There’s a nasty little worm eating France’s escargots

French snails, take cover. A team of local scientists have confirmed what could be the escargot industry’s worst fears. Platydemus manokwari, a snail-eating flatworm, has arrived in France.

French snails, take cover. A team of local scientists have confirmed what could be the escargot industry’s worst fears. Platydemus manokwari, a snail-eating flatworm, has arrived in France.

This is what it looks like:

This is what it does to snails:

While the threat to France has yet to be assessed, there’s good reason to be believe it could be devastating. The highly efficient predatory worm, also known as the New Guinea flatworm, is listed among the world’s 100 most invasive species. And for good reason: It’s a leading cause of snail population decay and even flat-out extinction in the 15+ countries and habitats it has traversed. Take Hawaii, for instance, where the presence of the worm has driven an estimated 90% of the US state’s 750 species of land snails extinct, according to the Invasive Species Specialist Group.

“This species is extraordinarily invasive,” Jean-Lou Justine, a professor at the National Museum of Natural History, told Agence France-Presse. ”All snails in Europe could be wiped out. It may seem ironic, but it’s worth pointing out the effect that this will have on French cooking.” The French consume some 30,000 tonnes (33,000 tons) of snails each year. With fewer and fewer of those being produced locally, an onslaught on the country’s snail population could do away with “true French” escargot altogether.

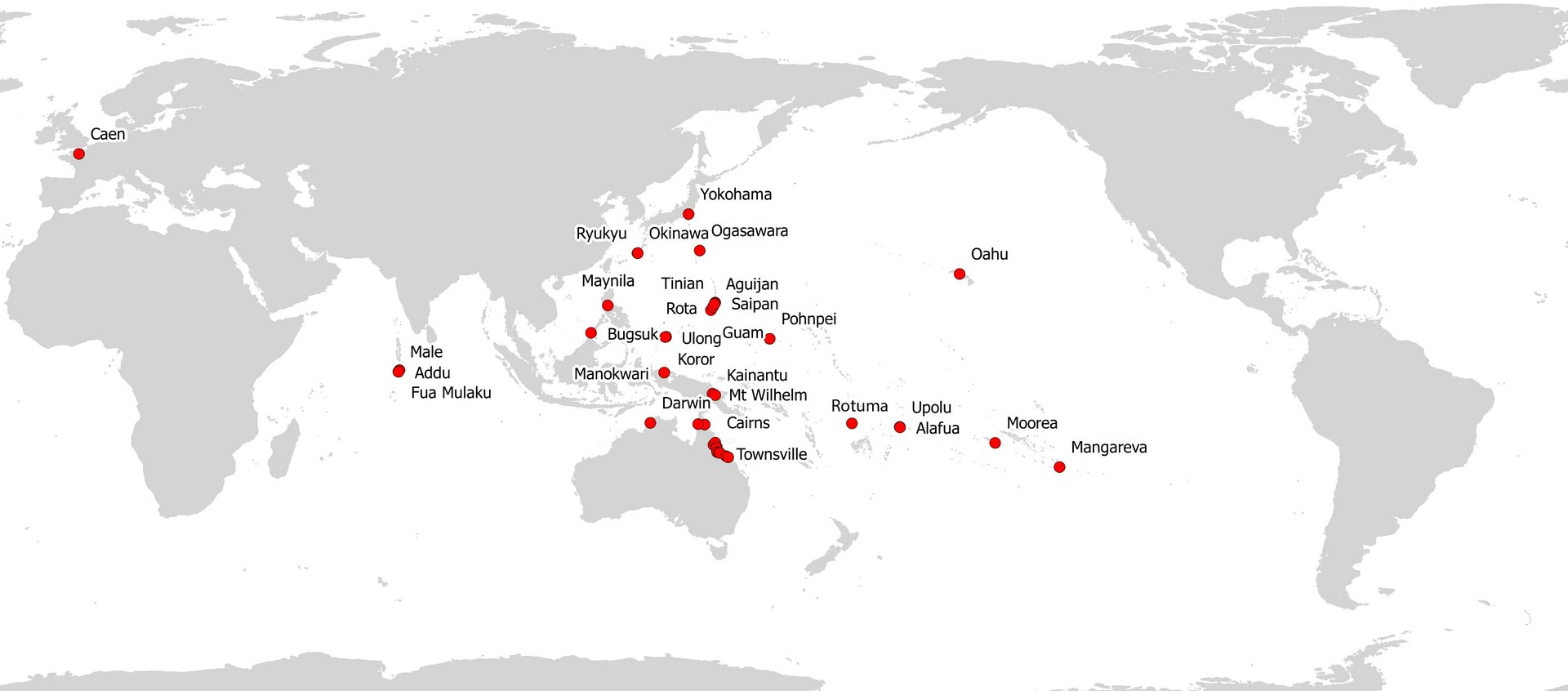

The New Guinea flatworm’s appearance in France also heralds an alarming spread into the West. Until now, it had only been found in the Indo-Pacific region. Here’s the map the group of scientists shared:

It’s yet unclear how the flatworm made its way to Europe—strict agricultural import restrictions have been in place for years to curb its spread. But if it’s in France, it may be roaming elsewhere in Europe, too. Which is a scary thought, considering that there are currently no known chemical or biological methods for controlling the pests. The only consensus way to kill it, thus far, has been temperatures below 10°C (50°F). France may want to pray for a bit of the US’s polar vortex.