Here is the recipe for perfectly browned pizza cheese as established by science

You need to make a pizza that achieves the perfect level of browning and melts as smoothly as a typical pie made with mozzarella, but you want to kick up the flavor with some gourmet cheeses. It’s a very serious conundrum. And now there’s scientific research that can help you with it.

You need to make a pizza that achieves the perfect level of browning and melts as smoothly as a typical pie made with mozzarella, but you want to kick up the flavor with some gourmet cheeses. It’s a very serious conundrum. And now there’s scientific research that can help you with it.

Researchers at the University of Auckland (in partnership with Fonterra, the world’s largest dairy products exporter) used a machine to measure the integral elements of possible pizza ingredients as precisely as possible, and then published a paper about it in the Journal of Food Science. Naturally, it was entitled “Quantification of Pizza Baking Properties of Different Cheeses, and Their Correlation with Cheese Functionality.”

What is “cheese functionality,” you ask? It’s a series of properties, including “rheology [i.e., how a substance flows], free oil, transition temperature [between “elastic” and “viscous” states], and water activity.” The aim of the study was to test the correlation between these properties and the “browning and blistering” abilities of different cheeses on a pizza. In addition to mozzarella (of course), they tested cheddar, colby, edam, emmental, gruyere, and provolone.

The researchers baked the pizzas, then placed them in a light-box system that used computerized image analysis to evaluate things like color, uniformity, and browning attributes. As the paper explains, this approach was a groundbreaking innovation in pizza research:

An image analysis method based on machine vision has been developed to quantify the color and color uniformity of nonhomogeneously colored agricultural materials, which has been applied to rabbit meat and banana samples (Balaban 2008). However, this image analysis method has not been applied to baked cheese.

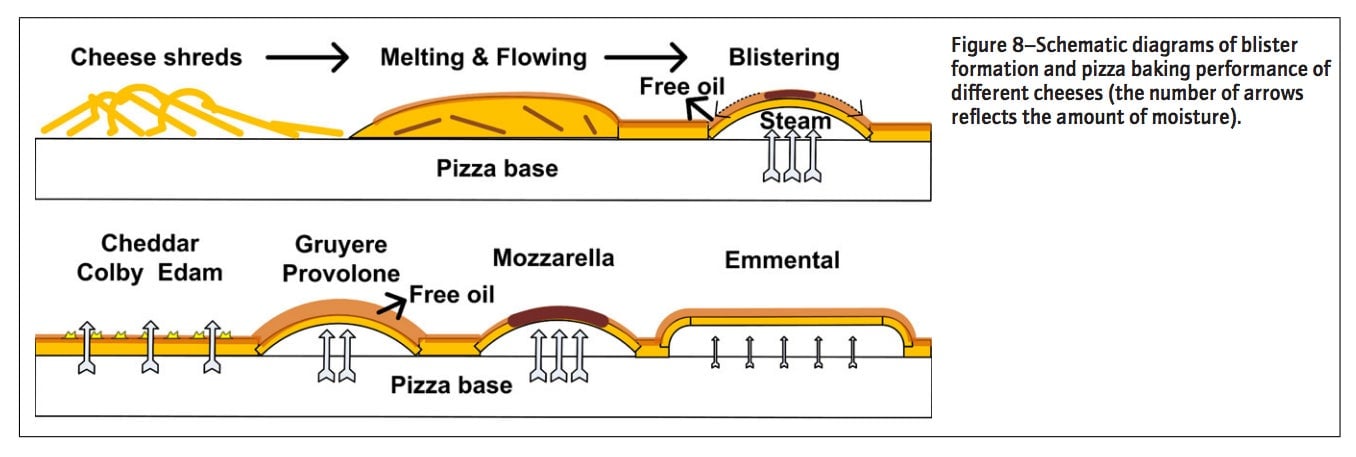

So what happens to cheese when you bake it? This.

For cheese to brown, the paper explains, it needs to lose moisture first. For the moisture to evaporate, blisters need to form, because where they lift the surface of the cheese, free oil can run off and expose the surface to raw heat. And for a blister to form, steam needs to collect in a pocket and push up the cheese.

In a video about the research, Bryony James, associate dean of chemicals and materials engineering at the University of Auckland, explains:

“You can imagine that as a blister forms, if there’s lots of free oil, that it might never break free of the oil layer and brown. But if it’s not got that much free oil, the oil can flow off, leave the top exposed and so you get this discreet patch of browning.”

This is why mozzarella makes for good browning. First, it doesn’t have much free oil. Second, it is very elastic. Third, it contains a lot of moisture. So steam pockets form easily, which create healthy blisters, which quickly expose the surface to browning.

By contrast, cheddar, colby, and edam have a relative lack of elasticity, which makes them no match for the steam forces, meaning that “gas bubbles of these cheeses burst at an early stage of the formation of blisters.” No blisters, no browning.

So if you want to make a perfect-looking pizza with a special flavor kick, here is the recipe, with the imprimatur of science:

Different cheeses can be employed on “gourmet” pizzas in combination with Mozzarella. Gruyere and Provolone can be added to obtain less burnt appearance by producing more free oil, and the color would be more uniform by adding cheeses with low elasticity, such as Colby.