This Christmas could be make-or-break for Toys “R” Us

Toys “R” Us might not have too many Christmases left, at least if you listen to what the bond market is saying.

Toys “R” Us might not have too many Christmases left, at least if you listen to what the bond market is saying.

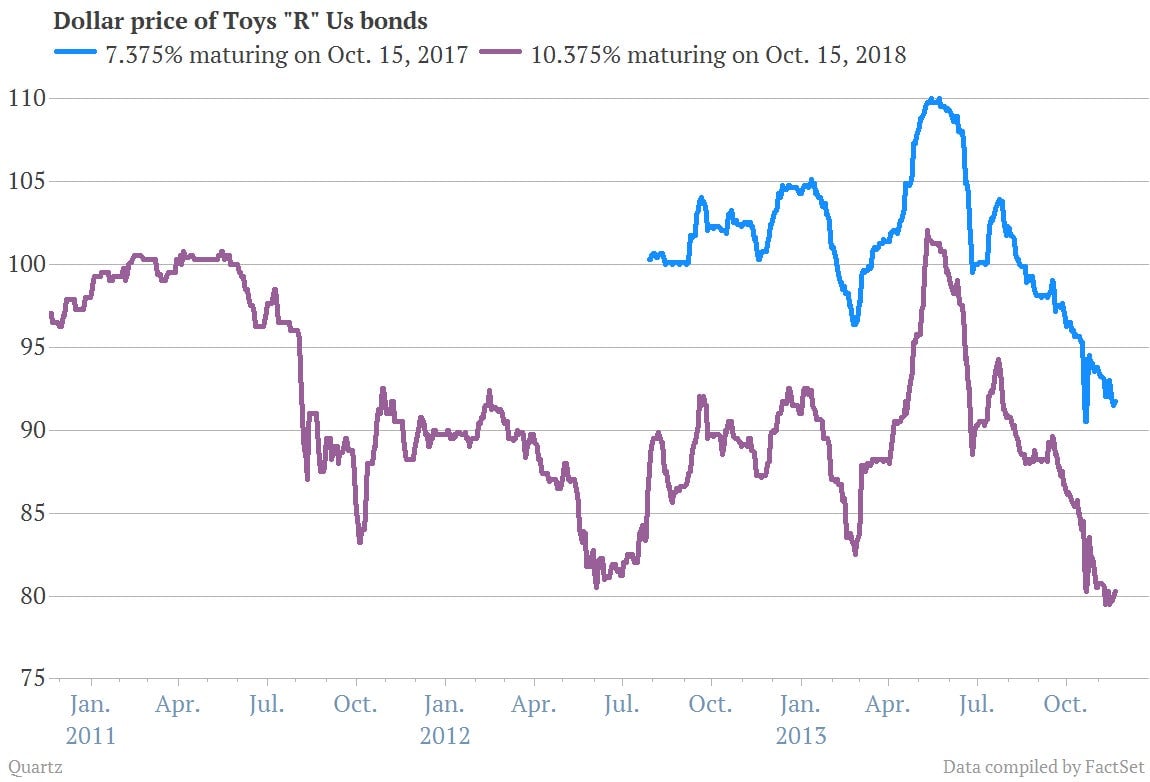

Investors have been dumping obligations owed by the largest US toy retailer in recent months, pushing the dollar price of those bonds sharply lower. Take a look:

Bond market watchers at Moody’s Analytics—a separate arm of the company from the group that actually rates the bonds—have been watching the dropping prices carefully. They say the price declines “imply that investors may well consider the upcoming holiday season to be a make-or-break time for the company.”

In fact, Moody’s analysts say Toys “R” Us bonds are trading at such low prices, you’d typically expect to see them on the bonds of an entity with a single “C” credit rating. That’s four notches lower than the “Caa1” rating that Moody’s credit-rating arm has assigned to Toys “R” Us.

“Single C is the lowest notch on the ratings scale,” said Jerry Tempelman, an analyst with Moody’s Analytics who’s been watching the performance of Toys “R” Us securities. “Even Caa1 is considered deep junk, but single C is as low as it gets.”

According to Tempelman, Moody’s Analytics looked at some 262 other instances when such a four-notch negative discrepancy has occurred since 1999. The result? Around 80% of the time, the company had defaulted within three years. Toys “R” Us didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

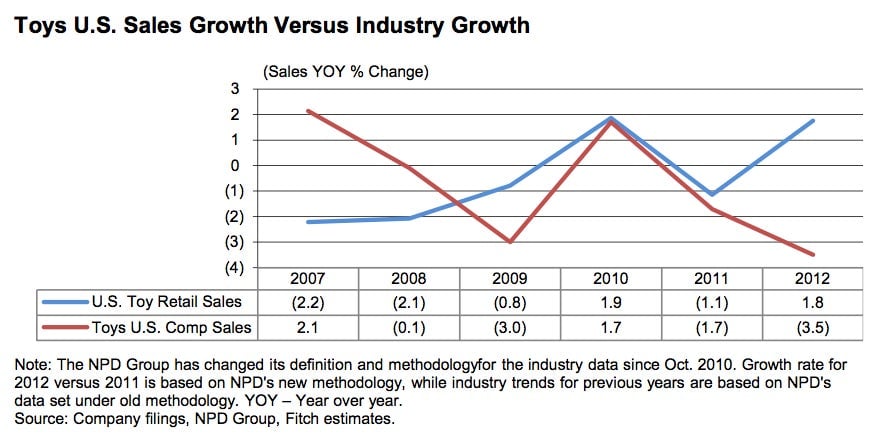

How did Toys “R” Us, the largest standalone toy store chain in the world, find itself in this situation? A time-tested melange of sluggish sales and high levels of debt. As a brick-and-mortar retail operation, Toys “R” Us has seen its market share slip thanks to the likes of online giants like Amazon.com. Meanwhile, traditional hot sellers such as stuffed animals, puzzles and board games have slumped as electronic games have spread. Video game sales plugged the gap for a little while, but mass market retailers such as Target and Wal-Mart have been eating into that business in recent years.

Meanwhile, the company is laboring under mountains of debt. Is this because of imprudent, spendthrift management? Not really. It’s mostly because the company was taken private in a 2005 leveraged buyout (LBO) led by Bain Capital, KKR and real estate company Vornado. (For a great recap of the deal, read this New York Times piece.)

As a quick refresher, in the 1980s KKR pretty much invented the leveraged buyout business, in which investors buy a company by putting up a relatively small sliver of their own money. How? They use the property and financial assets of the company they want to purchase—in this case Toys “R” Us—as collateral against which they can borrow. And they borrow big. These giant debts usually aren’t a worry for the acquirers, as they aim to get out of the investment within a few years, usually by selling the company to the public in an IPO. Nor are they a big concern for the executives that agree to sell the company off. (CEOs often reap sizable rewards for selling off their firms.)

That was the plan with Toys “R” Us, too. Bain, KKR and Vornado originally filed plans to get rid of Toys “R” Us in an IPO back in May 2010, but the markets turned soft and the offering never happened. Toys “R” Us withdrew its plans for an IPO in March.

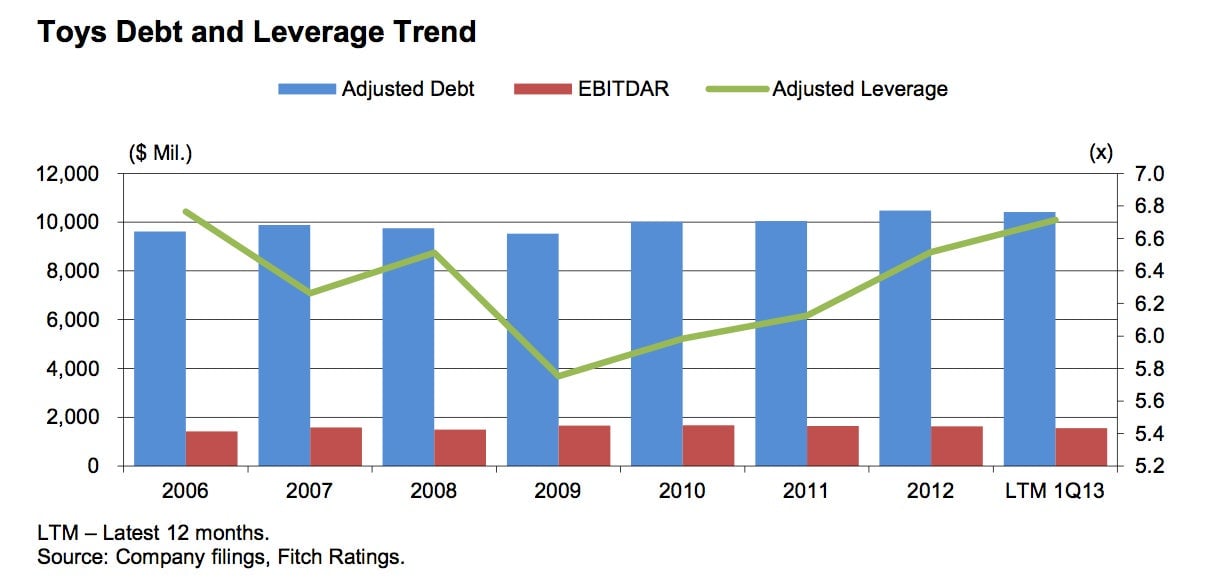

Meanwhile, the company has been slowly increasing its leverage since 2009. Here’s a chart of leverage—expressed as adjusted debt over a measure of operating earnings known as EBITDAR (EBITDAR stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization, and restructuring or rent costs)—from Fitch Ratings.

Such rising leverage leaves precious little room for operational error, which brings us back to the Christmas shopping season. The toy business is incredibly seasonal. More than 40% of Toys “R” Us sales come in the fourth quarter, and typically 70% of its operating profit, according to Fitch. Let’s just say that Toys “R” Us had better move a whole lot of Hug Me Elmos this year.