Your reality is 15 seconds in the making

When you really focus your attention on something, you’re said to be “in the present moment.” But a new piece of research suggests that the “present moment” is actually a chunk of the recent past, and it’s about 15 seconds long.

When you really focus your attention on something, you’re said to be “in the present moment.” But a new piece of research suggests that the “present moment” is actually a chunk of the recent past, and it’s about 15 seconds long.

Jason Fischer of the University of California at Berkeley, the lead author of the study (paywall), said he wanted to know how our perception changes as we shift our attention from one thing to another. For example, how does your brain process the motion of the annoying housefly buzzing around your kitchen, as opposed to its companion you’ll be swatting next?

His research, published with his co-author David Whitney, suggests that when we focus on something, the image we perceive isn’t a snapshot of it at that moment, but rather a sort of composite—a product mostly of what we’re seeing now, but also influenced by what we’ve been seeing for the previous 15 seconds or so. They call this ephemeral boundary the “continuity field”, and it could explain a lot about how we pay attention.

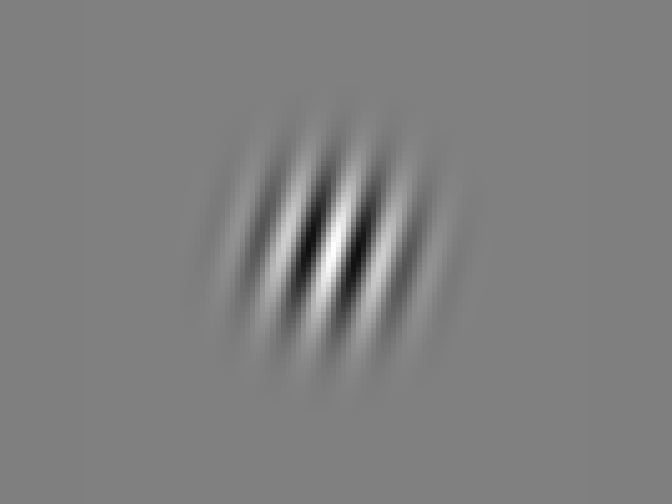

Fischer and Whitney devised a battery of experiments that showed them how our brains build miniature narratives for the objects of our attention. Subjects were shown flashes of lines called Gabor patches, one every five seconds, on a computer screen. Immediately afterward, the subjects were asked to use the arrow keys to recreate the direction the Gabor patches were tilted in.

It’s no surprise that the image people saw most recently was the one they were most likely to remember. However, they tended to make slight errors in the angle of the lines, which were influenced by the previous three images, each to a lessening degree. For example, if the last image they saw was tilted 45 degrees to the right, but the three before it had been tilted to the left, the subject would perceive the rightward tilt to be less than 45 degrees. This suggested that when our eyes record the present moment, our brain perceives a smearing of recent activity rather than a frozen frame of time.

It would be a mistake to read too much into so narrow an experiment, and one performed on only 12 subjects (albeit for several hours each). But according to Fischer, though, this aspect of perception has not been studied much, and his research is a step in that direction.

So if these ”continuity fields” are real, what purpose do they serve? Fischer suggests that they might play a part in enabling us to focus attention on some things but not others. If it weren’t for your ability to pay selective attention, you would be a slave to every detail—for example, imagine trying to drive in a rainstorm if you were constantly tracking every droplet coming down the windshield.

Fischer says he would like to expand the trials—including tests on other senses, like hearing—and it wouldn’t be too hard to introduce a version of the test online so they could easily recruit more subjects. He thinks the research could help understand autism and attention-deficit disorders.