Yesterday, the mother of a suspected art thief claimed to have burned her son’s loot in a wood-burning sauna oven in Romania. Today, investigators have determined that evidence collected in that oven such as certain pigment residues, and pre-Industrial copper nails and tacks suggests Olga Dogaru destroyed at least some turn-of-the-century paintings.

The director of Romania’s National History Museum told the New York Times such destruction was “a barbarian crime against humanity.”

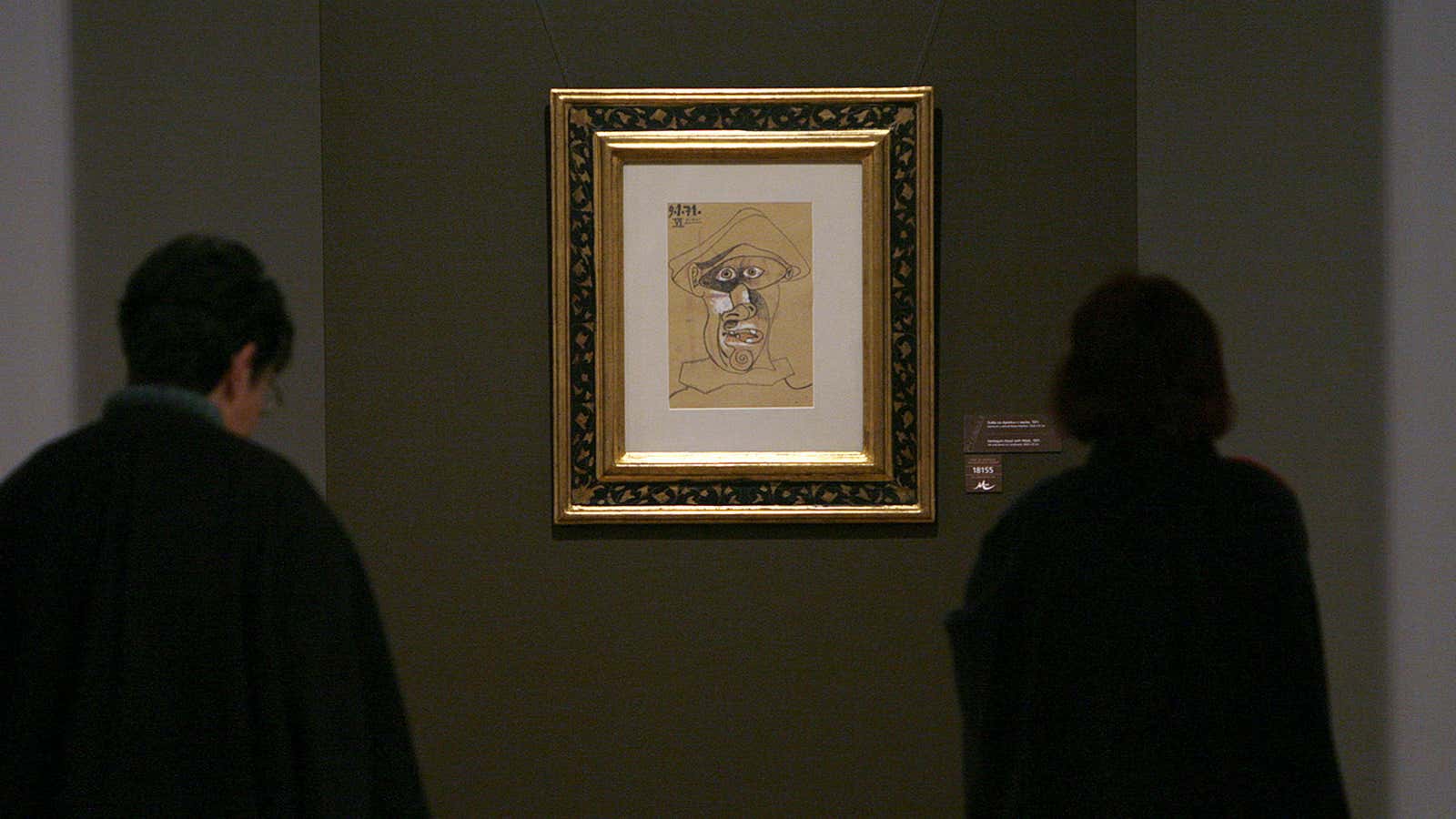

Equating the destruction of 5 paintings and 2 drawings–by Picasso, Monet, Gauguin, Matisse, Meyer de Haan and Lucian Freud–to systematic pillaging of civilian populations is beyond ridiculous. The impact of losing these pieces–especially in the age of the internet–is trivial. Works of art are not sacred objects.

While experiencing traditional works of art in person can by no means be replicated through reproduction, all of the works have at least some level of full-color visual documentation of their existence. Considering very few people would have ever seen any of these works in person in their lifetime and that most art history education is premised on studying reproductions of works in books, on screen, and in presentations, the primary impact of these works was not lost in a Romanian oven.

Works in the most popular exhibitions are only seen by a select few. In 2012, the most popular exhibition in the world, Masterpieces from the Mauritshuis at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, saw 10,573 visitors a day and less than 800,000 total, according to a survey by The Art Newspaper (pdf). The Louvre, the most-visited museum in the world, had 9.7 million visitors in 2012, only 0.14% of the world’s population. Yet the Mona Lisa is known the world over through its reproductions.

Printed and digital reproductions of the works will live on forever, just as other destroyed works have. Duchamp’s landmark “Fountain” was lost, yet it is a keystone in the teaching of Modern art. Any casual follower of art history knows the importance of this signed urinal even though the original has been destroyed. Three-hundred works by Rodin were destroyed when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, 2001, but hundreds more persist in museums, galleries, and private collections around the world.

Of course this is a tragedy for the owner of the works, the Triton Foundation, just as it is a tragedy for a homeowner to lose their home to fire or flood. (Though in this case it’s a homeowner with hundreds of homes.) It is less of a tragedy, but still unfortunate, to the future scholars who will not be able to travel across the world to handle, scan, and study these pieces for their research. Luckily, digital archiving allows for some continued study of the works.

Furthermore, none of these works are seminal masterpieces or by artists with small surviving collections. The world did not lose “Guernica” or “Water Lillies” or “The Vision of the Sermon.” Other works by these artists can be found in most western museums.

More people know these works now that they have been cremated. Their destruction has made them more famous and more widely seen than ever before. There is no need to mourn them.