How Amazon is secretly building its superfast delivery empire

Delivery in a day is just too slow. At least, that seems to be the philosophy at Amazon, which in the last year has quietly built out a network of at least 58 Amazon Prime Now hubs in the US to fulfill one- and two-hour deliveries.

Delivery in a day is just too slow. At least, that seems to be the philosophy at Amazon, which in the last year has quietly built out a network of at least 58 Amazon Prime Now hubs in the US to fulfill one- and two-hour deliveries.

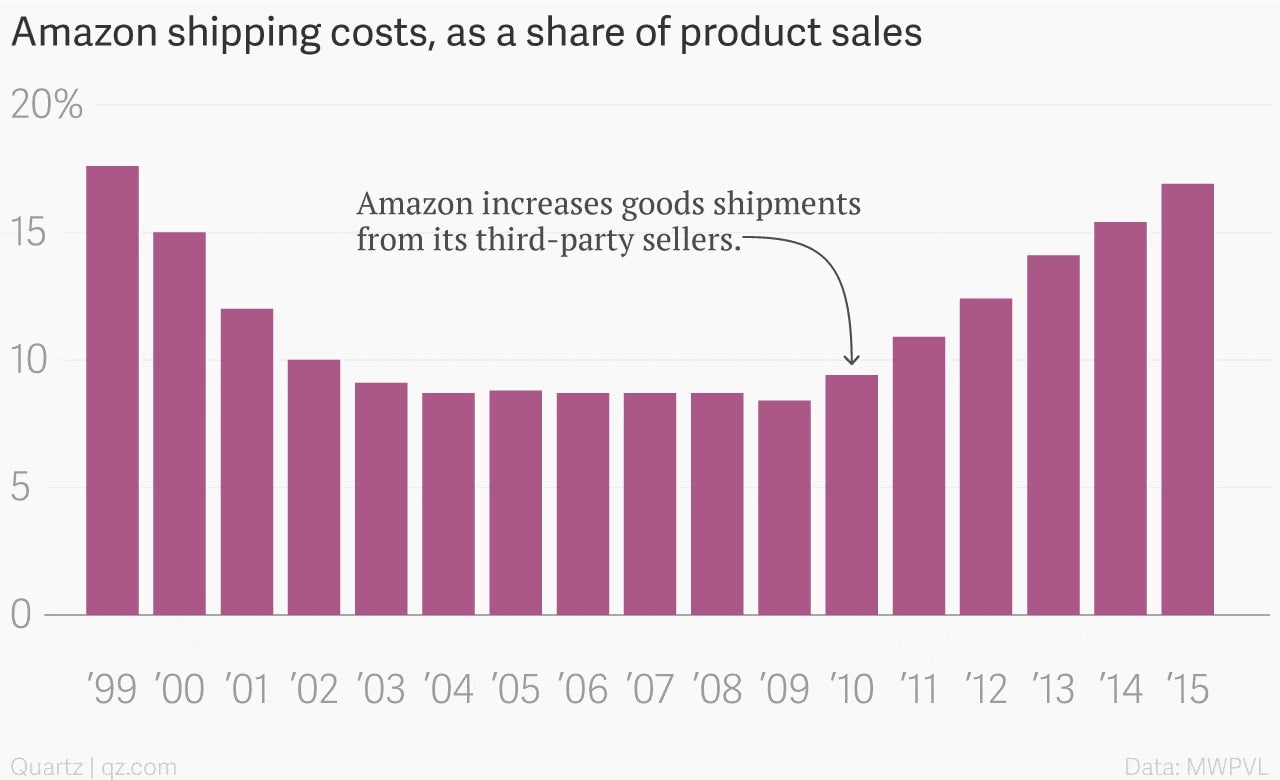

The buildout of the Prime Now hubs goes toward the goal of getting goods to the market faster, but it’s also one cog in a larger strategy to create a lean, cost-efficient logistics network that rivals anything its competitors can offer. That’s an important step for Amazon, which loses billions of dollars getting goods to consumers.

Those hyper-fast deliveries are available to Prime Now customers living in the high-density urban areas where the hubs have been built, said Marc Wulfraat, president of logistics consultancy MWPVL, in a presentation hosted by SunTrust on Thursday (March 11). The new warehouses—typically 50,000 to 60,000 square feet—are fed by Amazon’s 86 gargantuan fulfillment centers, but only with about 10,000 bestselling items as rated by the company’s internal data. Wulfraat said he could confirm 58 Prime Now hubs, but there could be more.

“This has probably been the most secretive piece of data that the company has not been talking about,” he said during the presentation, adding that the Prime Now hubs amount to Amazon’s equivalent of having retail stores.

“My take on it is that the less that people know about this the better,” Wulfraat told Quartz. “They are not even publishing the addressed locations of these buildings; they are unmarked.”

An Amazon spokeswoman would not say how many hubs the company has built, only that Prime Now is available to customers in more than 25 metropolitan areas.

To slice away at shipping costs, the company is eliminating the middlemen in China who deliver goods from warehouses to seaports, opting to bring that job in-house. It also bought thousands of tractor trailers (not the trucks) to more efficiently load and ship goods. And most recently, Amazon announced it’s leasing 20 Boeing 767s to deliver its own goods to and from its fulfillment centers, a move that diminishes the company’s reliance on third-party shippers such as FedEx and United Parcel Service. The company’s flight hub will be in Wilmington, Ohio.

The new Prime Now hubs are one of three types of warehouses the company is running to further reduce third-party delivery costs. In addition to its fulfillment centers, it began in 2013 to build so-called sortation centers. Those warehouses are meant for nearby small-parcel shipping, which allow the company to shift deliveries from FedEx and UPS to the less-expensive US Postal Service, Wulfraat said.

“Nobody beats the post office when it comes to taking the cost out of shipping,” he added.

For example, if a customer in Boston bought a one-pound item through Amazon online, it was then shipped from the Breinigsville, Pennsylvania, fulfillment center by FedEx or UPS for about $4.50. Now, Boston shipments can be sent to a sortation center in Stoughton, Massachusetts, where the US Postal Service delivers the package for about 80% less.

It’s going to take several years before Amazon figures out the best way to rein in the costs of shipping, Wulfraat said, especially as the company adds more customers, promises faster delivery times, and hires more people to make those shipments happen. By taking control over pieces of its delivery network and integrating things such as company-leased planes, a good portion of that total cost will be shed.