How the Mast Brothers fooled the world into paying $10 a bar for crappy hipster chocolate

Whether you’ve seen their beautifully wrapped bars for sale at Shake Shack or Rag & Bone, featured in the pages of the New York Times or Vogue, or decorating one of their New York, London, or soon, LA shops, Mast Brothers chocolate bars have become the world’s most prominent brand of artisanal chocolate.

Whether you’ve seen their beautifully wrapped bars for sale at Shake Shack or Rag & Bone, featured in the pages of the New York Times or Vogue, or decorating one of their New York, London, or soon, LA shops, Mast Brothers chocolate bars have become the world’s most prominent brand of artisanal chocolate.

But while customers can’t get enough of the company’s bearded, Brooklyn hipster founders, and their brilliantly marketed, $10 “bean to bar” chocolates, a term reserved for chocolate that has been produced entirely under the maker’s control, from the cocoa bean to the wrapped bar, chocolate experts have shunned them. Earlier this year, Slate published a story on Rick and Michael Mast, detailing complaints by the craft chocolate community about their undeserved media attention and unparalleled hubris. (“I can affirm that we make the best chocolate in the world,” Rick told Vanity Fair in February.)

Now, in “Mast Brothers: What Lies Beneath the Beards,” a new series of posts on DallasFood.org, Scott, the first-name-only blogger who in 2006 presented detailed allegations that the now-defunct Noka Chocolate was selling another company’s chocolate at significantly higher prices, has targeted the Mast Brothers’ story. He alleges that the company—whose business is staked on its authenticity and commitment to transparency—did not originally make its own chocolate from scratch, as it claims it always has. As artisanal food surges in popularity, whether it’s chocolate, liquor or jam, the Mast Brothers’ story highlights how a company can have great success selling a product of dubious quality as something “artisanal” or “handcrafted” with beautiful packaging and handsome, bearded founders.

“This has been an open secret in the chocolate industry,” Clay Gordon, a chocolate expert with 15 years of experience in chocolate, including as a consultant to chocolate makers on ingredient sourcing and equipment and as a former lecturer on chocolate and wine pairings through New York University and the James Beard Foundation, told Quartz. The clues were everywhere for anyone paying close attention, but the media missed them. Quartz has independently verified many of Scott’s claims.

Mast Brothers repeatedly declined to answer specific questions. In a statement provided to Quartz by the company’s public relations agency (and since posted on its website), the brothers said: “Any insinuation that Mast Brothers was not, is not or will not be a bean to bar chocolate maker is incorrect and misinformed. We have been making chocolate from bean to bar and will continue to do so. Through the years, we have continuously improved our methods, recipes and tastes. We love making chocolate, and we have the audacity to think that we are pretty good at it too.”

Mast Brothers obscure the fact that they originally used remelted, mass-produced chocolate

As they tell it, the Mast Brothers story is a tale of creativity and invention, an American dream with a hipster twist. Two Iowa-born, Williamsburg-living brothers taught themselves to make bean-to-bar chocolate. Incorporating their company in 2007, they wrapped their chocolate in expensive, beautiful paper and sold it for $10 per bar. Customers loved them, and what began in their apartment led them to a bigger space. By the summer of 2008, they were running a small Brooklyn factory; by November 2011, it had expanded another 3,000 square feet; and by January 2014, they had opened up a new factory in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. They opened in London in time for Valentine’s Day 2015 and the Los Angeles store is expected this spring. Now, as a tour guide at the Brooklyn retail location told Quartz, the Williamsburg spot alone pulled in $28,000 in chocolate sales in just one December weekend.

But there is evidence that at least some of their early production involved remelting chocolate bought from Valrhona, a commercial French chocolate manufacturer.

In the chocolate community, the suspicions of remelting began early. The Mast Brothers’ original bars had a taste and texture that was too much like the palate-friendly kind available at the drug store to be truly “bean to bar,” Scott explains in his first post. Bean-to-bar chocolate has a distinctive taste that, like wine, ties it to its origin, and craft chocolate makers use minimal processing to retain that taste.

“I was confident that they did not make the chocolate at that time,” Aubrey Lindley, co-owner of craft chocolate shop Cacao in Portland, Oregon told Scott and confirmed to Quartz. “It had an overly refined, smooth texture that is a trademark of industrial chocolate. No small equipment was achieving a texture like that. It also tasted like industrial chocolate: balanced, flavorless, dark roast, and vanilla.”

While multiple chocolate experts echoed these sentiments to both Scott and to Quartz, in part four of his series, Scott provides accounts from multiple sources who spoke to the Masts—over email, on the phone and in person—about their use of Valrhona chocolate.

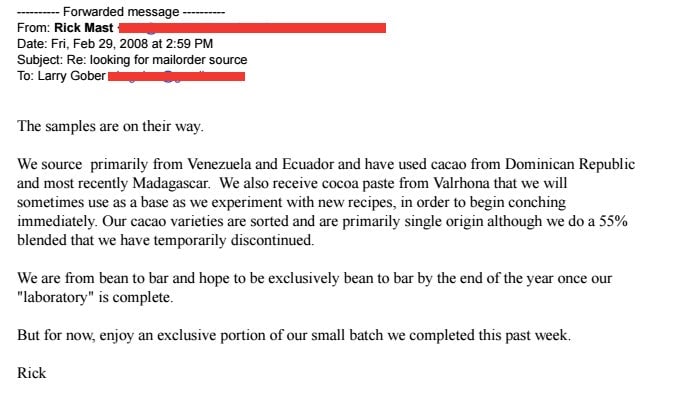

In February 2008, Oklahoma chef Larry Gober reached out to Rick Mast about buying Mast Brothers chocolate, as shown in emails on the DallasFood blog and provided to Quartz. He also asked where they were sourcing their chocolate from. Rick told him that they mostly sourced from Venezuela, Ecuador, Dominican Republic and Madagascar. “We also receive cocoa paste from Valrhona that we will sometimes use as a base as we experiment with new recipes,” they told him. “We are from bean to bar and hope to be exclusively bean to bar by the end of the year once our ‘laboratory’ is complete.”.

But they also told other chocolate makers that they had included Valrhona chocolate in products. On the phone with Alan McClure, founder of Patric Chocolate, a craft chocolate company formed in 2006, in the spring of 2008, Rick Mast admitted that they had used some remelted Valrhona chocolate but weren’t doing it any longer. (McClure confirmed this conversation with Quartz.)

That June, though, Art Pollard, co-founder of the bean-to-bar chocolate company, Amano Artisan Chocolate, was introduced to the brothers as they were selling their bars at the Brooklyn Flea, a weekend flea market in New York, including a dark milk, Trinidad single-origin bar. He had already heard about the brothers, and was curious to meet them. He saw they were selling six varieties of bars. “I wasn’t accusing,” he tells Quartz. “I was just amazed they were able to pull that off right from the beginning.” Coming up with just a single new bar is “a royal pain in the butt,” he says. He asked the then-beardless brothers about their sourcing since he had had trouble getting cocoa beans from Trinidad himself. “These three bars are ones that we made,” the Masts told him. “And these other three,” pointing to the single-origin and dark milk chocolate varieties, ”are Valrhona.” (Pollard told Quartz that other chocolate experts who were with him that day remember hearing those comments, but don’t want to speak to the press.)

These accounts contradict the statement from the Mast Brothers PR team which stated, “We made our chocolate from ‘bean to bar’ when we started.” Similarly, in a response to an inquiry from Grub Street, the Mast Brothers wrote, “Needless to say, we were then and are now a bean to bar chocolate maker.”

Eventually, however, experts believe that Michael and Rick Mast did start making at least some of their own chocolate, and as Scott explains, the quality of their bars dropped. ”The change was remarkable and obvious,” Lindley, of the Cacao shop in Portland, says of trying the bars in 2010. “Most of the chocolate was simply inedible, by my standards.”

The Mast Brothers are not as original and innovative as they have claimed

Part of the Mast Brothers’ story is that the brothers are self-taught chocolate-making MacGyvers, the first of their kind, inventing and rejiggering equipment to fit their chocolate needs.

“We’ve had to come up with how everything is done every step of the way because there was no such thing as small-batch chocolate makers,” Rick told an Australian publication.

Their 2013 cookbook, Mast Brothers Chocolate: A Family Cookbook, describes “roasting in a coffee drum roaster… three pounds of beans at a time,” “cracking cacao shells with a hand mill used for crushing barley in home brewing,” and “winnow[ing] the husks from the nibs using fans, or even hair dryers.”

“There’s no such thing as commercial equipment for [small-batch chocolate making]. You can’t say, I’m going to start a small chocolate company and then go online and get a couple of machines,” they told NPR in 2010.

The tour guide at the Williamsburg factory told Quartz that the brothers figured everything out themselves through “trial and error,” referencing only ancient Incan or Mayan (she couldn’t remember which) techniques.

But in reality, by the time Michael and Rick started making and selling chocolate in 2007, there were already a number of American small-batch chocolate makers on the market, as one of the proprietors of those businesses, Shawn Askinosie of Askinosie Chocolate, wrote for the Huffington Post earlier this year. Scharffen Berger was founded in 1997, Askinosie started in 2005, and Theo sold its first organic chocolate in 2006, just to name a few.

(In the cookbook the Mast brothers played a little safer, saying that when they started, “barely a handful of companies were actually making chocolate from scratch in North America.”)

In truth, despite their claim that they “had come up with how everything is done every step of the way,” the Masts picked up at least some of their knowledge on the thriving online community of chocolate makers that has existed for more than a decade. A public website, Chocolate Alchemy, is a hub of information, where chocolate makers could trade tips and advice for making small-batch chocolate. The website even included the tip about the blowdryer. Its earliest posts are dated October 3, 2003.

This site is also where the brothers bought some of their first equipment, as the founder, John Nanci, has confirmed to Quartz. In March 2009, on a tour of the first Williamsburg factory site, George Gensler—a co-founder of the Manhattan Chocolate Society and member of the Grand Jury for the International Chocolate Awards—saw and photographed the “Crankandstein Cocoa Mill,” developed in collaboration with Nanci specifically for the purpose of cracking cacao shells. Nanci has confirmed to Quartz that he sold the machine to Michael Mast on March 13, 2008. The note from Mast included in the order read, “We can’t thank you enough for all you have done. Your site is amazing.” Mast also separately ordered a 70kg bag of organic cocoa beans from the Dominican Republic with the note “Thanks for all of your incredible work and information. We could never have done this without you.”

Mast Brothers have executed a brilliant marketing strategy, but don’t sell quality chocolate

To Georg Bernardini, author of Chocolate—The Reference Standard, aka “The Chocolate Bible,” which includes reviews of over 500 chocolate companies’ bars, the marketing—not the chocolate—is Mast Brothers’ legacy. “It is not an ingenious story of passion for cocoa, instead a sophisticated marketing strategy, to earn as much money as possible as fast as possible,” he writes in the 2015 edition.

Even beyond the allegations of not being truly “bean-to-bar”, all the chocolate makers and experts Quartz spoke to expressed a gripe about the Mast Brothers’ past and current lines: The chocolate just isn’t very good. ”This year’s tasting was anything but a pleasure,” Bernardini writes in the 2015 edition of his chocolate guide. “The cocoa beans are virtually mistreated by the Mast Brothers.”

Mark Christian of the C-Spot, a chocolate review website, was slightly kinder in his overall assessment, telling Quartz that it swings from good to bad. “Starts out quite enticing, takes an interim dive, then improves for awhile, now currently quite abysmal,” he writes in an email. “Whether they ever again reach peak levels depends on their whim to shift attention back to hi-craft (outsourced or in-house) instead of concentrating overwhelmingly on the business of branding (quite a success).”

The company’s price of around $10 per bar is not unheard-of in the world of artisanal chocolate, but certainly on the higher end. “We charge $8 for most of our bars and our chocolate regularly receives awards in Europe for its taste and flavor,” Pollard of Amano Artisan Chocolate told Quartz. “Charging $10 for a bar made with beans that are not highly prized should be an exception rather than the rule.”

The paper the chocolate is wrapped in, on the other hand, Bernardini calls “almost magnificent.” As Scott shows on Storify, for many fans, “the packaging is the product.”

The Mast Brothers have packaged themselves brilliantly as well.

Ironically, some chocolate makers nonetheless see a silver lining in the Mast Brothers’ success. Chocolate experts are ”really unhappy that the brand has grown as a result of misleading people,” says Gordon. “But by the same token, they’ve been this important gateway chocolate.” Thanks to Mast Brothers, spending a lot of money on chocolate doesn’t seem like such a leap.

“If they did mislead consumers, it is deeply disappointing,” Sam Lehr and Derek Menaldino, co-founders of MUCHOMAS Chocolate, a relatively young craft chocolate company established in 2014, told Quartz over email. “Yet the fact remains that they are one of the craft chocolate world’s great ambassadors.”

The company celebrates transparency but turns out to be incredibly opaque

It is impossible to know whether or not the company is currently making chocolate entirely bean-to-bar because, as several experts pointed out to Quartz, there is no transparency.

In their cookbook, the Mast Brothers propound on the importance of transparency as early as page 5. “Be honest and transparent. We demand integrity in everything we do and eagerly open ourselves up to the world with pride. That’s why we opened a craft chocolate factory in the middle of New York City!”

But throughout the writing of this story, the company has refused to answer any specific questions, from whether Mast Brothers has investors to what kind of equipment the company uses. At its Williamsburg factory, the tour instructions were explicit: no photographs and no notes. The Brooklyn Navy Yard factory, where the tour guide said about two-thirds of the company’s production is done, is closed to the public.

They have also stopped listing the source of the beans, omitting one of the most critical elements of a bean-to-bar chocolate label, despite proclamations in their book about “connect[ing] customers to the source.” The 2016 line of flavored bars, which include sheep’s milk, mint, and olive oil, no longer lists bean origin, though a tour guide at the Williamsburg location said they are still single-origin with just a couple of exceptions. The guide cited two reasons for not listing the origins: Because it encourages more conversation between retailers and customers—even though a lot of chocolate is sold off premises and wholesale—and because it looks better aesthetically to have less information on the label.

Other chocolate makers offer a different explanation: “It means that it could be virtually anything,” Pollard told Quartz.

Transparency is important to all elements of the food movement, but it is particularly relevant in the realm of chocolate, Carla Martin, lecturer on African and African American Studies at Harvard University, and founder and executive director of the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute, told Quartz. She cites examples like Cadbury’s ignoring the use of slave labor in its supply chain in the early 1900s, and early industrial chocolate makers who were found to be bulking up chocolate with corn sugar. “It’s something that people involved in the craft chocolate movement are very concerned with,” she says. “There are ideals about this kind of openness in one’s business practices and it comes from very real concerns about fraudulent practices in the food industry.” Similar concerns continue to the present day: Most of the world’s chocolate comes from West Africa, where practices like child labor and rainforest clearing are rampant.

It’s easy to attribute all of the negative comments to resentment from other chocolate makers—Mast Brothers gets incredible press from a range of publications all over the world. “There is a certain kind of jealousy,” Bernardini told Quartz over email, “but more of an anger.” ”But [chocolate makers] should also be angry with the media as it is the fault and responsibility of the media that Mast Brothers became so famous (with a mediocre and sometimes also bad quality). Only because they wore clothes like Amish people with long beards.”