The Tour de France has seen better days.

A spate of recent doping scandals in the cycling world has severely undercut the sport’s credibility, starting with the discovery of a French team’s rolling pharmacy in 1998’s Tour and culminating in Lance Armstrong’s televised admission to using performance enhancers. Either because of doping or the pitch of the recession, large international sponsors are becoming rarer at the Tour.

But in the long run, doping may not be the Tour de France’s biggest problem. Another looming—and arguably less fixable—threat to the world-class competition: climate change.

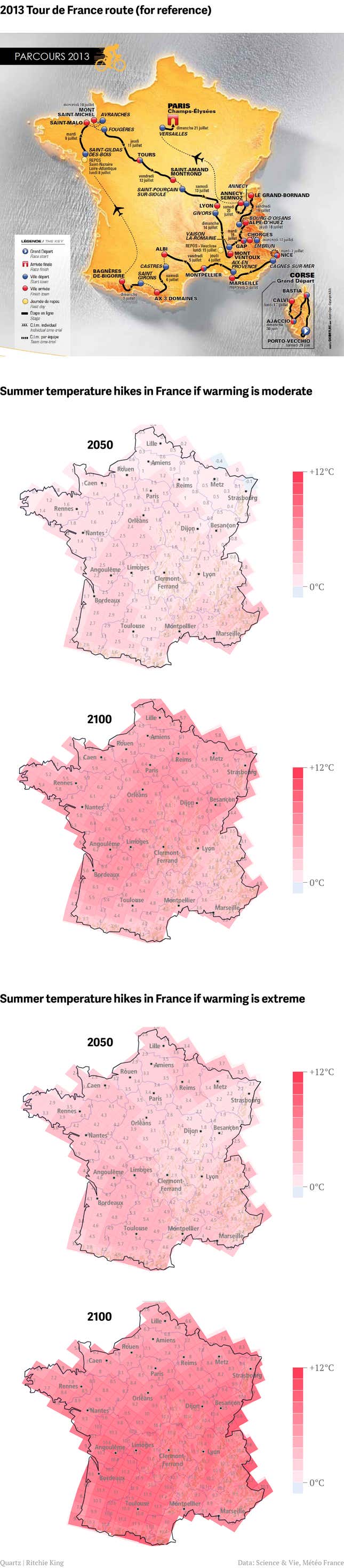

The maps above, taken from an online climate change simulator, show the change in temperatures expected for summers in France by 2050 and 2100. If warming is moderate, then temperatures in the south, where stages of the tour are often held, will increase by around 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit (two degrees Celsius) by 2050. If warming is extreme, then the increase will be closer to eight or nine degrees (roughly five degrees Celsius). The average high temperature for July in Toulouse, a southern city, is already in the low 80s; if it increased to the upper 80s or low 90s, that would be brutal for riders.

Extreme weather events associated with climate change are another issue; they’ve already impacted other high-profile races. This past May, riders in the Giro d’Italia, Italy’s equivalent to the Tour de France, endured abysmal conditions. In the early stages, scores of riders—including 2012 Tour de France winner Bradley Wiggins—crashed in torrential rainstorms. Later on, heavy snow forced the cancellation of a potentially decisive mountain stage and affected the outcomes of several others.

Rising temperatures and increasingly severe storms threaten the Tour de France more so than any other professional sporting event, snowsports aside. The Tour requires traversable roads at the highest Alpine passes and fan-friendly temperatures on the streets of Paris. Without those two conditions, the Tour cannot be both sufficiently challenging and commercially successful. And obviously, the race can’t be held in an air-conditioned dome, like a soccer match.

So, why not just move the Tour de France to June or September? Though it’s cycling’s biggest and most lucrative competition, the Tour is just one race in a full calendar that already stretches from February to October. Hold the race in June, and the Tour de France would leave teams with just days to recover from the similarly grueling Giro. Hold it in September and you would have to reschedule Spain’s Vuelta a España and the World Championships. Even if warmer weather allowed for racing later in the fall at lower altitudes, high mountain stages would remain unreliable. If climate change makes July unrideable, it’s not necessarily going to make November a viable alternative.