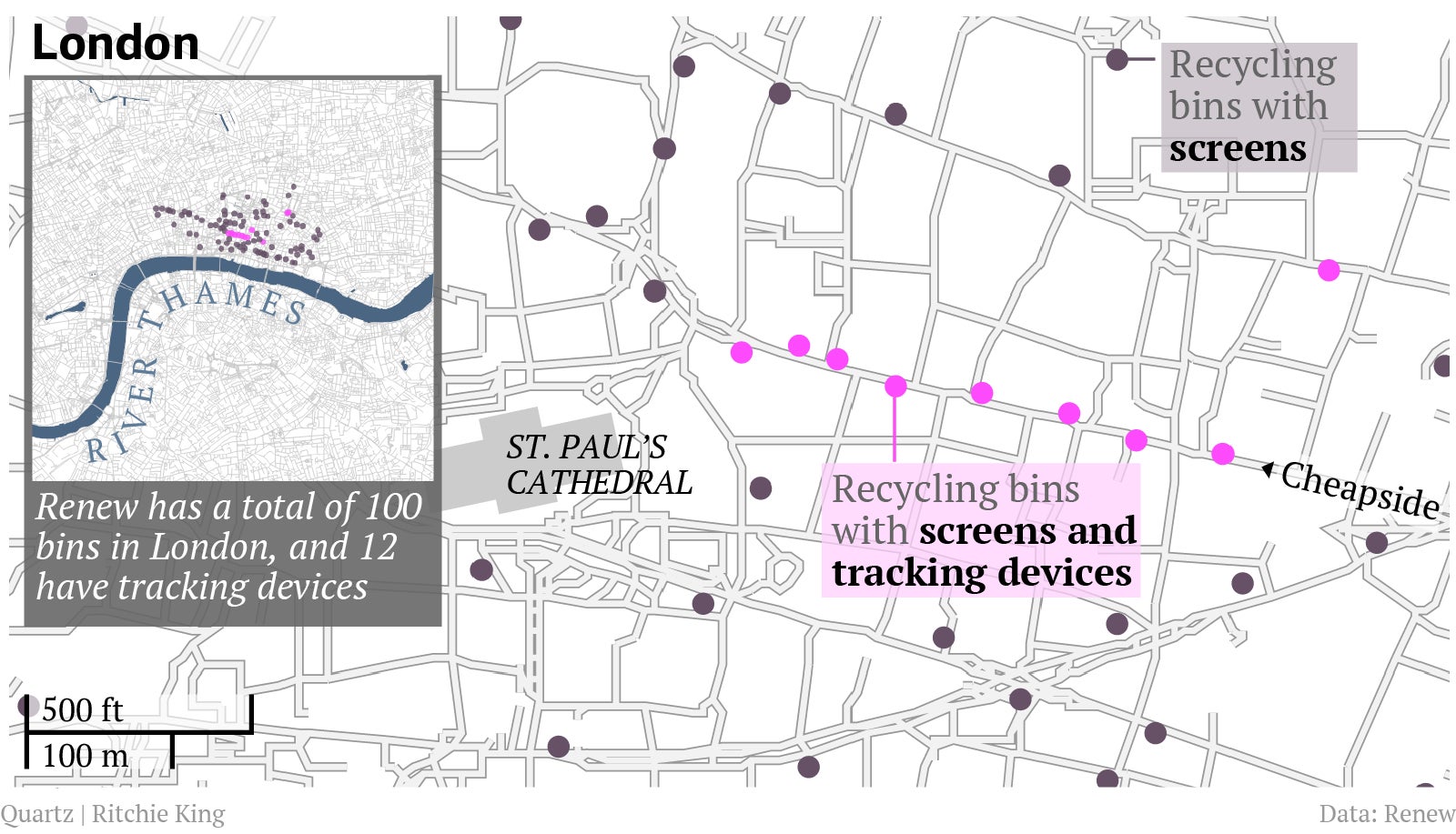

Renew, the startup behind the scheme, installed 100 recycling bins with digital screens around London before the 2012 Olympics. Advertisers can buy space on the internet-connected bins, and the city gets 5% of the airtime to display public information. More recently, though, Renew outfitted a dozen of the bins with gadgets that track smartphones.

The idea is to bring internet tracking cookies to the real world. The bins record a unique identification number, known as a MAC address, for any nearby phones and other devices that have Wi-Fi turned on. That allows Renew to identify if the person walking by is the same one from yesterday, even her specific route down the street and how fast she is walking.

Here, an image from Renew’s marketing materials makes it plain:

The technology, developed by London-based Presence Aware, is supposed to help advertisers hone their marketing campaigns. Say a coffee chain wanted to win customers from a rival. If it had the same tracking devices in its stores, it could tell whether you’re already loyal to the brand and tailor its ads on the recycling bins accordingly. ”Why not Pret?” the screen might say to you. Over time, the bins could also tell whether you’ve altered your habits.

This kind of personalized advertising was famously envisioned in the movie Minority Report—except, in this real-life example, brands are scanning iPhones instead of irises. Retailers like Nordstrom have tested similar technology in their stores, the revelation of which sparked a minor outcry. Kaveh Memari, CEO of Renew, doesn’t think what his company is doing violates anyone’s privacy.

“From our point of view, it’s open to everybody, everyone can buy that data,” Memari told Quartz. ”London is the most heavily surveillanced city in the world…As long as we don’t add a name and home address, it’s legal.”

In the European Union, websites are legally required to inform users if a tracking cookie is placed on their computer. Tracking smartphones and other Wi-Fi devices isn’t nearly as regulated, in part because the technology is so new.

Renew would like to expand the technology to all of its recycling bins in London as well as those in New York City, Dubai, and Kuala Lumpur. In its test this summer, Renew installed the tracking devices in 12 of its London bins, most of them along a stretch of Cheapside, a busy street lined with retail stores:

The company still needs to sell retailers on the concept. Memari said he was working on a proposal for a bar that would install five tracking devices: one by the entrance, one on the roof, one near the cash register, and one in each of the bathrooms. That would allow the bar to know each person’s gender (from the bathroom trackers), how long they stay (“dwell time” is the official metric), and what they were there for (a drink outside or a meal inside). And targeted advertising for the pub could follow those people around London on Renew’s omniscient recycling bins.

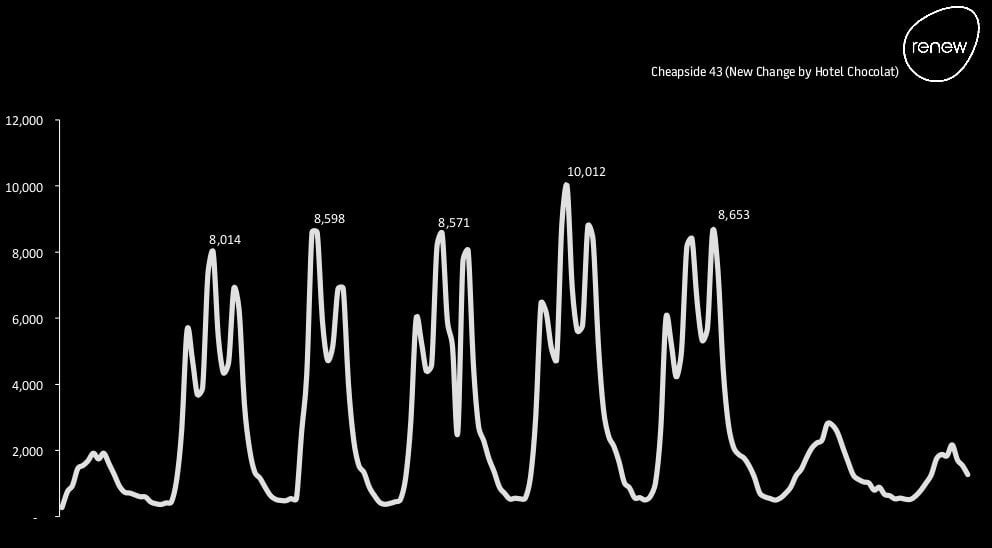

In the first month after installing the trackers, Renew says it picked up over a million unique devices. On July 6, a record day, its bins identified 106,629 people, taking note of their presence 946,016 times, according to the company. This chart, provided by Renew, shows one recycling bin’s readings over the course of a week, with spikes during commutes and lunch:

Memari notes that MAC addresses, while unique, don’t reveal the owner’s name or other identifying information. He says companies like Facebook and Google collect more information about people. Of course, those sites have terms and conditions of use, even if few people read them. In theory, MAC addresses could be paired with other consumer data collection, like a supermarket loyalty card, which could reveal the person’s name. Memari says that would go too far.

It’s possible to avoid one’s phone being tracked by turning off Wi-Fi on the device or filling out an online form. Memari says 80% of people in London leave Wi-Fi on when leaving their home or office.

“The chances are, if we don’t see you on the first, second, or third day, we’ll eventually capture you,” he said. “We just need you to have it on once.”