How Hong Kong’s “maid trade” is making life worse for domestic workers throughout Asia

Every few years, the city of Hong Kong is rocked by news that another foreign domestic worker has been badly abused by her employer. Last month, 23-year-old Erwiana Sulistyaningsih told authorities that she had been beaten daily, hit with mops, rulers, and clothes hangers until she could no longer walk.

Every few years, the city of Hong Kong is rocked by news that another foreign domestic worker has been badly abused by her employer. Last month, 23-year-old Erwiana Sulistyaningsih told authorities that she had been beaten daily, hit with mops, rulers, and clothes hangers until she could no longer walk.

But Hong Kong’s treatment of the thousands of women who are known here as “helpers” has ramifications beyond a case of physical abuse. The city’s double standard for foreign domestic wages and its increasingly strict policies are making conditions worse for hundreds of thousands of women across the entire region, where almost half of the world’s domestic workers are employed.

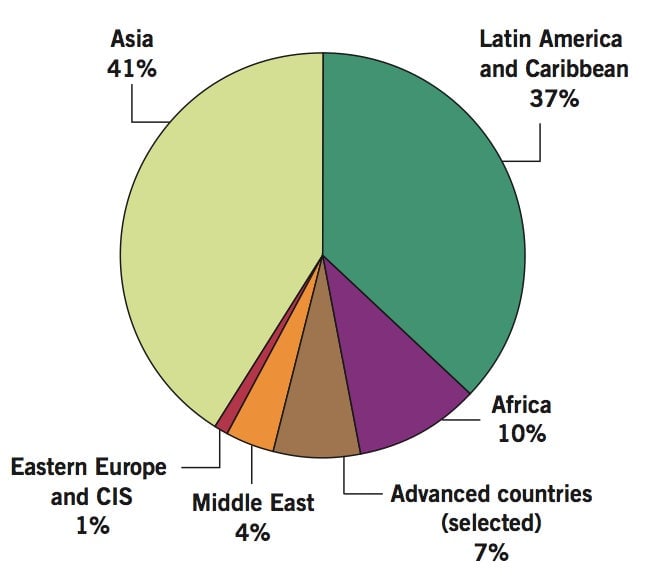

Globally there are 53 million domestic workers, mostly women, according to a conservative estimate by the International Labor Organization (ILO)—that’s an increase of almost 60% since the mid-1990s, and the ILO says the true figure may be closer to 100 million (pdf, p. 19). Some 41% of them are working in the Asia Pacific region, where keeping hired help has long been a tradition from the lower middle class to the wealthiest of families.

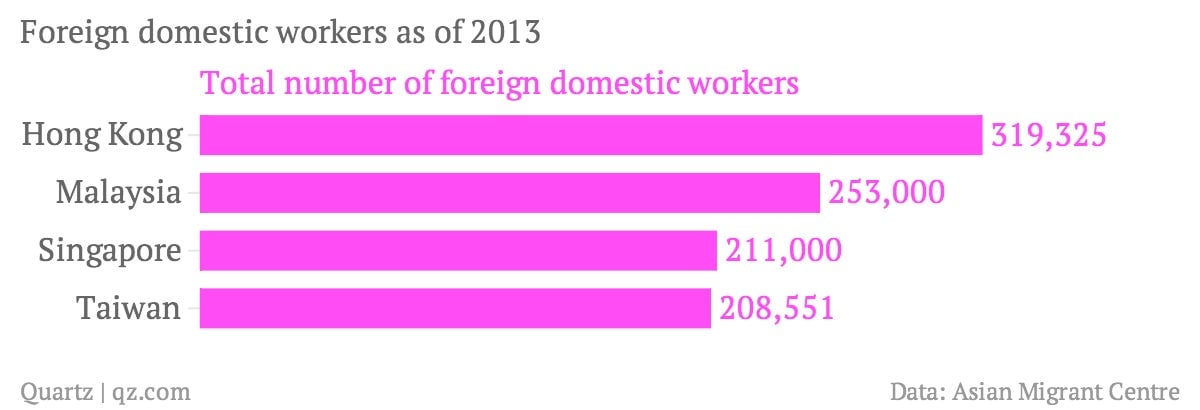

Domestic workers from poorer countries like the Philippines, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar pour into Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and Malaysia. This is Asia’s “maid trade,” a serpentine industry that involves hundreds of recruitment agencies, money lenders, debt collectors, and large government bureaucracies—not to mention about 21 million mostly uneducated women who work as housekeepers, nannies, and caretakers.

Hong Kong opened its doors to these maids and caretakers in the mid-1970s and now has one of the highest densities of domestic workers in the world. One in every eight households, and one in every three households with children, employs a housekeeper, usually a foreigner. These “helpers” make up about 10% of the working population, and 4.4% of the overall population.

The city has become a home away from home for many workers, in particular those from the Philippines—expats often refer to their housekeeper generically as “my Filipina”—and Indonesia. On Sundays, their day off, women toting blankets and cardboard crowd the city’s parks, underpasses, as well an open plaza at the bottom of HSBC’s Hong Kong headquarters. They share snacks and McDonald’s sundaes and play music on their phones. Some dance or play sports. “The people are kind here,” says Ann, 28, a domestic worker from Indonesia, sitting on a concrete ledge overlooking a basketball court at Victoria Park in central Hong Kong. She is wearing a sparkly light blue blouse, wedges and hazel-colored contact lenses—on her days off, she likes to dress up.

Overworked and underpaid

As one of the wealthiest locales in East Asia, Hong Kong has traditionally been the most sought-after destination for foreign domestic workers. It offers nominal protections such as paid annual leave, one day off a week, and legal channels through which to report complaints.

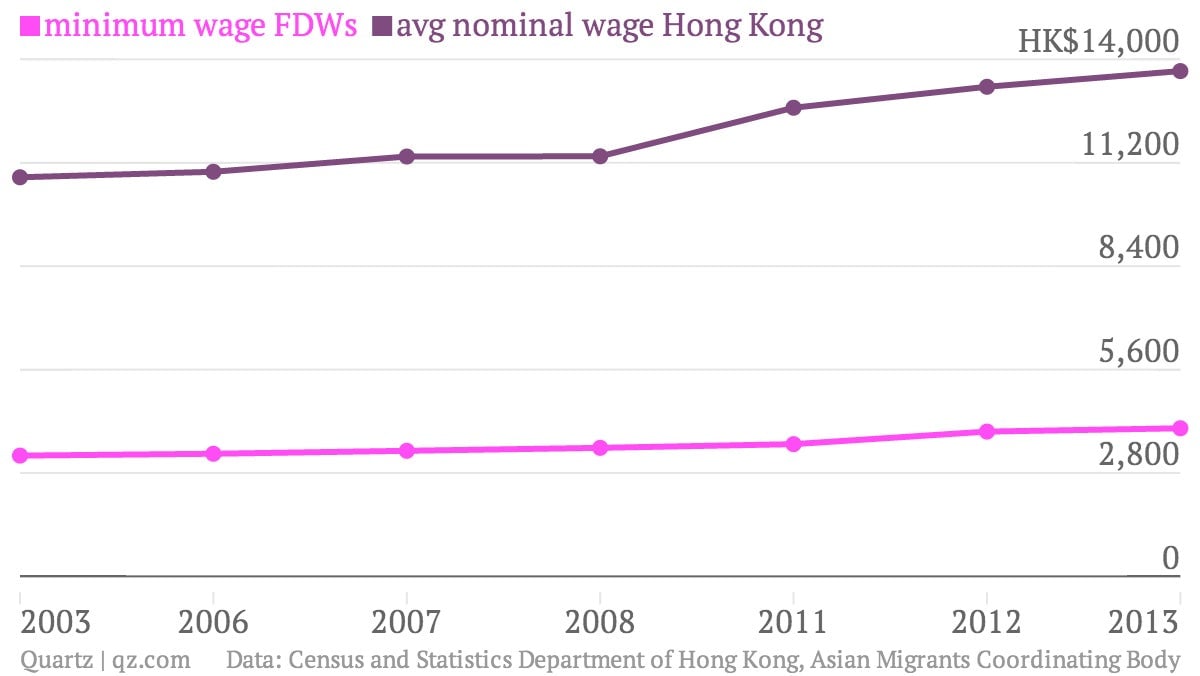

But for years the city has been keeping those wages artificially low with a two-tiered structure: HK$4,010 (US$515) a month for foreign domestic workers, and between HK$5,760 and HK$6,240 a month for everyone else, based on a 48-hour work week.

“The wage of the migrant domestic workers [in Hong Kong] has actually decreased,” said Fish Ip, managing direct of International Domestic Workers Federation. Taking into account inflation and the value of the Hong Kong dollar against other currencies, many foreign domestic workers are making less than they would have 16 years ago. Moreover, as Hong Kong’s median monthly income rose over 15% between 1998 and 2012, to HK$20,700 a month, the minimum wage for foreign domestic helpers has only risen 3.9%, or HK$150 (paywall).

Here’s how the minimum wage for foreign domestic workers (FDWs) has compared to average wages for workers in Hong Kong over the past decade:

Migrant domestic workers typically earn enough to send half of their salaries home—and that’s after the six months to a year they can spend paying off charges from recruitment and employment agencies. In Sulistyaningsih’s case, she owed about four months of wages to a recruitment agency.

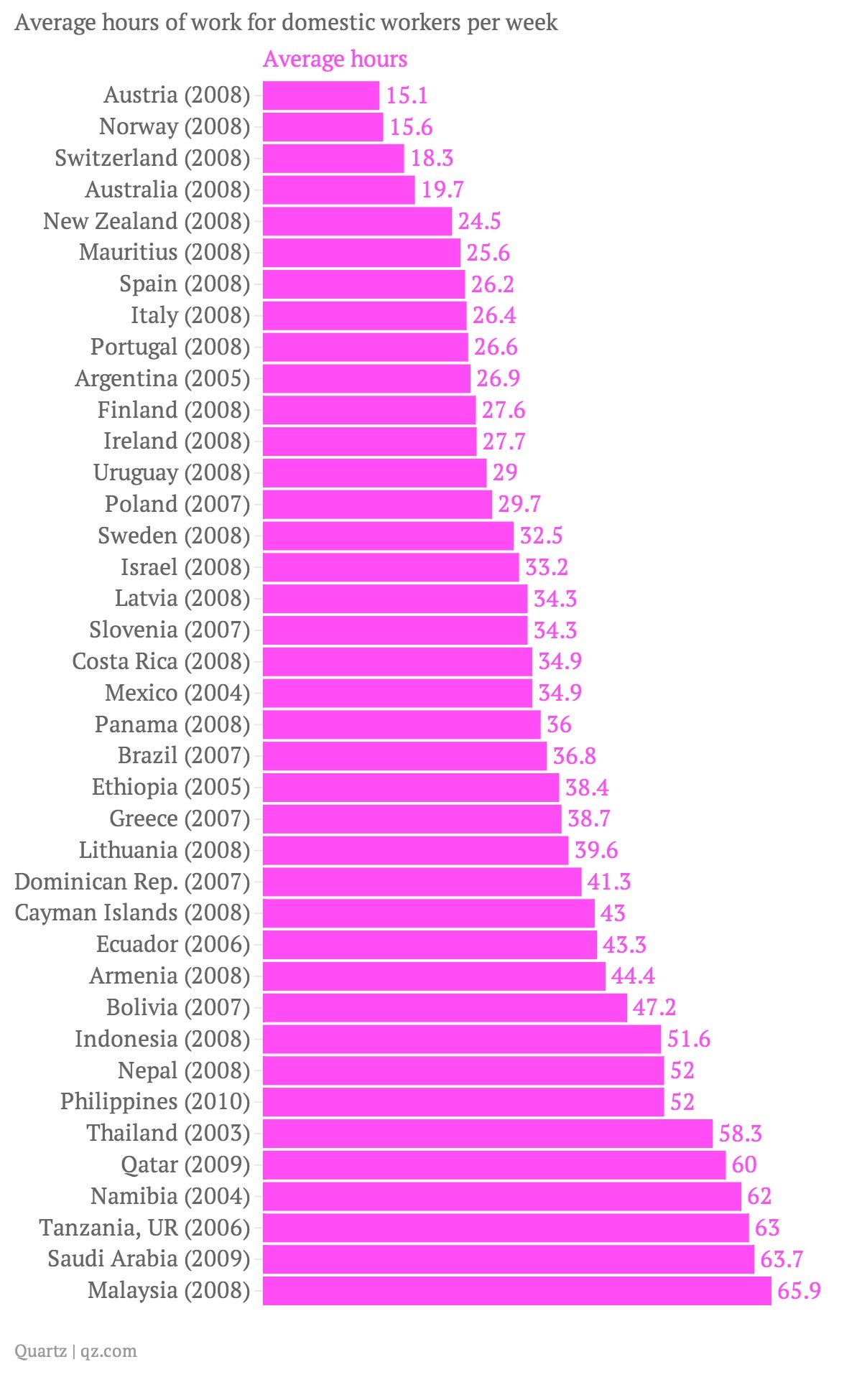

Hong Kong’s minimum wage for domestic workers also means little when there’s no limit on working hours. According to a report (pdf) by Amnesty International, a third of women surveyed said they worked 17 hours a day. Most only take one day off a week, which means many are working over 100 hours a week, making Hong Kong’s domestic workers some of the most overworked in the world. ”Objectively speaking, domestic workers are probably the most undervalued workers to work in Hong Kong,” says human rights lawyer Rob Connelly.

Low wages throughout Asia

Hong Kong’s low minimum wage also sets a low bar for other countries that recruit or send domestic workers, contributing to lower wages throughout the region.

In Taiwan, typical domestic worker wages are close to Hong Kong’s, or about NT$15,840 a month ($510). In Singapore, workers earn on average between S$400 and S$600 ($316-$475) a month. In Malaysia, where the cost of living is much lower than in Hong Kong, monthly pay for domestic workers is between 400 ringgit to 600 ringgit (between $121 and $181).

“An increase or decrease of foreign domestic worker wages in Hong Kong may impact wages for workers in some other destinations,” said Reiko Harima, managing director of the regional nonprofit Asian Migrant Centre. “Other countries may experience a shortage of foreign domestic workers if the wage is much higher in Hong Kong and the majority of workers prefer to migrate to Hong Kong, and [other countries] thus have to increase wage standards.”

Countries are also taking a cue from Hong Kong. Last year when Malaysia implemented a new minimum wage for all of the country’s workers, it followed Hong Kong’s model and excluded domestic helpers, the ILO has noted (pdf, p. 80).

“They do dirty jobs. That means they can be treated badly.”

Within Hong Kong, increasingly draconian policies in the city-state are exposing more migrant domestic workers to abuses like those suffered by Sulistyangsih. A local couple was arrested last year for burning their Indonesian maid with an iron and beating her with a bike chain. Earlier this month, a Hong Kong woman was arrested for hitting and pulling the hair of her Bangladeshi housekeeper.

This year, the government began implementing a rule that bars helpers from renewing their visas if they have changed employers more than three times in a year, a rule that’s meant to prevent “job hopping” but makes it more difficult to leave bad employers, said Sringatin, head of the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union. Ever since 2003, Hong Kong has required that foreign domestic workers live with their employers, a rule that exposes workers to unlimited working hours and gives them few avenues for escape if their employers become abusive.

Adwina Antonio, executive director of the Belthune House, a shelter for domestic workers, says that as of the third quarter of 2013, the shelter had dealt with 7,000 cases of alleged abuse, versus 3,000 for all of 2012. According to the Amnesty report, two-thirds of domestic workers interviewed said they had been physically or psychologically abused. Antonio recently encountered a woman who wasn’t allowed to bathe for two months.

“Migrant domestic workers are being treated as modern day slaves. They do dirty jobs. That means they can be treated badly. They are not treated as workers, they are treated as helpers,” Antonio said.

A not-so-endless supply

For years, Hong Kong has been accused of condoning modern-day slavery and treating helpers as second-class citizens, but the government’s fundamental approach hasn’t changed. “Basically, nothing has improved. The government has always been saying that there’s already enough protection,” says Luna Chan, chief operating officer of Pathfinders Hong Kong, a nonprofit that works on pregnancy and maternity issues for domestic workers.

That’s largely because there always seems to be a new group of helpers willing to accept the same or lower wages. Filipino women replaced Chinese domestic workers in the 1980s as the mainland economy took off. In the 1990s, Indonesian maids who would often work for half of what the minimum allowable wage was at the time became popular. Now, Indonesian and Filipino workers are becoming more educated about their rights, but newcomers from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Myanmar are starting to trickle into the city. The governments of these countries encourage the migration, which eases unemployment at home and provides a source of income via remittances.

And Hong Kong needs these domestic helpers as much as the workers themselves need the work. Foreign helpers have long been part of efforts to make up for a labor shortage by encouraging Hong Kong women to enter the workforce. Female employment has grown to 54.7% as of 2013, from 47.5% in 1982. Foreign helpers contribute as much as $13.3 billion a year, or 5% of Hong Kong’s 2012 GDP, by giving middle class families the ability to have both parents working, according estimates by the nonprofit HK Helpers Campaign. They also provide a welfare service that the government doesn’t: taking care of Hong Kong’s expanding population of elderly residents.

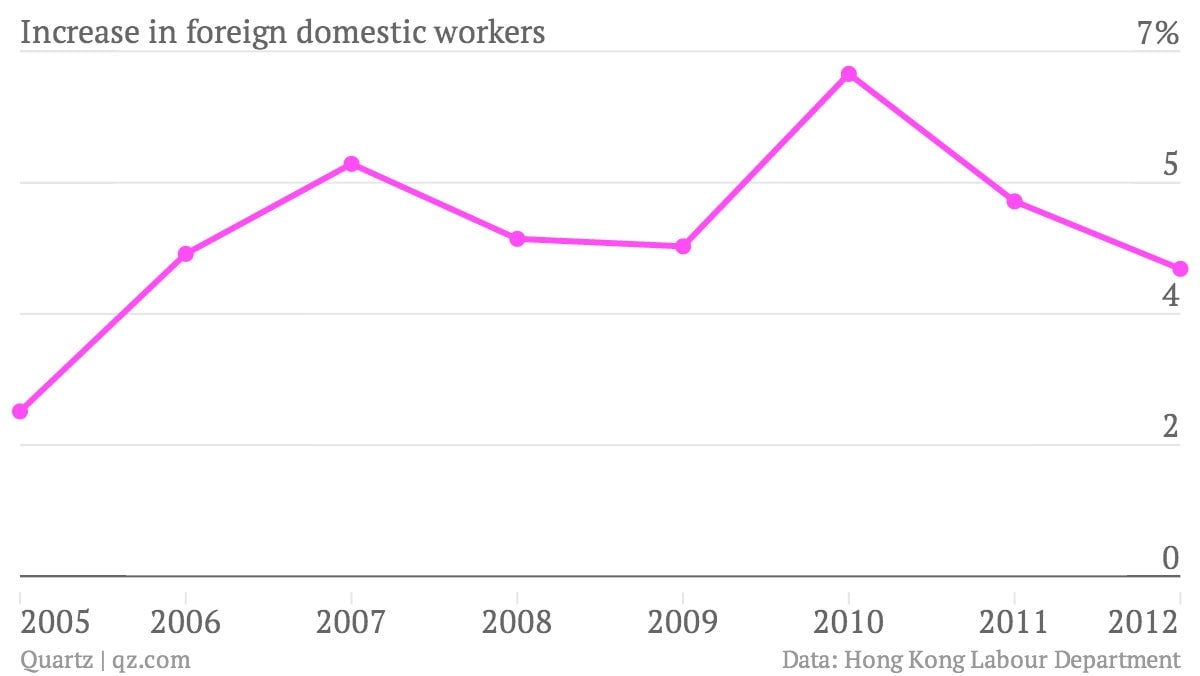

The supply of foreign domestic workers might not always be endless. Countries are starting to react to increasing cases of abuse: Indonesia has pledged to stop exporting its domestic workers by 2017. The employment agency in Myanmar responsible for sending domestic helpers has pledged to be more vigilant about standards, and is in talks with the ILO about better practices. Year-over-year increases of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong have started to trail off—perhaps pointing to a day when the global supply of housekeeper labor will tighten enough that Hong Kongers will have no choice but to pay their domestic staff a better wage.