People in the West can stop obsessing about learning Chinese

The leaders of the Western world think their young citizens should be learning Mandarin Chinese. David Cameron said so late last year. And Barack Obama’s own daughter, Sasha, is learning the language.

The leaders of the Western world think their young citizens should be learning Mandarin Chinese. David Cameron said so late last year. And Barack Obama’s own daughter, Sasha, is learning the language.

Why Mandarin? The arguments are familiar: First, China’s growing economic heft. “By the time the children born today leave school, China is set to be the world’s largest economy,” Cameron said. “So it’s time to look beyond the traditional focus on French and German and get many more children learning Mandarin.”

The second reason is that Chinese gives a speaker access to the world’s largest linguistic population. Why learn Spanish, with a measly 400 million speakers, when China is home to 1.3 billion?

But that second argument assumes that everybody in China is fluent in Mandarin. They’re not. The country’s official education ministry announced last week (link in Chinese) that only 70% of people in the country can be considered Mandarin speakers. Of that 70%, the ministry said, “only 10% are capable of communicating fluently” in the language. In short, you don’t have to be fluent in Mandarin to speak better than 93% of China.

As this interactive map shows, there are vast linguistic differences within China, despite the official language being Mandarin. Even within Mandarin, there are several dialects that share the same writing system. The version referred to as “Putonghua” or “common speech” in Chinese is just one of many ways of pronouncing these characters. The current standard form is based on the Beijing dialect, as Chinese law states explicitly, but as late as the 19th century, the Nanjing dialect was considered more universal.

If we assume most of the Taiwanese population to be fluent in Mandarin, and generously account for the Chinese diaspora abroad, the number of fluent speakers worldwide looks more like 120 million. That number is comparable if not lower than the number of fluent speakers of Asian languages like Hindi, Urdu, or Bahasa Indonesian. And it’s also far smaller than the aforementioned 400 million Spanish speakers. But this hasn’t stopped Mandarin from taking precedence over these languages in the minds of politicians, parents, and language schools offering it as the up-and-coming language of international business.

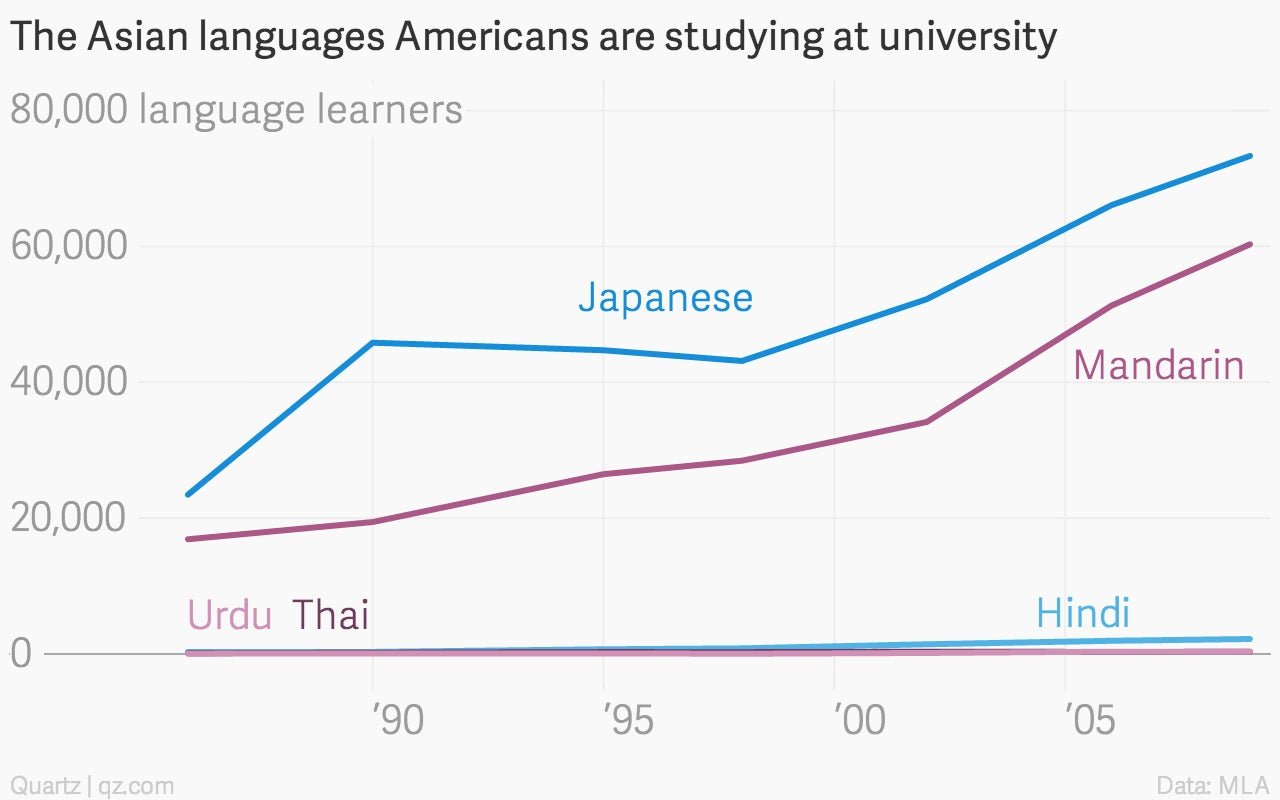

The Modern Language Association of America (MLA) conducts regular surveys of language enrollment at universities in the US. The most recent survey, taken in 2009, shows Mandarin catching up to Japanese and positively dwarfing its regional counterparts.

No doubt this trend is even more exaggerated today. At the bottom of that chart are other economically and geopolitically important languages with hardly any American interest. The MLA counted 2,200 Hindi learners, compared to over 60,000 for Mandarin. Urdu and Thai are barely visible, with learners in the hundreds.

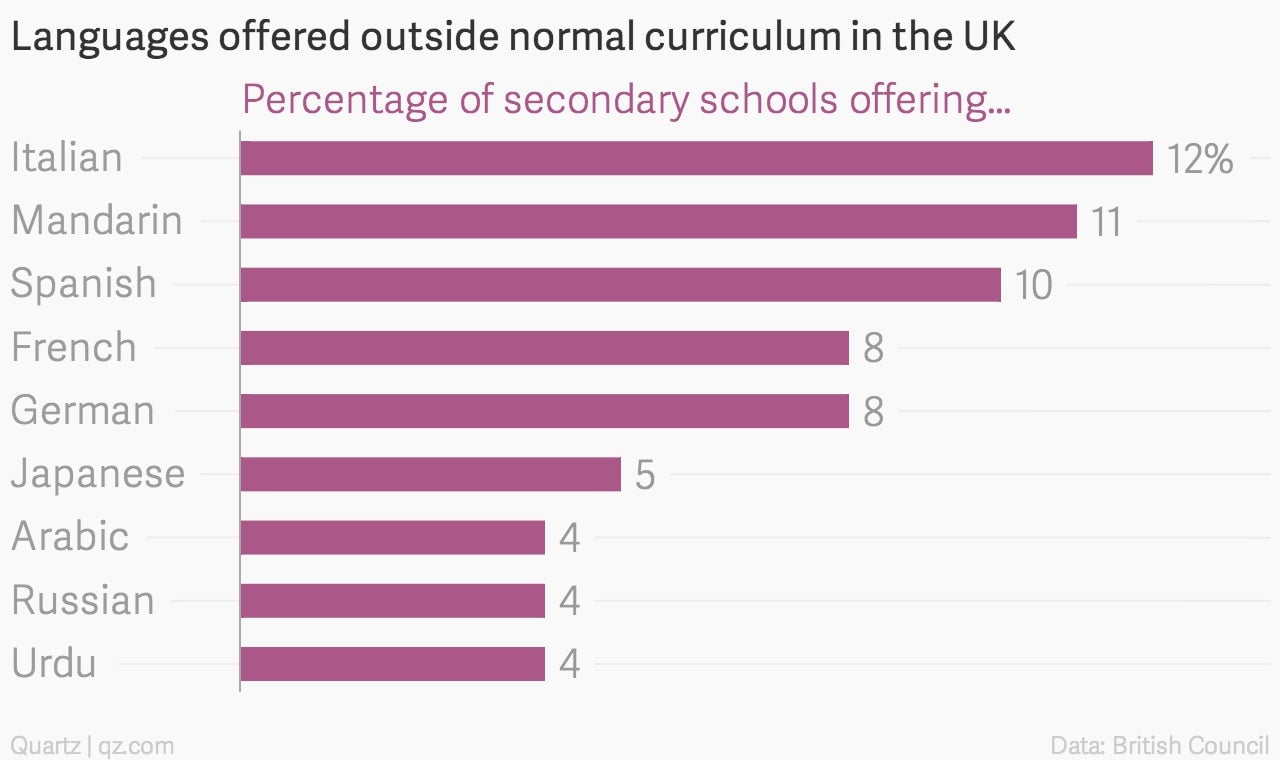

The trend extends beyond American universities. A British Council survey (PDF) of secondary schools in the UK shows that people elsewhere in the West are increasingly concerning themselves with Mandarin instruction. The numbers are still small for classes taken as part of the UK’s national curriculum, but Mandarin is number two on the list of languages schools offer outside of it.

China’s economy is as good a reason as any to learn its language. But even if (or when) China does overtake the US as the world’s largest economy, the difficulty foreigners have learning Mandarin and its written script makes the language unlikely to challenge the dominance of English in international trade. (Indeed, even during Japan’s dramatic post-war economic expansion, Japanese never came close to toppling English as the global lingua franca.) Besides, China isn’t the only Asian country with good growth prospects—and anyway its fastest-growth days are probably behind it.

So if you’re looking to learn an Asian language, your country and your job prospects may well benefit from a non-Mandarin option. The same goes for your kids. You might even choose Cantonese, which by some measures has around 60 million speakers, many of whom live in economically important coastal Chinese cities.