The budget impasse in Washington caused flight delays (until Congress fixed that) and cut million in funding for everything science research to pre-k teachers. Next up? The companies building spacecraft for NASA.

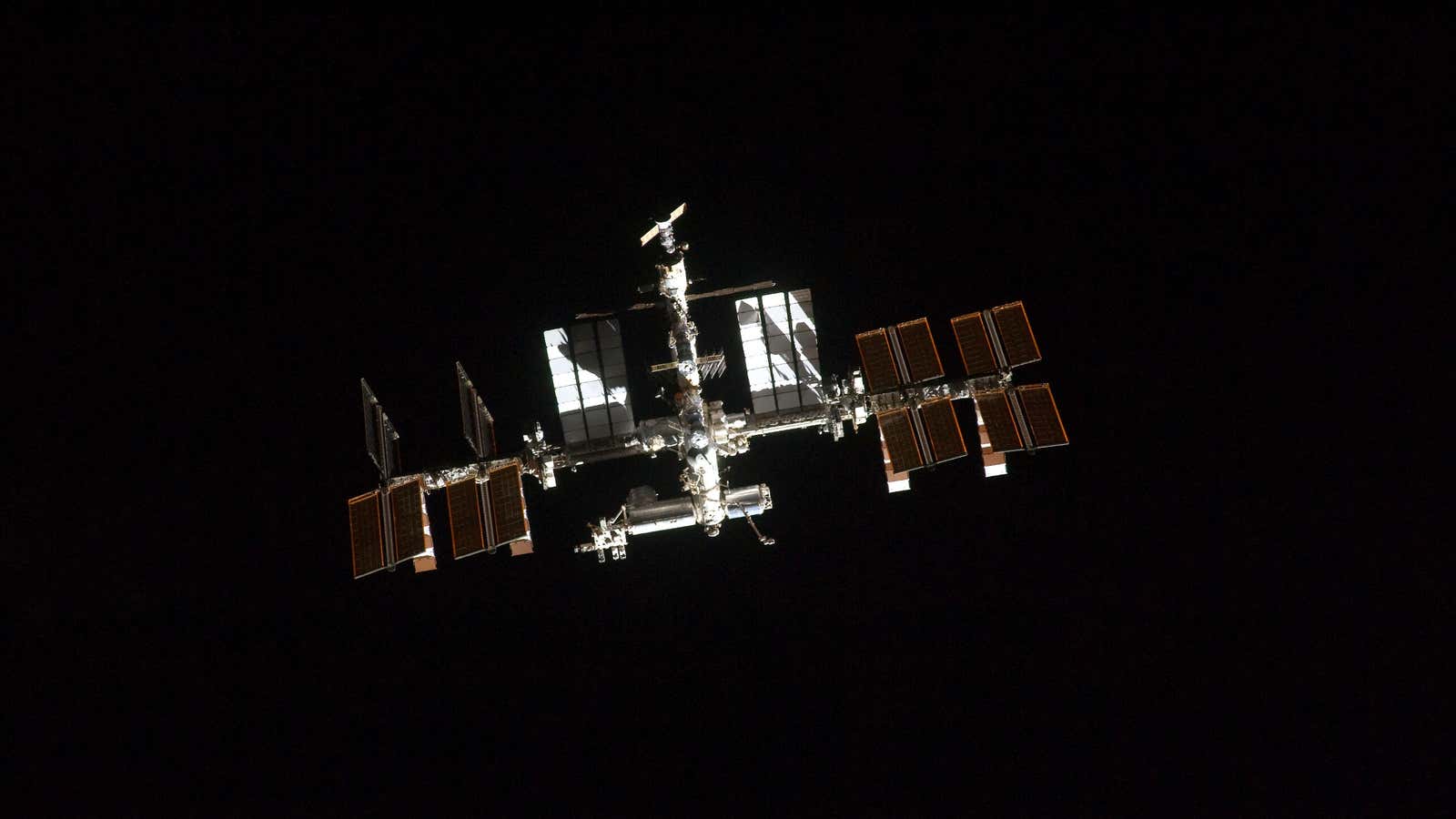

Boeing, SpaceX and Sierra Nevada Corporation are competing to build the replacement the Space Shuttle to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station; at least until 2017, those duties will be handled by Russia’s space program.

The US space agency wants $821 million to fund the development of these space craft next year; the best case scenario would give them $775 million, but it’s likely the agency will have to make do with $500 million. NASA says the sequester cuts ”jeopardize the success of the commercial crew program and ensure that we continue to outsource jobs to Russia.”

Why such a wide range of funding possibilities? Democrats in the Senate are assuming that across-the-board cuts imposed by budget sequestration will be alleviated by bipartisan deal-making, while the Republican House expects the cuts to stay in place. An agreement will need to be made before the new fiscal year begins in October, and it’s likely to result in funding on the lower end of the spectrum.

Currently, the three companies are working through a series of design reviews that ensure the space craft meet operational standards and are safe for crew, and each milestone unlocks more financing. With less money, those milestones get pushed back, possibly delaying the readiness of a spacecraft and forcing the US to stick with Russia or another contractor beyond 2017.

NASA could choose to live with the delays, cut one or two companies from the program earlier than expected to focus the funding, or ask the companies to pony up more private capital.

In the House, at least, there is a lot of skepticism of the program, which began under the Obama administration. Some lawmakers see it as a boondoggle akin to the loans made by the government to failed solar firm Solyndra. While those loans are usually paid back with interest, the money spent by NASA on private space craft is spent for good, and the resulting technology belongs to the company that designed it. Republicans would like to see companies pony up more capital themselves.

“It’s a big prize at the end of this competition,” one aide said, referring to the ISS ferry contract. “Put in more skin in the game to win that prize.”

There’s no public information showing how much private companies have invested in the commercial crew program alongside the government money: over the course of the program Boeing is due up to $460 million; Sierra Nevada Corporation $212 million; and SpaceX $440 million. None of the companies responded to requests for information about their investment.

Funding cuts could spell trouble for all three companies, but the firm with the most to lose is Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which is the most dependent on NASA. Boeing, of course, is a sprawling aerospace and defense contractor, and Sierra Nevada Corp. has a lucrative business manufacturing components for satellites and other space gear. However, Sierra Nevada’s bid was regarded as the weakest when NASA made the original award because of its unique technology, so it could be the first on the chopping block. SpaceX’s plan was seen as the fastest and cheapest because it is based on the technology that already delivers supplies to the ISS, while Boeing, which built the space station, offered a bid considered the most technically sound.

Earlier this week, Boeing unveiled a full-size mock-up of its vehicle, the CST-100: