Mexico City is crowdsourcing its new constitution using Change.org in a democracy experiment

Mexico City just launched a massive experiment in digital democracy. It is asking its nearly 9 million residents to help draft a new constitution through social media.

Mexico City just launched a massive experiment in digital democracy. It is asking its nearly 9 million residents to help draft a new constitution through social media.

The crowdsourcing exercise is unprecedented in Mexico—and pretty much everywhere else. Chilangos, as locals are known, can petition for issues to be included in the constitution through Change.org (link in Spanish), and make their case in person if they gather more than 10,000 signatures. They can also annotate proposals by the constitution’s drafters via PubPub, an editing platform (Spanish) similar to Google Docs.

The idea, in the words of the mayor, Miguel Angel Mancera, is to “bestow the constitution project (Spanish) with a democratic, progressive, inclusive, civic and plural character.”

There’s a big catch, however. The constitutional assembly—the body that has the final word on the new city’s basic law—is under no obligation to consider any of the citizen input. And then there are the practical difficulties of collecting and summarizing the myriad of views dispersed throughout one of the world’s largest cities.

That makes Mexico City’s public-consultation experiment a big test for the people’s digital power, one being watched around the world.

A city is born

Fittingly, the idea of crowdsourcing a constitution came about in response to an attempt to limit people power.

For decades, city officials had fought to get out from under the thumb of the federal government, which had the final word on decisions such as who should be the city’s chief of police. This year, finally, they won a legal change that turns the Distrito Federal (federal district), similar to the US’s District of Columbia, into Ciudad de México (Mexico City), a more autonomous entity, more akin to a state. (Confusingly, it’s just part of the larger urban area also colloquially known as Mexico City, which spills into neighboring states.)

However, trying to retain some control, the Mexican congress decided that only 60% of the delegates to the city’s constitutional assembly would be elected by popular vote. The rest will be assigned by the president, congress, and Mancera, the mayor. Mancera is also the only one who can submit a draft constitution to the assembly.

Mancera’s response was to create a committee of some 30 citizens (Spanish), including politicians, human-rights advocates, journalists, and even a Paralympic gold medalist, to write his draft. He also called for the development of mechanisms to gather citizens’ “aspirations, values, and longing for freedom and justice” so they can be incorporated into the final document.

The mechanisms, embedded in an online platform (Spanish) that offers various ways to weigh in, were launched at the end of March and will collect inputs until September 1. The drafting group has until the middle of that month to file its text with the assembly, which has to approve the new constitution by the end of January.

An experiment with few precedents

Mexico City didn’t have a lot of examples to draw on, since not a lot of places have experience with crowdsourcing laws. In the US, a few local lawmakers have used Wiki pages and GitHub to draft bills, says Marilyn Bautista, a lecturer at Stanford Law School who has researched the practice. Iceland—with a population some 27 times smaller than Mexico City’s—famously had its citizens contribute to its constitution with input from social media. The effort failed after the new constitution got stuck in parliament.

In Mexico City, where many citizens already feel left out, the first big hurdle is to convince them it’s worth participating. According to a 2013 survey (Spanish, pdf) by Mexico’s national electoral authority:

- Most Mexicans, 66%, consider there is little or no respect for the law.

- Half of them see democracy as a system in which everyone participates but few benefit.

- Nearly a third have no trust in the federal government at all, and more than 40% distrust political parties and lawmakers.

- More than 70% don’t trust their fellow Mexicans.

To engage with its jaded residents, the city built the site with eye-catching drone video of the city.

And it’s been posting videos on YouTube of members of the drafting committee, encouraging citizens to participate. One of the drafters, Carlos Cruz—a former gang member who has created several programs to keep youth from getting involved in organized crime—talks about raising the minimum wage and reducing inequality (Spanish).

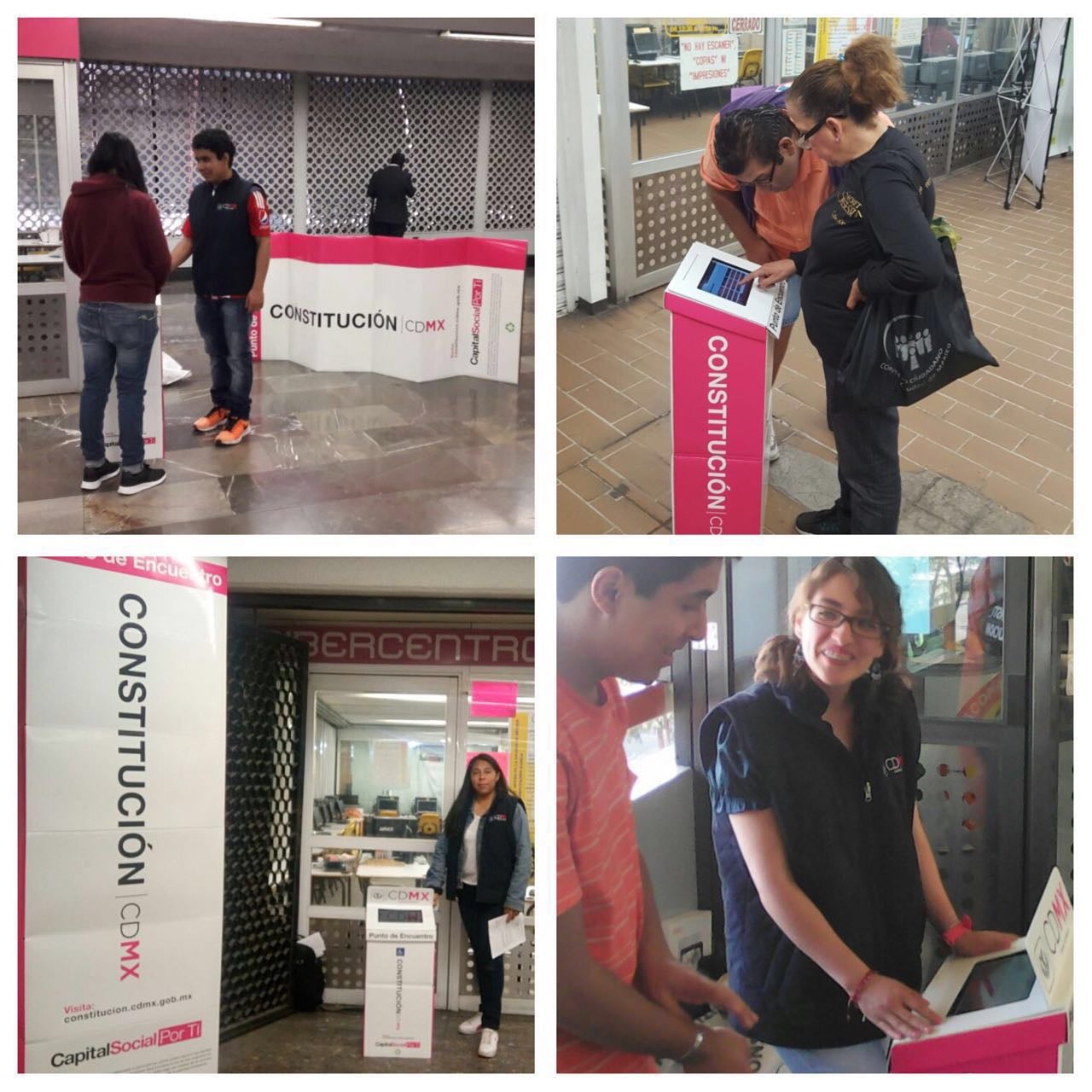

There are various levels of participation on offer, from ranking the city’s biggest problems in an online survey to making detailed comments on draft proposals. For people without internet access, 300 computer kiosks have been set up throughout the city with staff to guide them through the process.

“For this to be awesome, there have to be hundreds of thousands of answers,” said Diego Cuesy, a city policy analyst who helped build the platform.

Making sense of it all

Convincing chilangos to share their views is just the first step, though. Then comes the task of making sense of the cacophony that will likely emerge. Some of the input can be very easily organized—the results of the survey, for example, are being graphed in real time. But there could be thousands of documents and comments on the Change.org petitions and the editing platform.

Ideas are grouped into 18 topics, such as direct democracy, transparency and economic rights. They are prioritized based on the amount of support they’ve garnered and how relevant they are, said Bernardo Rivera, an adviser for the city. Drafters get a weekly delivery of summarized citizen petitions.

Audience by signature

The drafting group has pledged to respond to petitions on Change.org with more than 5,000 signatures, and to have a few of its members meet with petitioners who gather more than 10,000. More than 50,000 signatures earns an audience with the full committee.

The most elaborate part of the system is PubPub, an open publishing platform similar to Google Docs, which is based on a project originally developed by MIT’s Media Lab. The drafters are supposed to post essays on how to address constitutional issues, and potentially, the constitution draft itself, once there is one. Only they—or whoever they authorize—will be able to reword the original document.

User comments and edits are recorded on a side panel, with links to the portion of text they refer to. Another screen records every change, so everyone can track which suggestions have made it into the text. Members of the public can also vote comments up or down, or post their own essays.

But will it work?

In nearly three weeks, Change.org has collected more than 200 petitions, which have been signed by more than 10,000 people. So far the most popular, with some 3,500 supporters, calls for politicians to be considered service providers, not staffers, and to be paid only for the time they work and “not for weeks when all they are seen doing is sleeping or playing with their iPads.” The next most popular is about animal rights.

Meanwhile, on PubPub, only one member of the drafting group has published a document—a dense academic essay on the legal framework the city should use to protect human rights—which has picked up two annotations. A group of university students has added around 20 texts, though most of them remain unedited.

To be fair, it’s early days yet. Things may pick up as more events are held to get citizens engaged. But even if many of them participate, says Antonio Martínez, a digital rights lawyer, there’s nothing spelling out how the inflow of ideas will influence the drafting group’s decisions. “It’s a bit of a show,” he says.

Others argue that there’s still value in the platform even if all the citizen comments end up in some lawmaker’s drawer. Luis Fernández, president of Participating for Mexico, an NGO, says it will help generate discussion. “The more information there is about the topics that have to be incorporated, the more information sources constitutional delegates will have to better do their job,” he said.

Cuesy, from the city, admits that it’s hard to track whether and how citizens’ digital input can modify officials’ views and behavior. It’s a question that the city is trying to answer through the experiment. “We’re going through a learning curve,” he said.

Still, the platform represents, at the very least, a commitment by the government to listen, Cuesy added. There will also be an electronic record for everyone to see, and potentially to hold the constitutional assembly accountable if, for example, it skips a topic that hundreds of thousands of citizens said was key. (The top challenges for the nearly 15,000 people who have answered the survey so far are corruption and jobs.)

That’s an improvement over the demonstrations that frequently bring the city to a halt, Cuesy argued. ”I love protests,” he said. “But if I go out to the street, there is no legal mechanism that requires the drafting group to consider what I have to say.”