If you care about equal pay for women, tennis is the sport for you

Players in this year’s World Cup might be diverse when it comes to nationality, but there is something all the soccer players have in common: Each and every one is male. At Wimbledon, however, male and female tennis players are given equal screen time and equal pay.

Players in this year’s World Cup might be diverse when it comes to nationality, but there is something all the soccer players have in common: Each and every one is male. At Wimbledon, however, male and female tennis players are given equal screen time and equal pay.

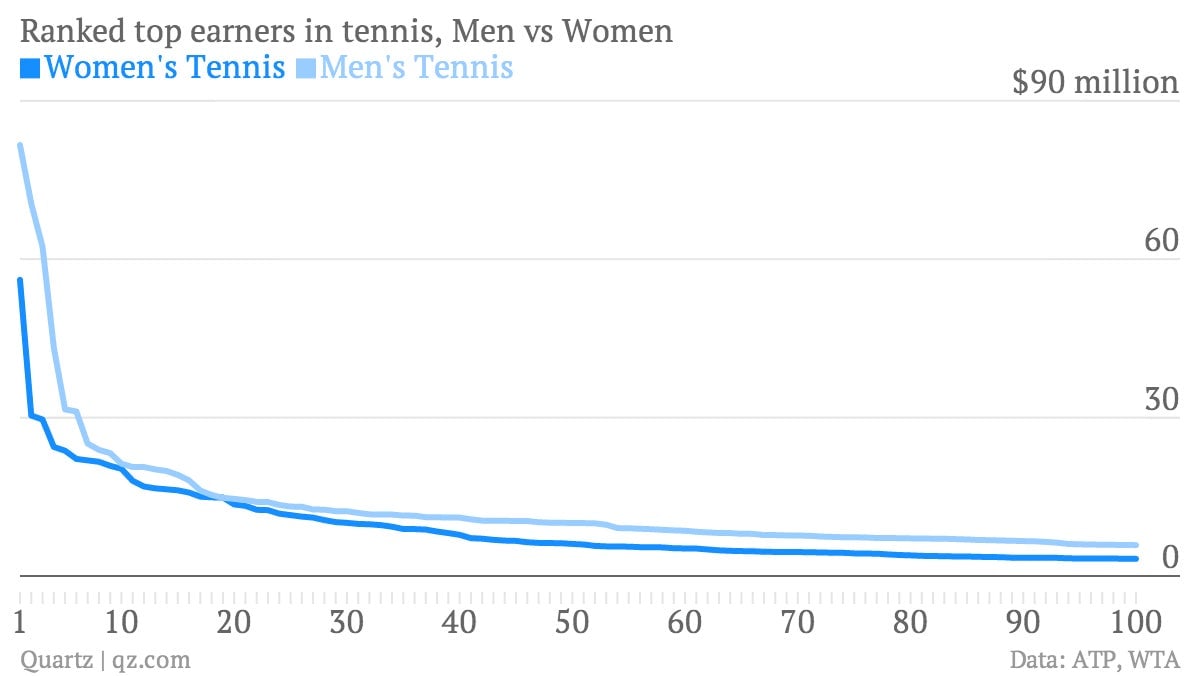

Indeed, tennis is the only sport where female athletes can hope to be paid anything close to what the men get:

Only three women appear on Forbes’ list of the 100 highest-paid athletes—including both endorsements and pay—and all of them are tennis players. The same number of male tennis stars is on the list, so it’s not as if tennis is simply a more lucrative sport. Though all three men’s players are higher on the list than the women, top female players can make serious cash by winning at tennis. Serena Williams amassed $11 million in tournament winnings over the year to June, well over the $6.2 million Tiger Woods earned from prizes in golf.

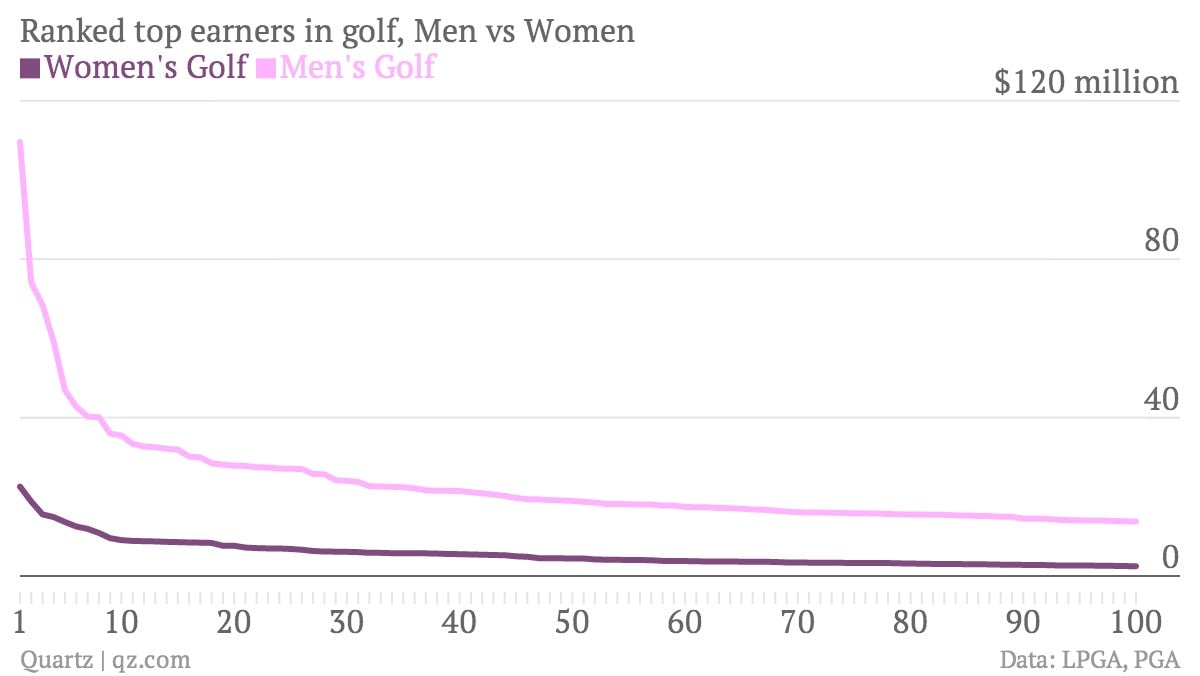

Golf is actually an interesting comparison, because it’s the only other sport where the top-100 women earn a salary that allows them to be full-time professional athletes. Even so, the male/female earnings discrepancy is far greater in golf than in tennis. This is the gap in earnings between the most successful men and women golfers:

The golf gap is big, but it’s still much smaller than in other sports. Earlier this year, BuzzFeed compiled a list of the 52 National Basketball Association stars whose salaries, without endorsements, are larger than the total pay given to all professional women basketball players in the WNBA. In Major League Soccer (MLS), the American men’s league, players regularly earn annual salaries in the six figures, as the official salary list (pdf) shows. Meanwhile, the National Women’s Soccer League in the US pays its players salaries ranging from $6,000 to $30,000.

To be sure, history’s most successful men’s tennis players eclipse the best of the women in terms of earnings. Roger Federer tops the all-time list, having won $82 million from tournaments. By comparison Serena Williams, the top woman, has made $56 million. But in the middle ranks of the sport, the numbers aren’t all that different. Martina Hingis’s $20.3 million puts her 10th on the women’s list, compared to $20.6 million for Andy Roddick, who is the 11th most successful male player and was active around the same time as Hingis.

The popularity of women’s tennis means players can win also bigger endorsements than in other sports:

All kinds of reasons are given to explain why tennis is by far the most popular women’s sport. There is the “women’s tennis is different from men’s but equally interesting” argument. There is the more cynical “short skirts sell tickets” argument.

Here’s another thesis: Much of the relative equality is due to the largest tournaments in tennis paying the same winnings to men and women, and treating both equally. Women have participated in Wimbledon since 1880, and yet for years, London’s stodgy Wimbledon resisted this policy—implemented long ago by the US Open and Australian Open. It too came around in 2007.

Men and women play the biggest tennis tournaments simultaneously, and are given the same amount of attention by broadcasters and organizers. Today, just as many women’s matches are televised as men’s. Women play on the main courts, just as men do. At the Wimbledon opening yesterday, the women’s number two, Li Na, played her match on Centre Court before the top men’s player, Novak Djokovic. Li was given precedence over Grigor Dmitrov—one of the most exciting new players in the men’s game—who was relegated to the less prestigious Court 1.

This has two effects. First, it builds on the interest in a sport that comes during any major competition. A women’s soccer cup that happened in conjunction with the World Cup would be watched because people would be hungry for opportunities to watch soccer and support their national teams. Second, it means viewers associate a sport with women and men alike. Watching a Grand Slam isn’t about men’s tennis or women’s tennis: It’s just tennis. World Cup soccer is always men’s soccer.

All of that creates a significant base of engaged women’s tennis fans, giving players enough exposure to attract major endorsements. This, along with pay equality at big tournaments, makes a career in tennis a lucrative prospect for promising young girls. The parents of a female soccer prodigy would want their daughter to use her talents as part of a healthy hobby, nothing more. In tennis, however, becoming the next Hingis or Williams means not just sporting excellence, but big cash prizes. The extra incentive leads to better women’s tennis infrastructure and higher-quality players.

This might look like a tautology—popularity makes tennis lucrative for women, which makes it more popular—but it’s actually a virtuous circle that begins when men and women play side-by-side in a single tournament. Leveraging the popularity of a big sporting event builds enthusiasm for the women’s game. That increases the potential rewards from endorsements, leading to more interest, higher-quality players, better viewing, and even greater popularity. And so on.

There is no perfect equality here. Outside of the Grand Slams, women’s tournaments don’t pay nearly as much as the men’s. And while the example of tennis makes it seem like it would be a great idea for soccer and all other gender-imbalanced sports, it’s hard to imagine a female soccer World Cup being played alongside the men’s anytime soon. Even less likely would be the soccer equivalent of mixed doubles, in which men and women play on the same field.

Until that comes to pass, if you’re getting sick of the testosterone-filled World Cup, you might be refreshed by a flip over to Wimbledon.