When Western officials have historically visited Africa, the major themes have been things like combatting poverty and fighting horrible diseases. So it was a bit of a departure for Obama to focus on investment and trade instead.

On his trip to the continent, Obama announced a $7 billion plan to build more power plants, invest in institutions, and work more closely with African heads of state. He also unveiled a new program, Trade Africa, to boost imports and exports both with and within the continent, starting with the East African region known as the EAC.

“The EAC is an economic success story, and represents a market with significant opportunity for U.S. exports and investment,” the White House said in a fact sheet.

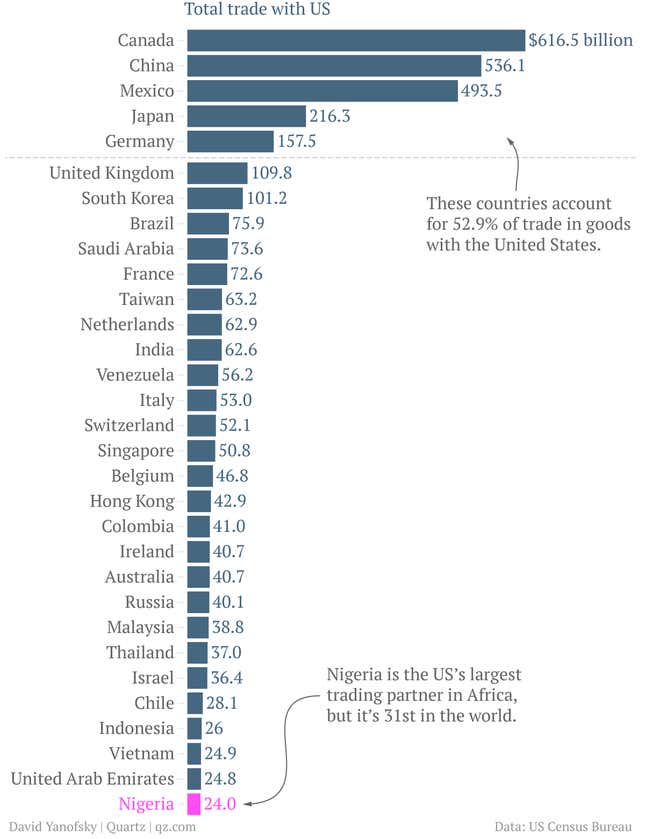

Overall, US trade with Africa has been tiny relative to the continent’s size:

Quartz

Nigeria is the US’s largest trading partner in Africa, but it only ranks 31st among all countries, as David Yanofsky reported.

The biggest obstacles are the myriad infrastructure and governance issues—everything from bad roads to corrupt leaders to clunky customs processes—that prevent goods from moving between African borders as smoothly as they could.

But with the new initiatives, the US seems to be looking to fix that, and here’s why:

1) Africa’s middle class is ballooning:

Sub-Saharan Africa is home to six of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies, and its middle class is set to triple to more than one billion people in the next half-century. About 42% of Africans will be earning between $4 and $20 a day (as opposed to $1 or $2, the general definition of “living in poverty”) by 2060, according to a report from the African Development Bank.

Its population is also incredibly young—more than half of Africans are under 20—so in a few decades it will have a massive working-age population.

Of course, this GDP growth doesn’t always get spread evenly among the population, and some countries have handled their booms better than others. Still, where there’s purchasing power, there’s business interest.

2) Many multinationals are looking for new, untapped markets:

There are only so many Americans who Harley Davidson can convince to buy a giant motorcycle. But Africa’s growth will eventually create whole new population of people who will, for the first time, have spending money.

“If you take a company like Unilever or Walmart, companies have an eye on this large retail opportunity,” Haroon Bhorat, a professor of economics at the University of Cape Town, told me. “Walmart now has fairly good global footprints, but nothing in Africa [until recently]. They realize there is a huge consumer market.”

As mining in Africa grows, Caterpillar is selling enormous trucks for hauling ore to Mozambique. Harley had a biker convention at a South African resort. Nestle recently said it wants to triple its African business by 2020.

China and other Asian countries have also doubled their African trade since 1990, so at this point the U.S. and Europe risk falling even further behind in emerging markets unless they jump in.

3) “Aid for trade”:

Obama’s visit signals a shift away from aid transfers—the more traditional way the Western world has engaged with Africa—and toward building trade relationships. But his recommendation to develop infrastructure also resembles the “aid for trade” philosophy of international development, or the idea that donations should aim to help countries create the kinds of systems that make buying and selling easier.

What’s more, much of Africa’s growth has been fueled by the extraction of minerals, which most economists agree is not the best path to creating lasting, sustainable growth like the kind Asia has seen. Instead, countries need manufacturing and services industries in order to truly cement their “rising” status.

“Africa’s growth tends to be concentrated on a limited range of commodities and the extractive industries,” a recent report by the African Development Bank states. “These sectors are not generating the employment opportunities that would allow the majority of the population to share in the benefits.”

Of course, many US companies remain averse to investing in risky places, and only a few African nations have fully made the transition from utter poverty to “success stories.” But if the initiative works, increased trade could provide the kind of broad economic base the continent needs in order to make even greater gains in reducing poverty.

Olga Khazan is The Atlantic’s global editor.

This originally appeared at The Atlantic. More from our sister site:

Do the U.S. and EU need couples therapy?

What’s the matter with TV news?

For Chinese students abroad, personal freedoms—not political—are what matter