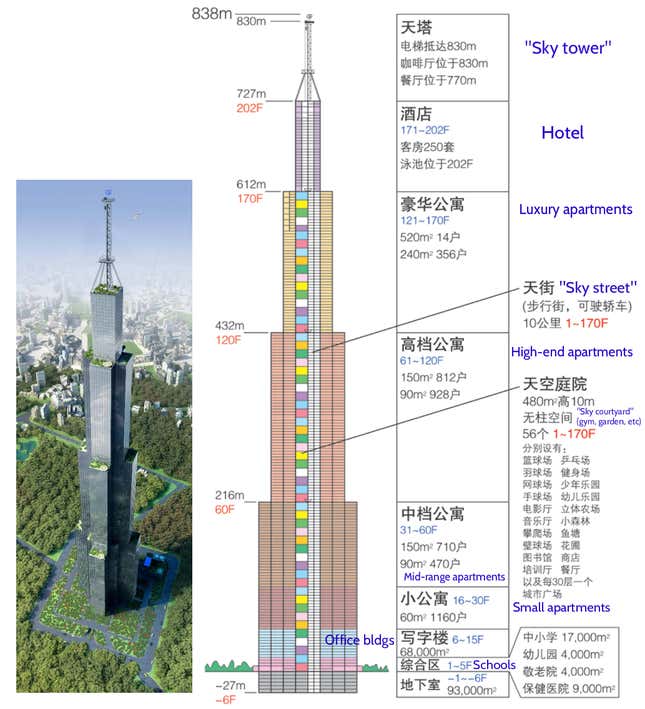

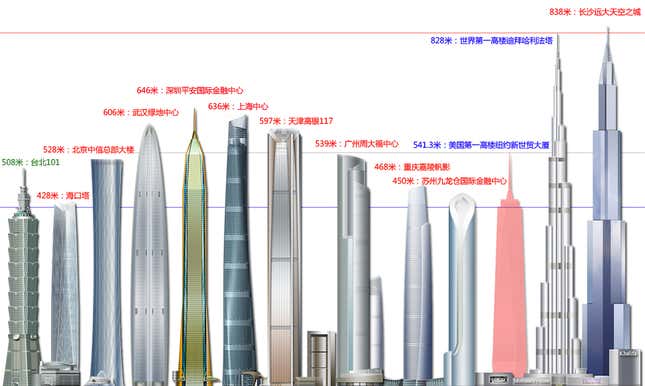

Construction on Sky City officially kicked off last weekend in Changsha, capital of Hunan province. Broad Group, which is building Sky City, is shooting for an April 2014 completion. By May or June, the 30,000 people it plans to accommodate (pdf) can start moving in. That also means that in the time it takes to gestate a human baby, Broad will finish a structure that hits 2,750 ft (838 meters)—ten meters higher than Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, the world’s current tallest building.

Broad seems confident it can pull this off. “We are the pioneers, the pioneers of men,” sings a chorus in hardhats on Broad’s website. “We are the geniuses, the geniuses of technology.”

Not everyone is so sure. It’s not clear that Broad Group can afford its $1.47 billion price tag, say Chinese critics, and constructing in such haste compromises safety. On top of that, there’s no actual need for Sky City.

Zhang Yue’s prefab revolution

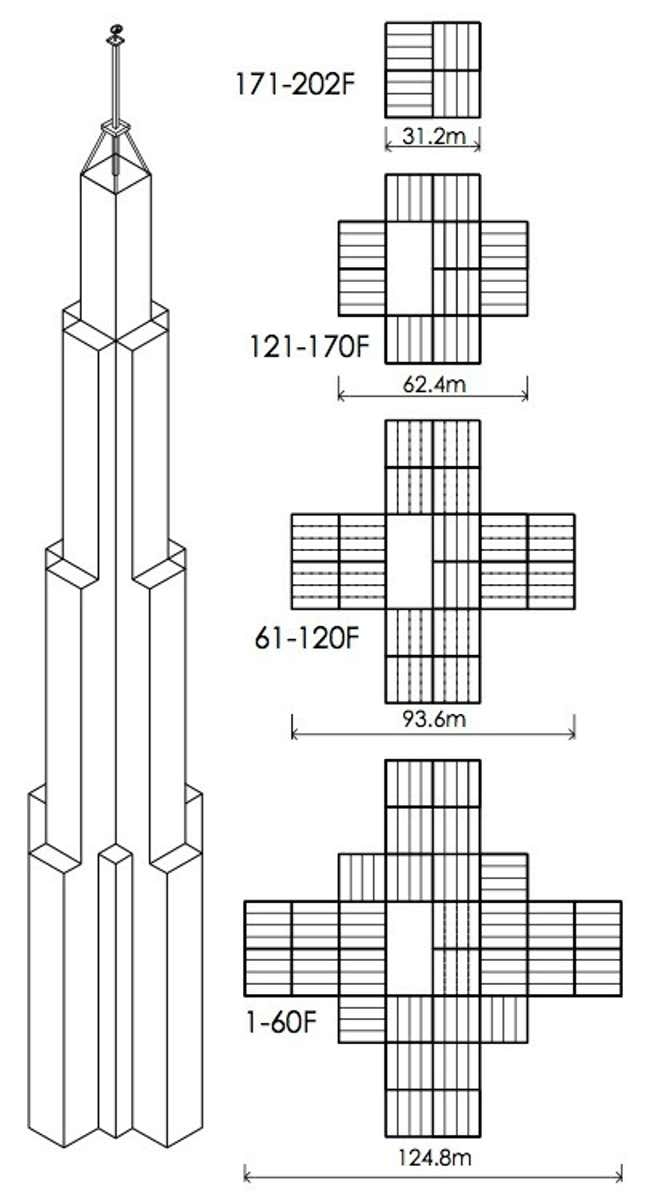

Zhang Yue, head of Broad Group and the brain behind Sky City, has made headlines for turning his mastery of factory production (he made a fortune in air conditioning manufacturing) toward feats of construction. Broad prefabricates each story offsite so that it can be transported for turnkey assembly in the last three or so months of the project. That means not just structure, but heating and plumbing, will be pre-made in a factory. While modular construction isn’t uncommon elsewhere in the world, no one has ever tried to build something on this scale.

Will $1.47 billion be enough?

What’s less well known is who’s going to pay Sky City’s $1.47 billion price tag. Though Broad Group boasts “mid-range costs“ (link in Chinese), that’s just slightly less than Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, which cost $1.5 billion (some estimate that the Dubai building cost billions more in total investment).

Chinese media report that Broad’s 2011 revenue was only $650 million. The investment is to be handled by Sky City Investment Corp, which has just $33 million yuan in registered capital (link in Chinese). Costs so far include the $64 million Broad paid for the property last November, and its $860 million contract with China Construction Fifth Engineering Bureau for infrastructure.

The city government, once skeptical of the project, is now gung ho, reports China Radio News, though provincial officials may be missing paperwork, reports Xinhua. While funding arrangements, if any, aren’t clear, an anonymous industry source told Hexun News that it’s likely that the local government is lending financial support (links in Chinese).

It’s also unclear how costly it will be to maintain the erected structure. ”It won’t be hard to build the skyscraper, but it will be difficult to operate it,” said Ren Zhiqiang, one of China’s leading real estate developers. Maintenance costs for residential homes can be steep; managing high-rise apartments typically cost three times as much as regular buildings, according to estimates cited by 21cn.com. And that’s not even taking into account the wear and tear on common spaces.

Sky City’s cash flow challenge

That strongly suggests that it’s going to need cash flow. But from where?

Burj Khalifa offers little guidance as it’s mainly office buildings and hotel rooms; Sky City will be 83% residential. Plus, an investment syndicate backed the project, and around 90% of salable space was sold early on.

Does anyone really need Sky City?

Places like Seoul or Hong Kong—cities with scarce space—might have use for Broad’s vertical utopia. But Changsha hardly exemplifies crippling urban density. And its 7-million population wouldn’t be enough to fill Sky City (link in Chinese), remarked Beijing Institute of Architectural Design head Wu Chen recently.

That’s particularly true since it’s out in the boonies. Sky City will be 9.3 miles (15km) outside Changsha’s outer ring road, pretty much smack dab in the middle of what used to be farmland.

And yet the structure will be a microcosm of urban life. In addition to apartments, Sky City will have office and hotel space, as well as schools, shops, recreational facilities, hospitals, gardens and community spaces. Although Sky City plans to pack in the amenities, many prospective residents will still have to commute to work. The building’s businesses will also need huge shipments of goods to feed, clothe and entertain the Sky City’s patrons and residents, which could lead to traffic jams.

The design of the apartments also sounds pretty unappealing. Pre-made construction of individual stories means units will have low ceilings and bulky walls, blocking natural light. This basically means Sky City will resemble “a giant stack of trailer homes,” as we put it before.

In that, Broad appears to be disregarding human scale and walling people off from their surroundings, both common features of Chinese urban planning. As one Changsha resident told 51dc.com, “If they finish it, I’d stay in the hotel, but living in a building that massive would be a little terrifying” (link in Chinese). Not all potential residents see it that way. “If the price is low enough, I’d consider trying it,” another Changsha resident said. “Eating, living, shopping all in one building—that could be really convenient.”

Tricky timing

With housing sales slowing, Changsha’s uptick in land sales will boost housing supply by early 2014. Broad Group’s dearth of experience in residential real estate (link in Chinese) and its ultra-speedy nine-month deadline both pressure to sell quickly—and if its lack of apparent investors continues, possibly at a loss.

Is it safe?

Those are good reasons for Broad Group to build on the cheap. But many are worried that will compromise safety. “There’s no precedent for this type of construction,” Yin Zhi, director of Tsinghua University’s School of Urban Planning and Design, told China National Radio (links in Chinese).

“This leaves only two possibilities: either this technology will stun the world with its brilliance,” Yin said. “Or it’s a sham.”

Broad Group’s lack of experience in erecting buildings of Sky City’s height is troubling. Sky City is more than six times taller than the tallest building Broad Group has ever made (a 30-story hotel in the Hunan city of Yueyang which it built in 15 days).

Materials are also an issue. The Burj Khalifa was made of aluminum, silicone and glass, as well as a foundation of concrete and steel. In order to be constructed pre-fab, Broad Group uses mainly steel.

And though prefabricating makes the building lighter in theory, that’s still incredibly heavy. Tsinghua’s Yin said that, from a structural standpoint, after 100 meters, building specifications have to change. Broad Group may know that—or it may not. ”Broad regards these as internal patents, so it has never released the technological details,” Yin told CNR. “So you can’t really judge [whether it’s safe].”

The company dismissed concerns about weight. “Anyone who has seen the schematics knows safety isn’t an issue,” said Zhang Yue. “This is a pyramid structure, and will be built using methods no different from the normal approach.”

Then there’s the speed issue. The Burj Khalifa took around six years to complete; Sky City will be done in nine months.

It’s not clear what the rush is, but its tight deadline could leave insufficient time for testing the structure. Lu Meng, the chief architect for Concord Century Holdings, told CNR that after every 12 to 13 stories, the layout of the heating and plumbing systems have to be switched around, and the foundation has to be reinforced (link in Chinese). “These things take time, and aren’t a matter of man triumphing over nature,” he says. “I think two years are more reasonable.”

Sky City bodes ill for the economy

Of course, Sky City could be a triumph, paving the way for fast, cheap, clean construction that will help China urbanize. But as is often noted, economist Andrew Lawrence years ago identified construction of the world’s tallest buildings as a turning point for an economy’s collapse.

Despite the country being riddled with ghost cities and empty shopping malls, dozens of skycrapers are being erected, fueled by vanity or politics or cheap capital. Currently, three 600-meter-plus projects are underway, while seven are in the planning stages.

Changsha’s Sky City is an example of the latest wave of building in China’s smaller cities, where local officials see big landmarks as ways to raise their cities’ profiles. Recent examples include the proposed 700-meter-plus Suzhou project, or a 400-meter skyscraper in Yinchuan, the sleepy capital of northwest China’s Ningxia, which Broad happens to be building.

Sky City will still be the tallest of these. Whether a symbol of China’s ambition or its excess, the building has a shot at becoming a monument to its moment in history. That’s not lost on Broad Group’s CEO, who in a recent interview invoked the Great Wall, the mammoth stone bulwark built by the Qin Emperor in BC 220 to protect against northern hordes. ”Compared with the Great Wall,” said Zhang (link in Chinese), “there is no essential difference.”