Childbirth death is way more likely in the US than the UK, and it’s getting worse

The US is one of only eight countries to see an increase in childbirth-related deaths since 2003, according to a study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington. While maternal mortality has dropped by 3.1% in developed countries (and 1.3% globally) since 1990, it increased by 1.7% in the US during the same time period.

The US is one of only eight countries to see an increase in childbirth-related deaths since 2003, according to a study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington. While maternal mortality has dropped by 3.1% in developed countries (and 1.3% globally) since 1990, it increased by 1.7% in the US during the same time period.

More than 18 mothers died for every 100,000 live births in the US in 2013, which is more than double the rates in Saudi Arabia and Canada, and more than triple that in the UK. The biggest increase occurred in women aged 20-24: While only 7.2 women died for every 100,000 births in 1990, that age group saw a mortality rate of 14 per 100,000 in 2013. Now the US is ranked at 60 out of 180 countries in the measures of maternal death (where a lower number indicates fewer deaths). This is down from a rank of 50th based on the last available data (from 2004-2008), and a rank of 22nd in 1990.

Dr. Nicholas Kassebaum, an assistant professor at IHME, said in a statement that it’s unclear why this is happening. Lack of access to prenatal care, an increase in Caesarean sections, and complications related to obesity and diabetes could be factors. “The good news,” Kassebaum said in a press release,”Is that most maternal deaths are preventable, and we can do better.”

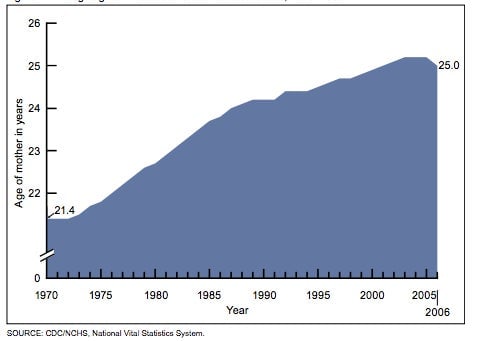

But unfortunately, fixing this can be pretty complicated because it requires addressing large intractable problems or changing societal trends: Women without insurance are more likely to suffer complications after childbirth, for example, probably because they’re not given enough prenatal and antenatal care. And even among insured women, the age of first childbirth has gone up—which increases risks, as older mothers are more susceptible to complications.

Those with private insurance are also more likely to have Caesarean sections, according to a 2013 study led by Katy Kozhimannil, an assistant professor of public health at the University of Minnesota. The rate of Caesareans in the US, which at 30% is more than double the rate recommended by the World Health Organization, exposes mothers to increased risks of infection and blood clots.

So while a lack of prenatal care for the uninsured is certainly an issue—and one that will hopefully be addressed by the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act—the US may need to address risk factors for insured mothers, as well.