The Economist’s website is now censored in China—and all it took was one satirical cover

A bold denouncement of Xi Jinping will typically get censored very quickly in China.

A bold denouncement of Xi Jinping will typically get censored very quickly in China.

So it’s not surprising that the Economist, the 171-year-old business news publication, is the latest foreign publication to face an online ban in the Middle Kingdom.

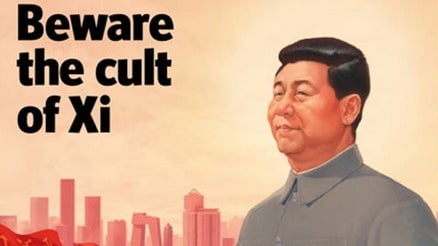

On April 2, the magazine published an issue with a cover that depicts Xi Jinping in the same artistic style as Mao-era propaganda. The premier wears revolutionary-era Communist attire, and stares omnipotently in front of pedestrians holding flags that bear his name.

Our cover this week: “Beware the cult of Xi”. Xi Jinping, the Chinese leader, has one all-consuming project: the pursuit of power. Share a photo of you reading your copy using #myeconomist and we’ll repost our favourite image next week #TheEconomist #China

A photo posted by The Economist (@theeconomist) on Mar 31, 2016 at 7:01pm PDT

The corresponding article condemns Xi Jinping’s anti-graft campaign, crackdown on internet freedom, and failure to welcome market forces into China’s economy. In 1,000 words, it argues that his self-promotion and concentration of power has only weakened his ability to govern.

By cracking down and puffing himself up, Mr Xi is neither buying himself security nor helping to keep China stable. He is using the party’s own thuggish investigators to take on graft. But they have a greater interest in settling political scores than in ensuring laws are applied fairly. That gets in the way of good administration, if only because officials are scared of spending money in case it attracts a probe.

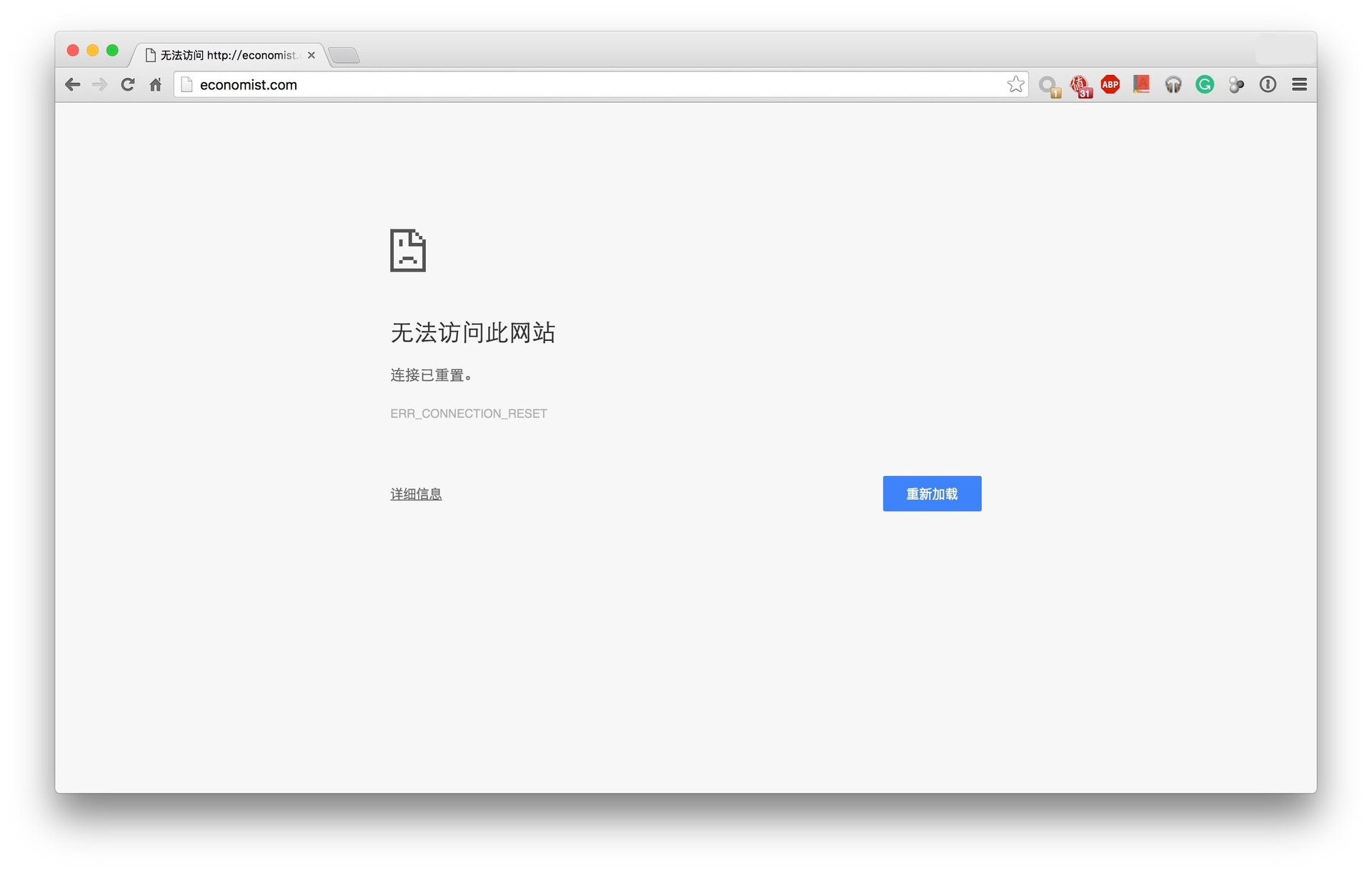

China’s internet authorities acted swiftly.

According to Greatfire.org, an organization that tracks internet access in China, the URL www.economist.com has been blocked intermittently since April 1. Quartz meanwhile reached out to three internet users in China and all of them were unable to reach the publication’s website. At present, entering the Economist’s URL into the address bar took them to an error page.

Vijay Vaitheeswaran, an editor at the Economist’s China bureau, confirmed to Quartz that the company believes that the Economist’s website and English-language app are currently blocked in China. He added the company also believes that the WeChat accounts for the Economist Group and the Economist’s recently-launched Global Business Review have been suspended. Vaitheeswaran declined to comment further.

This marks the first complete block of the entire Economist website in mainland China. In the past, the site faced partial online blocks of specific articles discussing China. Its print circulation was never completely stopped, but articles from its China section would occasionally be ripped out before editions hit local newsstands there. The magazine had 8,000 subscribers in mainland China and another 11,000 in Hong Kong as of a year ago.

The Economist, like the New York Times, the Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, and Reuters, has made attempts to expand its readership by targeting Chinese readers. In April 2015, the company made its first-ever foray into multi-lingual publishing when it launched the Global Business Review, which publishes selected articles from the magazine in both Chinese and English. When the app went live, the Economist promised that it would not self-censor the content.

“So selection of stories has not been chosen with the sensitivities or indeed interests of a particular country in mind,” Tom Standage, deputy editor of the Economist, told Ad Age at the time of its release. “Of course, some business stories have political angles to them, and that may cause problems in some markets. If it does, then so be it; but we are not going to censor ourselves or try to second-guess how the authorities in particular countries might react.”

At present, the Economist’s Global Business Review app has not been blocked—but it also did not carry the controversial Xi story in Chinese nor in English. A majority of the articles shown in the app are business and finance related. China-centric pieces in updates dating back to January include pieces about China’s trade with India, China’s industrial overcapacity, China’s semiconductor industry, China’s acquisitions of foreign companies, and China’s stock market. But there are no articles that directly address politics in China—or any other country, for that matter. Quartz did not receive a response to questions about the app’s content.

Most of the Economist’s peers had their Chinese-language websites blocked long ago, for carrying stories that upset China’s government. Now the Economist has joined their ranks.