When American psychologists use their skills for torture

At 11am on July 2, my friend and colleague, Steven Reisner, and I met with the board of the American Psychological Association (APA). The board had just received a devastating report on an investigation of the APA’s years-long collusion with the CIA and US defense department in support of psychologist involvement in the George W. Bush-era torture program.

At 11am on July 2, my friend and colleague, Steven Reisner, and I met with the board of the American Psychological Association (APA). The board had just received a devastating report on an investigation of the APA’s years-long collusion with the CIA and US defense department in support of psychologist involvement in the George W. Bush-era torture program.

The board had commissioned the investigation by Chicago attorney David Hoffman and his team last November in response to allegations by New York Times reporter James Risen’s book, Pay Any Price: Greed, Power, and Endless War. Reisner and I have been prominent critics over the last decade of the APA’s stance on these issues. We were also the lead psychologist authors of an April report, also featured in the Times, that alleged similar APA collusion. Because of our expertise on the issue, the board wanted to know our recommendations (pdf) for how they should deal with the Hoffman Report’s disturbing conclusions.

The new report documents, in over 542 pages, the extent to which APA officials cooperated with the government to re-interpret the association’s ethics code. Their aim? To enable military psychologists who participated in sometimes torturous interrogations, including those at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba and Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. The APA simultaneously kicked off a public relations campaign in order to falsely claim that it was trying to protect human rights and detainee welfare. Anti-torture resolutions passed by the APA during this period, according to the Hoffman Report, were often “pre-cleared” by government officials.

Further, and in a particularly perverse move, APA leaders repeatedly called on those with information about abuses—perpetuated by individual psychologists during detainee interrogations—to file ethics charges with the APA ethics office. When complaints were filed, however, they were rarely if ever investigated.

When the public thinks of psychologists, many think of psychotherapists and others who devote their careers to improving people’s lives. Others may think of professors and researchers studying how the mind works. Like other health professionals, psychologists are supposed to be guided by the ethical injunction to “do no harm.” Public belief that psychologists take this injunction seriously is vital to the trust required for successful mental health treatment. However, investigations by congressional committees, governmental agencies, and numerous press reports over the past decade have made it clear that some CIA and military psychologists used their knowledge and expertise to break people down, impervious to the harm caused.

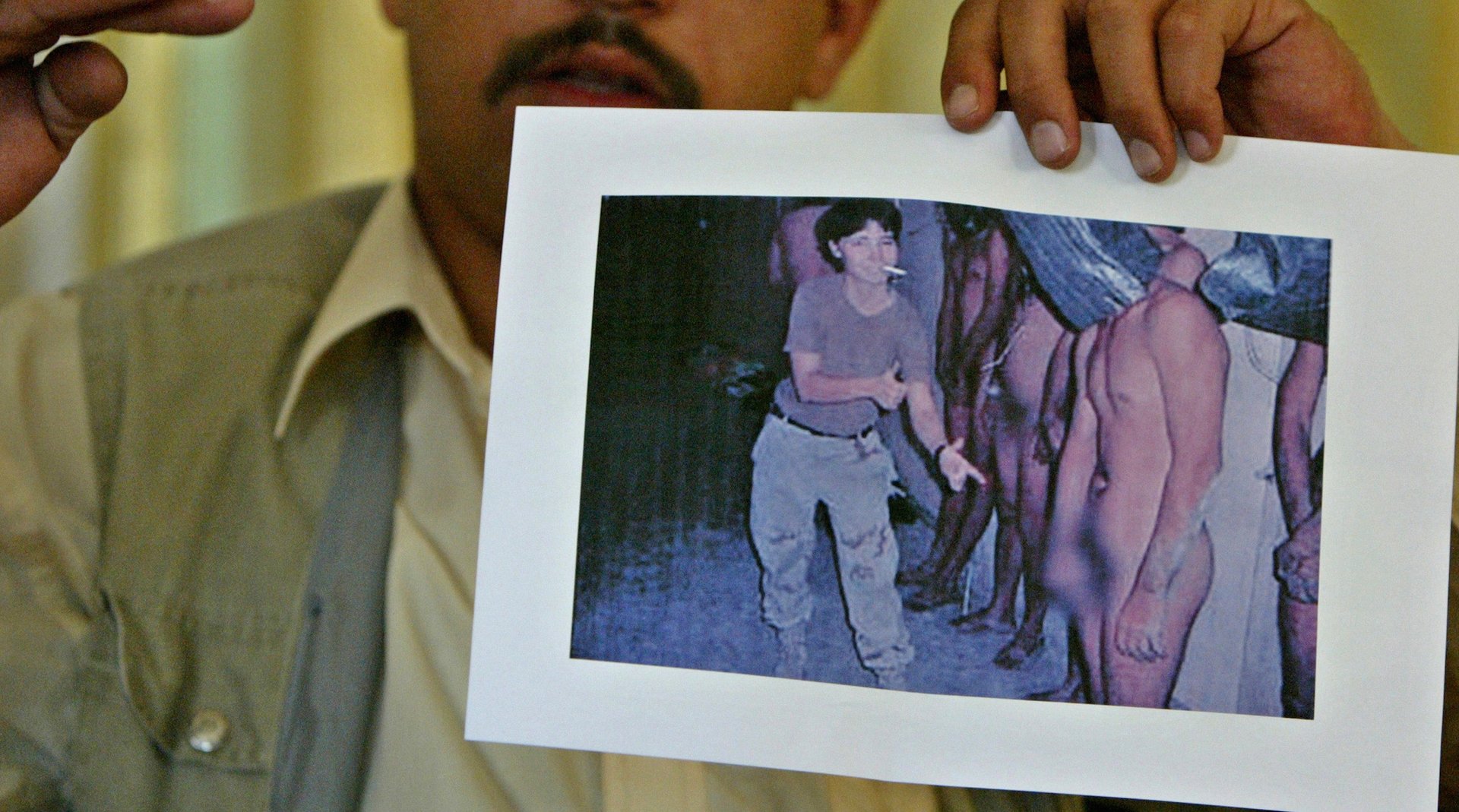

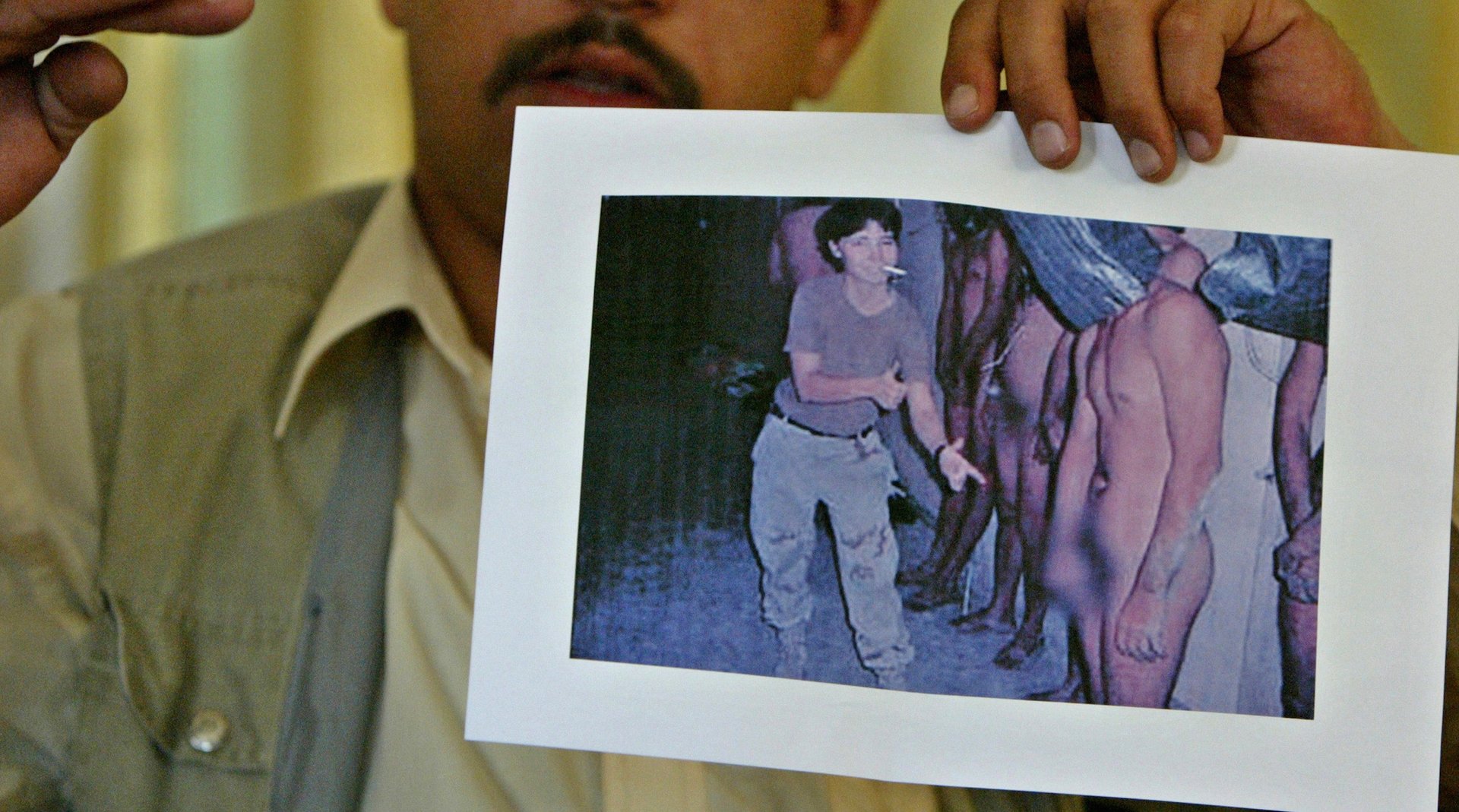

Release of the Senate Intelligence Committee torture report last December provided chilling details on the methods used to accomplish this. The Senate report described how two psychologists under CIA contract utilized the psychological theory of “learned helplessness” to justify treating detainees as little better than dogs. Detainees were subjected to isolation in total darkness for weeks on end, days of painfully imposed sleep deprivation, forced nudity, “rectal hydration,” prolonged extremes of hot or cold, and the interrupted drowning technique referred to as “waterboarding.”

The psychologists’ theory was that when detainees were shown that nothing they did would alleviate the unremitting misery—that they were in fact helpless—they would become cooperative. The Senate report documents the tragic silliness of this idea, as such techniques merely made hapless detainees tell the interrogators whatever they thought the interrogators wanted to hear, true or not.

Similarly, though possibly not quite as extreme, were the abuses that occurred to detainees in military custody in Guantánamo and various prisons in Iraq and Afghanistan, as documented by the Senate armed Services Committee in 2009. As in CIA prisons, abuses at Guantánamo were aided by psychologists.

In addition to their role as interrogation advisors, psychologists, and other health professionals, played another essential function in the Bush era torture program. In a crystal clear twisting of their professional and ethical duties, such experts served as critical “get out of jail free cards” for those conducting and authorizing the abuses, as was articulated in the justice department’s “torture memos.” The basic logic was that torture, in the US interpretation, required severe, long-lasting harm. So, if a health professional could testify that applying certain techniques wouldn’t cause that level of harm, no one could be prosecuted, whatever the result.

Thus, CIA and defense department protocols required the presence of health professionals, often psychologists, to make these assurances as the abuse proceeded. Those health professionals, in turn, wanted to make sure that their participation would not lead to professional sanctions or other professional consequences. And that’s where the APA came in.

For years, critics inside and outside the APA called upon its constituents to stop participating in or monitoring abusive interrogations. The APA claimed to be taking a firm stand on the issue, but critics, including Steven Reisner and me, were unconvinced. The Hoffman Report confirms critics’ worst fears, providing numerous detailed examples illustrating how APA officials reworded its own policies and resolutions to render them toothless.

When we met with the board, we challenged its members to embrace genuine contrition and take personal responsibility. But most importantly, we challenged them to transform the APA culture in order to place transparency, accountability, and inclusiveness as its core values.

Steven and I left encouraged that the board did understand the magnitude of the crisis facing not only the APA, but the entire psychology profession. We expected clear communication and resolute action. Alas, hours after the New York Times posted the leaked Hoffman Report the following week, the APA responded with a disappointing press release that downplayed the report’s key findings and instead placed the blame on a small number of rogue individuals. One of those individuals was later fired, and three others resigned with effusive praise from the board. A number of complicit staff remain in key positions, meanwhile.

Perhaps the APA Board and the larger council of representatives meeting in early August will wake up and enact real, resolute policy changes. If it does not, APA risks mass resignations and a potentially catastrophic loss in public confidence.

At stake is not solely the future of the APA and the reputation of the psychology profession. If the public does not have faith that psychologists’ prime commitment is to improving human welfare, public willingness to bare deep personal secrets to those claiming to help them could be impaired and support for psychological research reduced. If that happens, our whole society could suffer.