Updated July 4, 11:30 a.m. ET

Egypt’s military, with the apparent backing of other political groups, overthrew president Mohamed Morsi on July 3 and replaced him with the little-known chief justice of Egypt’s Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC), Adly Mansour.

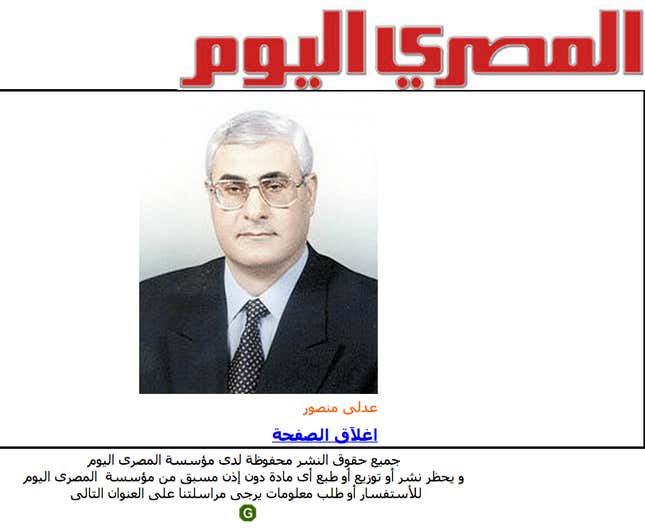

Mansour is a relative political nobody—such a nobody, in fact, that none of the world’s main news photo agencies had a picture of him as of July 3. The one below, of unknown origin, which appears on Al Masry Al Youm and several other Egyptian news sites as well as his Wikipedia page, is one of only two to be found online; several websites are erroneously using another one.

What we do know is that he is a career bureaucrat. Born December 23, 1945, he has three children (link in Arabic): Ahmed, Jasmin, and Basant. He’s a lawyer by trade, graduating from the University of Cairo in 1970 (Arabic). Mansour then joined the government as an assistant delegate in the State Council, part of Egypt’s judiciary, where he would spend much of his career.

The State Council “gives legal advice to the government, drafts legislation, and exercises jurisdiction over administrative cases,” explains Nathan Brown of the Carnegie Endowment, and “includes a set of administrative courts that adjudicate disputes in which a state body is a party.” Mansour worked his way up this system, serving at various advisory and administrative posts within the State Council. In addition to other duties, he spent 1983-1990 as a legal advisor in Saudi Arabia for the Egyptian ministry of commerce. He left the State Council in 1992 when he was appointed to the Supreme Constitutional Court. He was named head of the constitutional court in May, and took up that post just two days ago.

In some sense, then, Mansour is a member of the old guard, having served most of his career under the rule of Egypt’s previous president, Hosni Mubarak. And the constitutional court has clashed repeatedly with Morsi. Last November the president decreed himself sweeping powers that exempted many of his decisions, as well as those of the upper house of parliament and a constituent assembly convened to write a new constitution, from judicial review. The court temporarily quit work in protest, and in a ruling last month and another just yesterday, it invalidated his decrees.

But even under Mubarak, the court maintained an independent bent. In a column for Foreign Policy in 2009, Mark Lynch explained:

The Court, created in its current form in 1979, built a record in the 1980s and 1990s that earned it international attention for activism on several fronts, especially its willingness to take the vague human rights provisions of Egypt’s constitutional text and give them real meaning. The Court also took an assertive role in several hot political issues, such as the role of Islamic law and election administration. Its boldness had limits—it simply avoided the question of the use of military courts to try civilians, a tool the regime continues to use (probably in violation of the constitution) against the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Mubarak government cracked down on the court in the 2000s, however, curtailing its independence. It’s unclear exactly what Mansour’s beliefs are or how attached he is to the military, which has traditionally controlled the government. But given the court’s history, he is probably seen as a relatively neutral arbiter—at least, as neutral as it gets in Egypt these days.

Update: Here’s a photo from Mansour’s swearing in ceremony today.