QE3 is Ben Bernanke’s masterstroke of market manipulation

It’s never been so profitable for US banks to give mortgages.

It’s never been so profitable for US banks to give mortgages.

Yet they’ve almost never been so reluctant to do it.

So now, the Fed is forcing them.

Much has been written about the Fed’s announcement of its latest effort to support the US economy with a new round of money creation and mortgage-bond buying—QE3—on Sep. 13. But few have recognized that it amounted to a shot across the bow of some of the biggest financial institutions in the country.

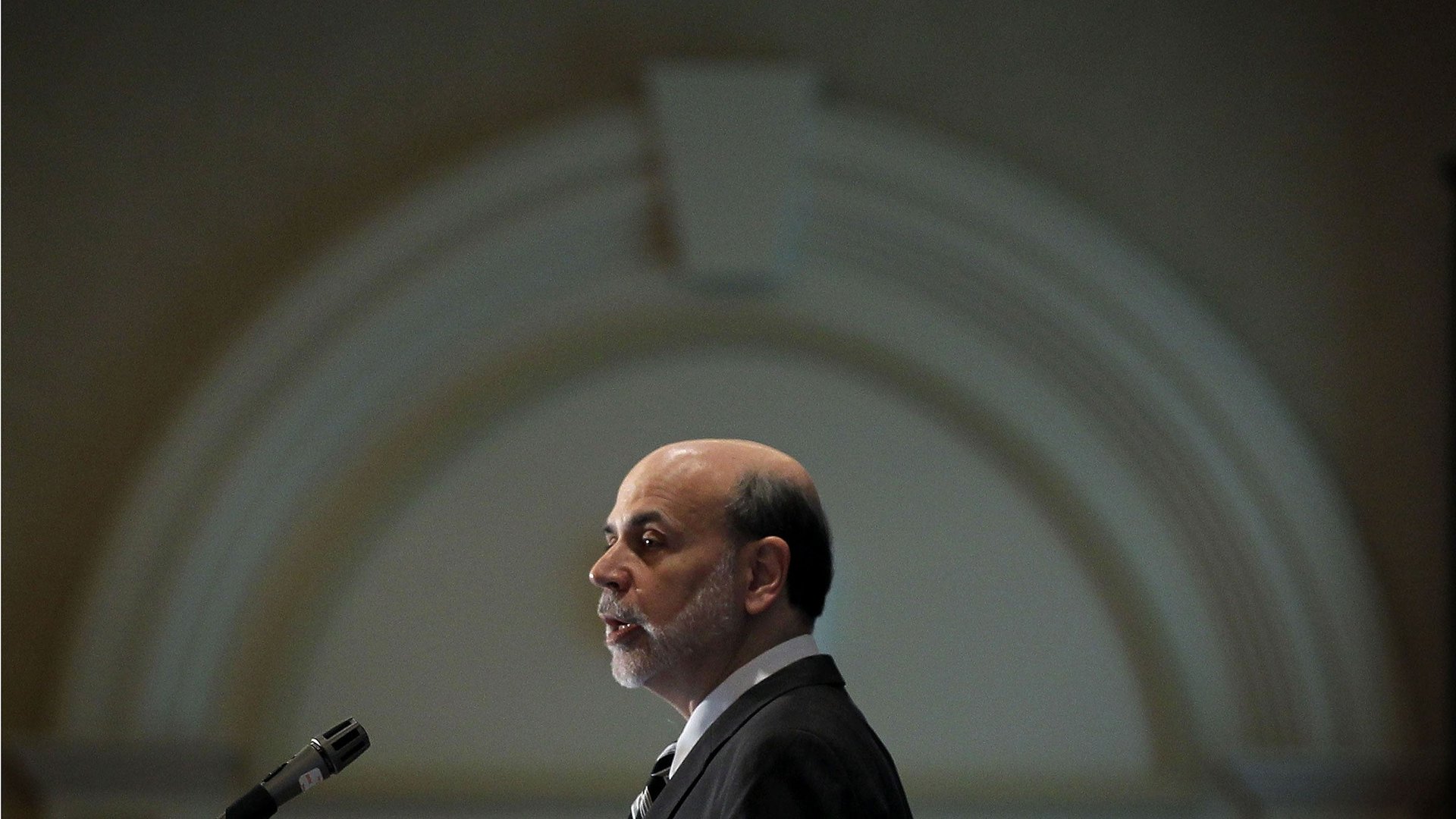

Here’s why. The Fed is aiming its unlimited buying power (since it can literally create money) at the market for mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the pools of mortgages where nearly all American home loans eventually end up. And the one of the largest holders of these MBS are the banks.

Banks have loaded up on MBS over the last couple years, for two very good reasons. First, MBS (certain kinds of them, at least) are very safe. The mortgage bonds of the giant housing-finance agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are considered as safe as US Treasurys, since these agencies are effectively under the wing of the US government, which bailed them out during the financial crisis. Better still, MBS pay a higher return than Treasurys do. Super-safe and higher-yield is an irresistible deal.

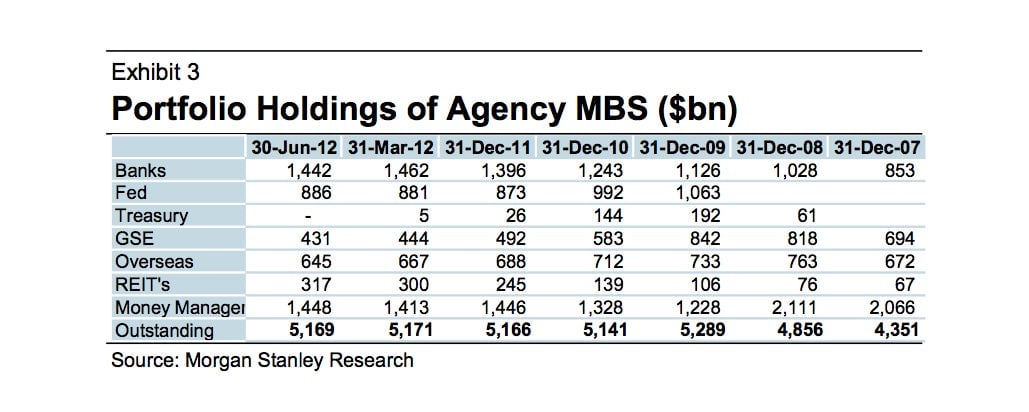

The result? The MBS holdings of large commercial banks are up 32% since the end of 2009—that’s the red line in the chart below. That’s outpaced the growth in other bank investments, especially that saw-toothed blue line at the bottom, which are real estate loans.

This is where QE3 comes in. The Fed says it will buy mortgage bonds. It has massive buying power. That pushes up the prices of the bonds. And at a certain point, the idea is that the banks won’t be able to resist. They’ll bite, selling their bonds, and collecting a big pile of cash.

But after a few high-fives around the boardroom table, the bankers realize they now have another problem. They’ve got a pile of cash they’ve got to invest profitably. And there aren’t a lot of good places to go. Why don’t they just go buy more MBS?

They could. But remember, MBS are more expensive now. And in the world of bonds, prices and investment returns move in opposite directions.

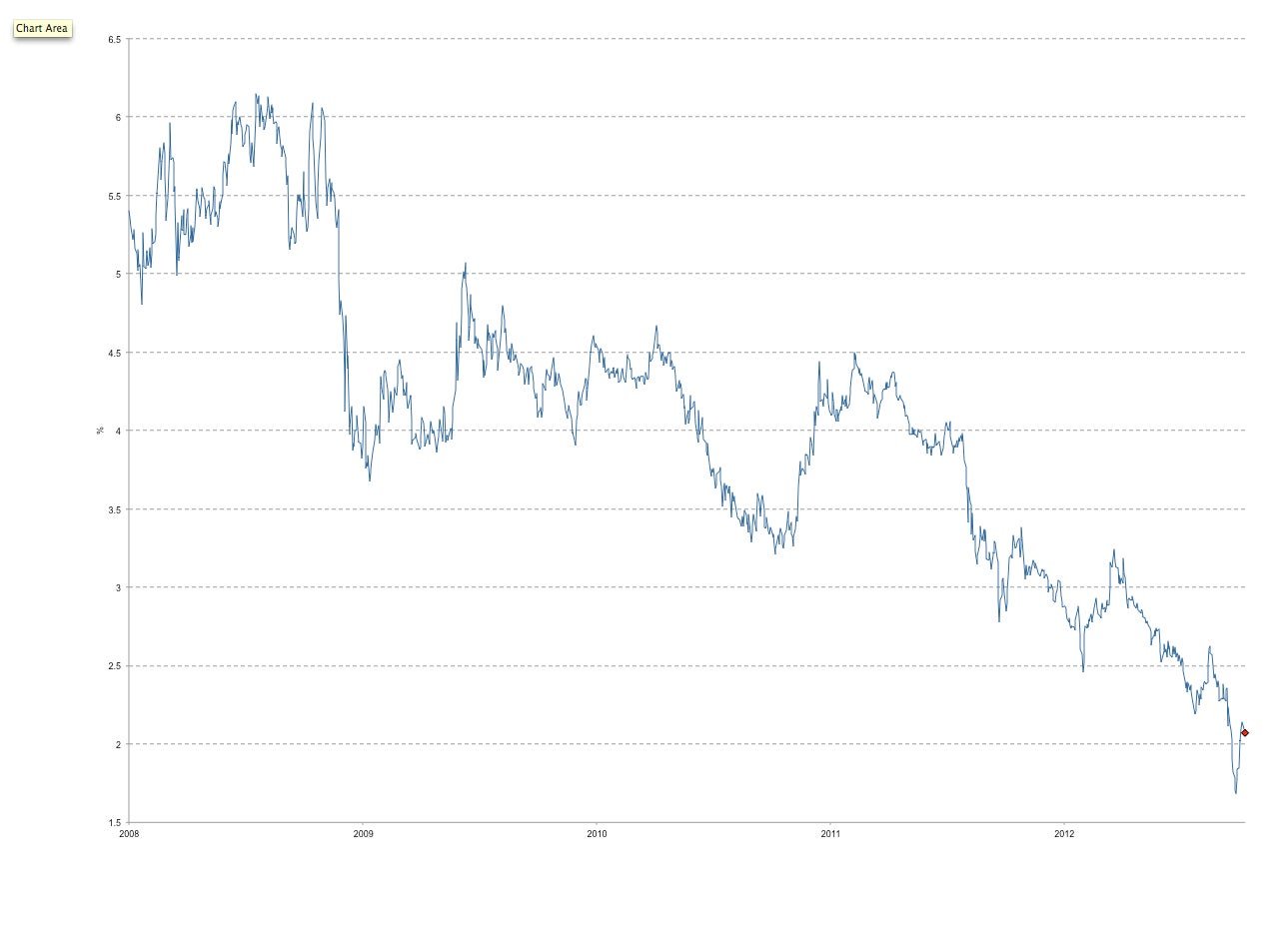

And QE3 has been hugely successful in driving down the yields on mortgage bonds. A good gauge of these yields is known as the “current coupon” yield. Basically, it’s the going yield on a mortgage bond that would be stuffed with the mortgages banks are currently giving out. Mortgage interest rates have been going down. So the return on these bonds is looking skimpier and skimpier:

This really stumps our bankers, who are still sitting at the boardroom table looking at their massive pile of money. Think, bankers. Think. What could you possibly do with a giant pile of money that you need to make a return on? Banks aren’t like other investors. Because of regulatory constraints they can’t bet the farm on the stock market or highly leveraged gold ETFs. (Though they’d probably like to. ) Isn’t there some complicated derivative trade they could put it on? There’s got to be something. Suddenly a scrawny junior executive has an idea. It’s something bankers used to do in the old days. He saw it in a movie once. What was it called again? It started with an “L.”

Oh, yeah. “Lending.”

The older bankers chortle to themselves. Lend? You can’t possibly make money lending. The interest rates on mortgages are going down, remember? They’re at historic lows not seen since the aftermath of World War II.

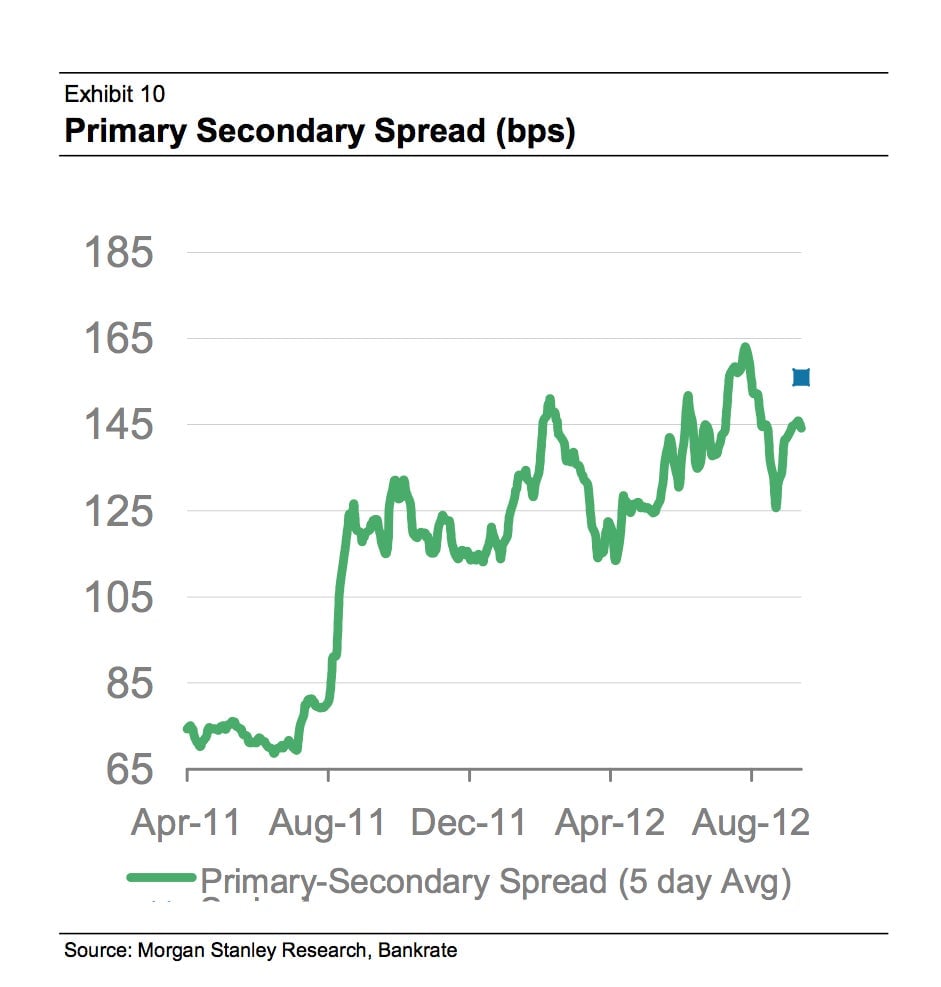

But believe it or not, it has never been more profitable than to lend money for mortgages than right now. The chart below shows the primary/secondary spread. This is the difference the average mortgage rate consumers are offered and the benchmark rate on mortgage bonds in the financial markets, it serves as one gauge of the potential profit a bank can make on a mortgage. This spread has hit record highs recently.

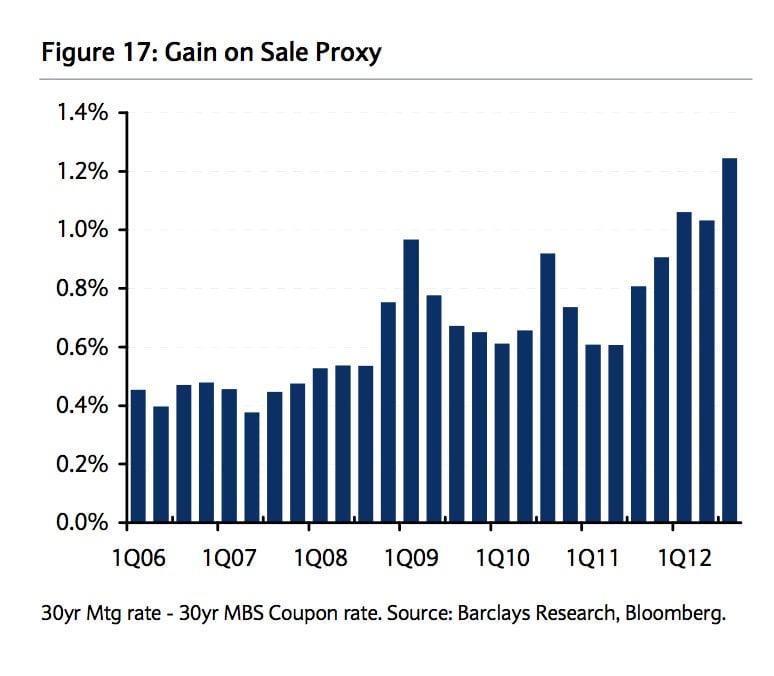

Another measure of the profits banks can earn from mortgage lending is known as “gain on sale.” It’s the profit US banks make from giving a home loan and then selling it into the secondary market. As you can see, it’s way more profitable to make mortgages now than it was during the peak of the housing frenzy. This is because at that time banks were competing like crazy to make new mortgages, driving profit margins way down.

Slowly its dawning on our bankers. As a result of the Fed, buying MBS, while safe, is the least attractive it has ever been. On the other hand, also because of the Fed, actually lending money to people that want to buy houses is the most attractive that it’s ever been. After several PowerPoint presentations, our Harvard Business School MBAs think they know what the right business move will be. It sounds crazy. Maybe a little visionary. But they’re actually going to lend people money to buy houses.

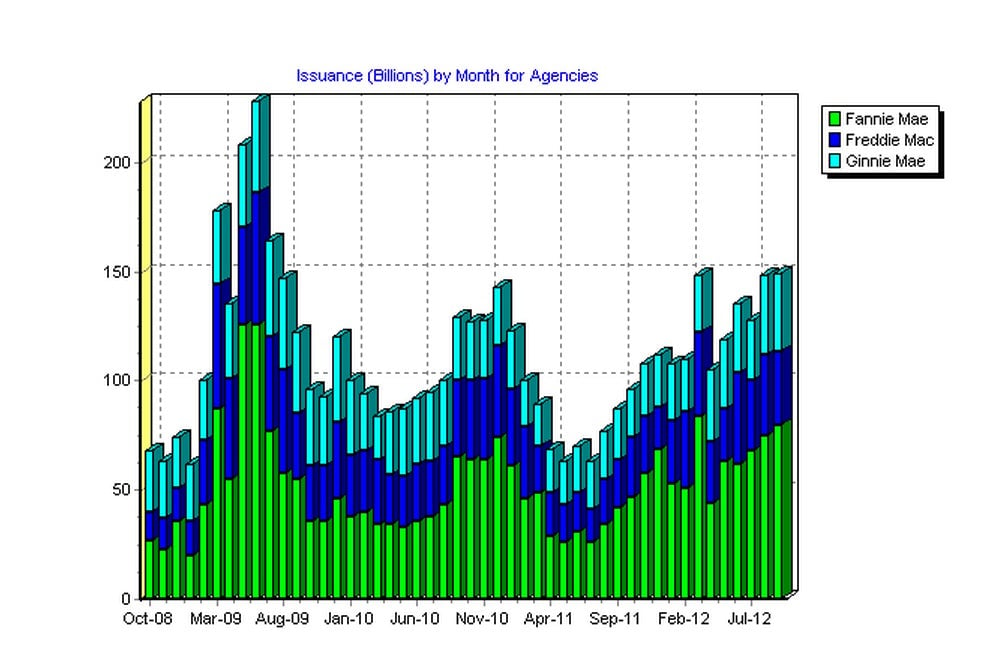

And that’s what we’ve seen. The best general measure of lending activity, the monthly mortgage issuance in Fannie and Freddie’s MBS, has been picking up, according to data provider eMBS.

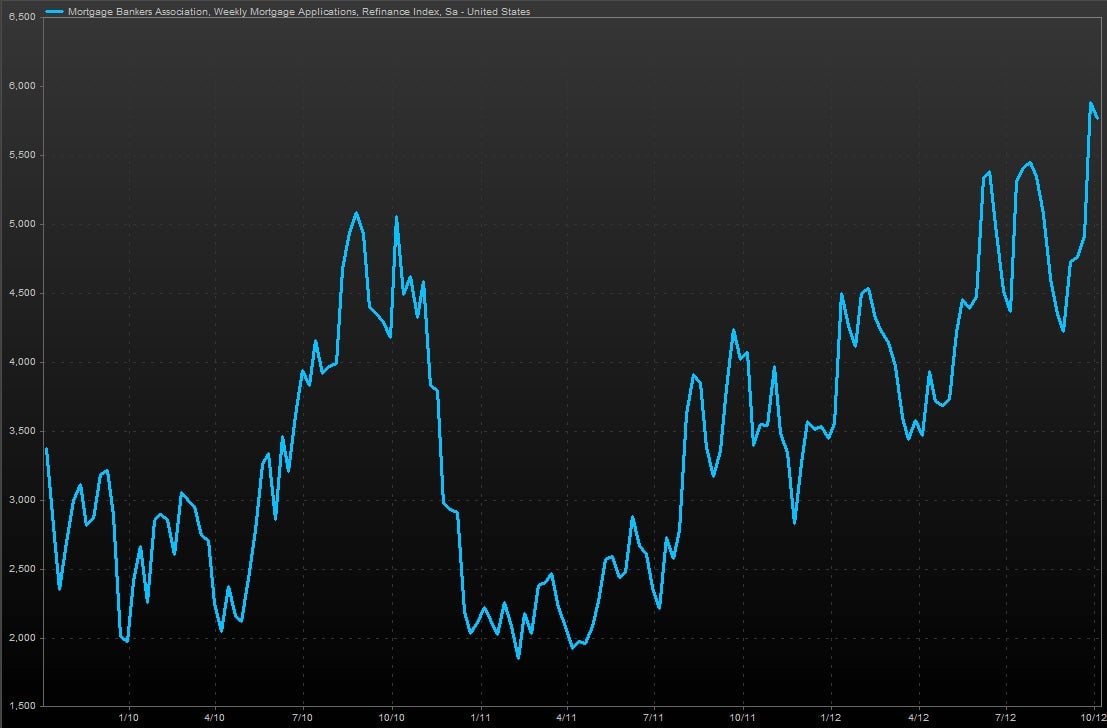

And the pace of refinancing activity is accelerating, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association’s refinancing index.

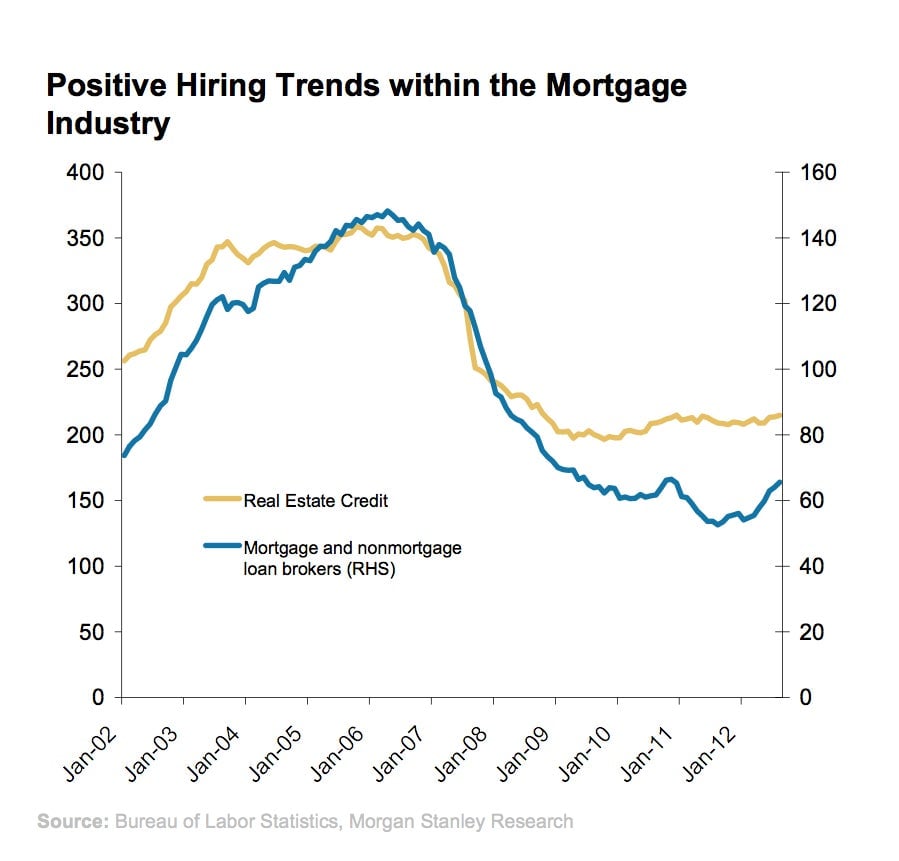

And there are even some signs that mortgage lenders could be starting to hire people again. Morgan Stanley analysts say that employment at lenders is up 7.2% from this time last year.

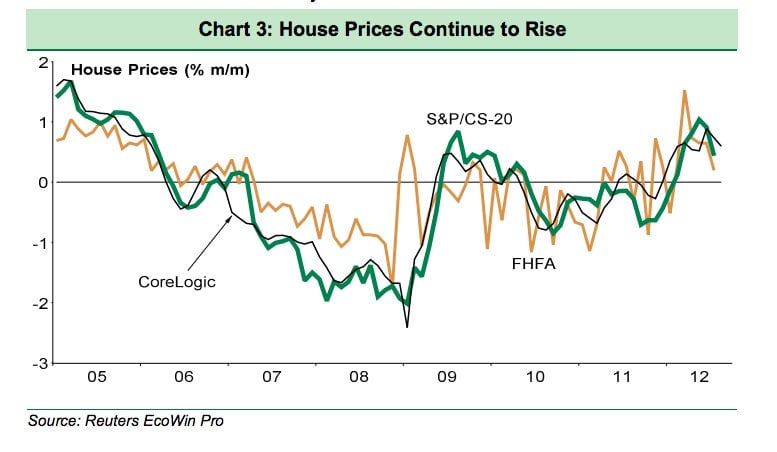

These are all tremendously good things for the US economy. The more people refinancе at lower mortgage rates, the more it cuts their monthly housing outlays and frees up cash to be spent elsewhere. The surge in activity helps support gains in home prices. As home prices rise, more people will re-emerge from being “underwater” on the mortgages—owing more than the house is worth—a condition that usually makes them ineligible for refinancing. That opens up a whole new rank of people who are now able to refinance. This is what the start of a virtuous circle looks like.

Let’s be clear. The US economy is far from being out of the woods and unemployment is still too high. But if things continue to roll the Fed’s way, the central bank’s focus on buying mortgage-backed securities—which simultaneously makes it more attractive for would-be home owners to borrow and for banks to lend—might just go down as Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s masterstroke of market manipulation. And that could be an inspiration to other central bankers — from the BoE to the ECB — trying to prove they remain relevant.