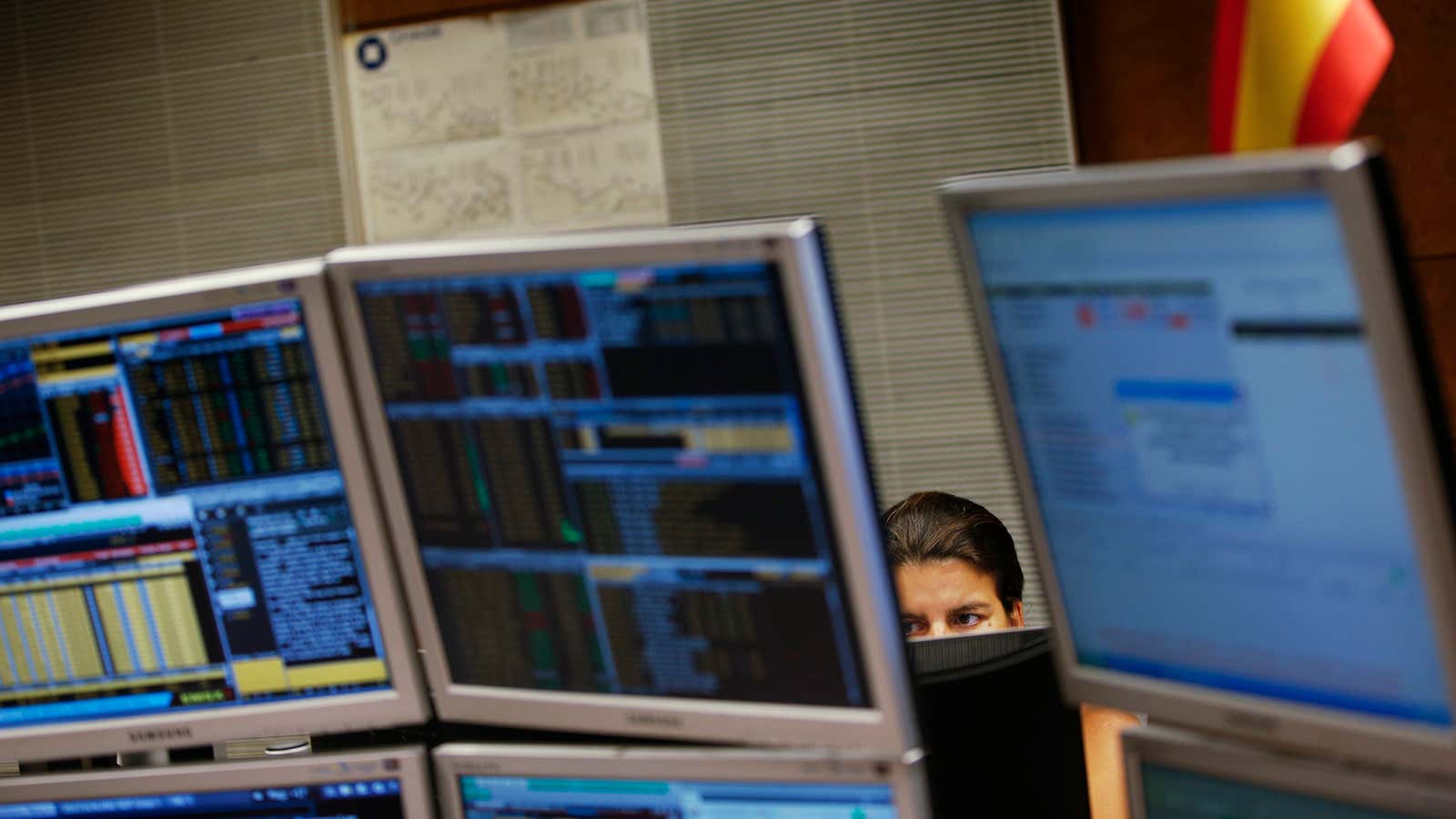

The real danger of the singularity isn’t that computers will conspire to overtake their masters, but that we’ll let them do it—and then be lost when they fail. This is already apparent in the number of major market crashes that have occurred on the watch of complex algorithms, according to some.

Our eagerness to rely on algorithms to get ahead, MIT Media Lab’s Kevin Slavin told Wired Money attendees on Monday, is revealing a unique set of weaknesses in the stock market. He cited a recent incident in which the Associated Press Twitter feed was hacked, resulting in a tweet that claimed the White House was under attack. “Only about 1,000 people actually believed this,” Slavin said, but it resulted in a huge market drop. “That’s what happens when you remove human evaluation and judgement from the system—it renders the system increasingly fragile, even in something as straightforward as the news.”

In an explanation of the Twitter-related market crash, Irene Aldrige, a quantitative portfolio manager at ABLE Alpha Trading, told Time that high-frequency trading algorithms, which allow computers to scan news sources for information that informs their millions of trades per second, had been fooled by the tweet. “If a trusted news source with a lot of followers like the Associated Press sends out those words,” (in this case, “White House,” “explosion,” and “Barack Obama”) she noted, “that may have triggered something.” That said, Aldrige added that “no long-term investors lost any money,” and that the market recovered quickly, so the incident shouldn’t keep us from using high-frequency trading.

Slavin would likely disagree: In his talk he noted that while algorithms often compute information much faster than humans, they lack the insight necessary to draw apt conclusions. The algorithm “figures it out not because it’s smart,” he said, “but because it seems smart without underlying sensibilities.”

“It’s the dark version of the singularity,” he continued. “Anything I’ve learned about giving computers autonomy is that they crash, so I’m not so much worried about them taking over as I am bout the present, in which they fail dramatically.” Slavin advocates for better human monitoring for the computer systems we’ve created, so that the market becomes “something built on human time, working together with machines.”