Why is Central Africa missing from so many maps?

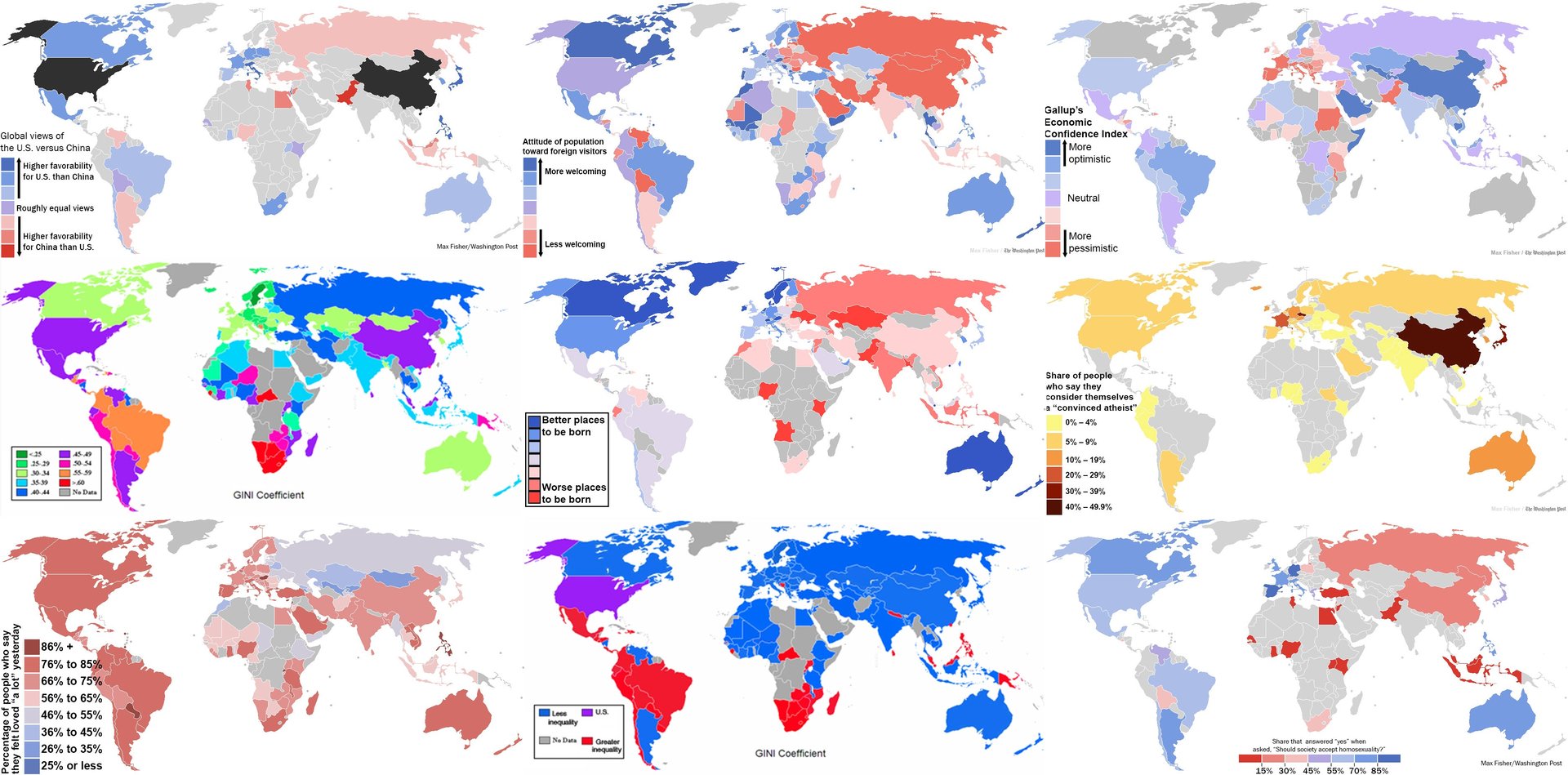

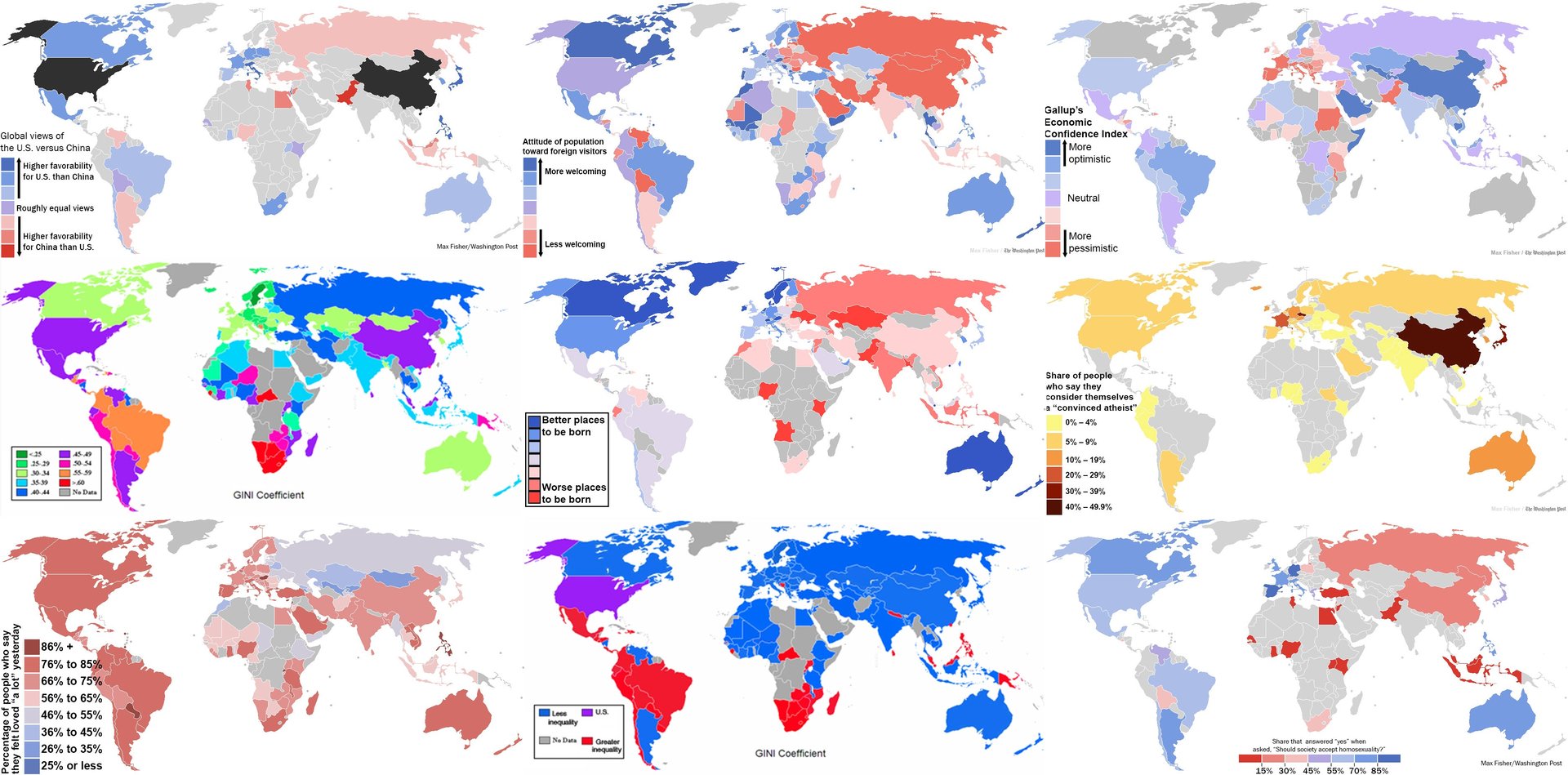

You’ve probably had the following experience: You are reading along when a map, shaded in a procession of pastels, interrupts the story. Your eyes travel first to your home country, then to the country where you spent a summer abroad, and then, finally, sweep around the map looking for the brightest or dimmest shades that mark a place is the most or least of something. Along the way you cross a vast colorless expanse where Central Africa should be. “No data,” the legend explains.

You’ve probably had the following experience: You are reading along when a map, shaded in a procession of pastels, interrupts the story. Your eyes travel first to your home country, then to the country where you spent a summer abroad, and then, finally, sweep around the map looking for the brightest or dimmest shades that mark a place is the most or least of something. Along the way you cross a vast colorless expanse where Central Africa should be. “No data,” the legend explains.

This gap appears across a huge range of subjects that have inadequate source data for developing countries. Often all of Sub-Saharan Africa is missing, but it is the Central African countries that seem to disappear most frequently. Central Africa is defined by the UN to include nine countries. It extends from the tiny island nation of São Tomé & Príncipe to the expansive, resource-wealthy Democratic Republic of the Congo. Estimates—and they are only estimates—put Central Africa’s total population at just under 150 million people.

No data

The gap is a pervasive problem. In a 2013 Washington Post article titled “40 maps that explain the world,” at least half of the maps that included Africa were missing one or more Central African countries. Of those, many were missing data for the entire region. Somehow it is common to ”explain the world” while saying little about a populated area nearly the size of Australia. In addition to perpetuating the historical bias of minimizing Africa on maps, this lack of information is indicative of many of the challenges these countries face.

El Iza Mohamedou is deputy secretariat manager for PARIS21, one of the most important initiatives to improve statistical capacity in developing countries. Speaking on her own behalf, she told Quartz that a lack of vital statistics makes it impossible to adequately monitor issues like poverty and maternal health—or to evaluate the success of policies aimed at improving them. “Countries with the least satisfactory data on deaths and births, and whose maternal mortality rates have to rely on estimation, are exactly the ones where the maternal mortality problem is the severest,” she said.

Given the lack of solid data on poverty and health, it’s no surprise that data is also missing for more nuanced issues. For example, a report in 2015 found that, globally, data for 80% of the essential indicators for progress on gender issues are missing. In Sub-Saharan Africa 82% were missing. This makes it impossible to judge the scale of the problems and means there is no way of knowing if the strategies to reduce gender inequalities are effective. For example, would a particular country benefit more from an investment in maternal healthcare or early childhood education?

The World Bank rates developing countries’ statistical capacity with an index that tracks whether they measure important things and, if so, how often. Central African countries consistently score among the lowest on this measure. None of them have complete records of births and deaths—one of the most essential datasets to the smooth operation of government.

Other than their location and a lack of data, there is not too much else in common with all Central African countries. A large, fragile state such as Central African Republic faces a different set of challenges than a smaller and more stable state such as Gabon.

As with Africa as a whole, caution must be used when making broad generalizations about problems and solutions. However, what these countries do have in common is very relevant to their statistical needs. The majority of their citizens are poor, they all face some amount of food insecurity, and they are all recipients of significant foreign aid.

In light of the substantial challenges facing most of the Central African countries, hand-wringing about the need for data can be easily misinterpreted as naive or arrogant. However, the reality is that the solutions are often inseparable from the statistics. Schools aren’t constructed without knowing how many children need to be educated. Famines sweep across countries that don’t know what is growing or where. Businesses take their investment to countries that can tell them what resources will be available. Perhaps most importantly, development programs should—and increasingly do—require measurable results. Without data it is impossible to know where aid is actually working.

Bad data

Missing statistics are not the only problem. Measures must also be accurate enough to form the basis for effective policy. Many of the published statistics for African countries are known to be based on flawed or incomplete sources. According to Morton Jerven, an economist who has published two books about problems with African statistics, “Presidents are elected, rejected and reelected on the promise of creating more jobs, yet most of these presidents would not have the faintest idea of how big unemployment is, whether [it] is going up or down, or even where people work or where they want to work.”

Economics are probably where bad data has been the most visible. In his 2013 book, Poor Numbers, Jerven lists many deficiencies in African states’ national accounting. The very next year revisions to GDP calculations in some of those countries found that they they were off by as much as half. Most Central African countries have not yet aligned their national accounts to global standards and are likely to be subject to similarly skewed statistics.

Problems are by no means limited to the data published within the countries. The United Nations’ oft trumpeted Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are a particularly dramatic illustration. These goals are evaluated using local statistical indicators, such as childhood immunization rates and the percentage of residents with mobile phones. They drive development efforts around the world, but nowhere more than in Sub-Saharan Africa. When local data is not available, the UN fills in the gaps. In 2015, 65% of the MDG indicators for Central African countries were either estimated, derived from statistical models, or were last measured prior to 2010.

In 2016 the United Nations will move from the Millennium Development Goals to the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These new goals use many of the same indicators, but also expand into a broader set of issues—some of which are even more difficult to measure. An interagency group organized by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network has estimated (pdf) that it would cost a minimum of $1.1 billion per year to raise the 77 least developed economies up to the point where they could measure the SDGs effectively.

With so much dependent on statistics and so many challenges to measuring them accurately, the incentives to manipulate the numbers are tremendous. Want to receive additional aid for education? Simply tweak the numbers to show your programs are working. It’s almost impossible to say how widespread such issues are, but across Africa surveys consistently rank corruption as one of the most significant barriers to economic progress.

Solutions

Local and international decision-makers acknowledge there are problems. The 2015 Millennium Development Goals report (pdf) begins with a four-page acknowledgement of the need for better data from developing countries. Another UN report titled A World that Counts (pdf) summarized the many challenges and began a widely sounded call for a “data revolution.” Their stated goal aims very high: “Never again should it be possible to say ‘we didn’t know.’ No one should be invisible.” Similar aspirations have been in circulation since at least the early nineties.

The World Bank, the African Development Bank and others have put forward a head-spinning number of proposals, plans, and symposiums aimed at developing statistical capacity in Africa. PARIS21, which is housed in the OECD, tracks global aid money committed to statistical capacity building projects. Since 2006 the total amount varied between $250 million and $500 million per year. This might sound like a lot of money, but it’s less than half a percent of the all aid provided directly by countries. Total statistical aid recorded to Central African countries over those nine years adds up to less than a dollar per person—and the vast majority of that was spent in the Central African Republic.

Despite such limited investment there have been some improvements. From 2006 to 2015 World Bank capacity indicators for Central African countries improved by an average of 16%. According to the PARIS21 annual reports most African nations either now have or are currently developing a national strategy for statistics. Grant Cameron, who manages development programs for the World Bank, told Quartz that demand for statistical training and support “is on the upswing.” Some commenters have been so exuberant about recent progress as to declare the data revolution well underway (pdf), though so far these seem to be the exception, rather than the rule.

Meanwhile, non-governmental organizations are also getting involved in collecting and publishing data. The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team use satellite imagery to map crisis areas that don’t have up-to-date geographic information. They’ve done extensive work in the Central African Republic. Others, such as Code for Africa, are focused on freeing up the bits and pieces of data that already exist. The continent’s first open data conference was held in Tanzania last year. Even Africa’s nascent startup scene is getting involved in areas such as agricultural data.

The sheer number of solutions being pursued is some cause for optimism, but ultimately it will be individual African countries that must accomplish the most challenging part of the work. Cameron, echoing a Center for Global Development report (pdf), pointed to the need for governments to invest in strong, independent national statistical offices. Those agencies will need consistent funding as well as checks against corruption and insulation from political whims. Only then can international aid and technical support be effective in helping them to reach new milestones.

Producing better data is just one step on the path to solving more urgent and tangible problems in Central Africa. However, it is an essential step. Policy makers need it. Aid organizations need it. Businesses need it. And, in a world where political, economic, and medical decisions are made on an international stage, the world needs it too. That vast gray gap on the map of the Earth isn’t just journalistic laziness. It is one of the few concrete symptoms those in the developed world ever see of the challenges that Central Africans face. So long as the gap is there, so are the problems.