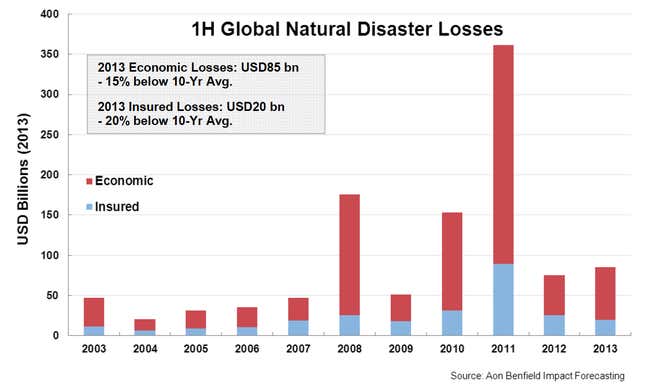

Wild weather has already taken an $85 billion toll on the world so far in 2013. Believe it or not, that’s actually a pretty typical sum for the first six months of the year. In fact, the tally of expensive disasters—that includes flooding in central Europe ($22 billion), a 6.6-magnitude earthquake in China’s Sichuan Province ($14 billion), tornadoes and other severe weather in the US ($4.5 billion from May 18-22 alone), and droughts in Brazil ($8.3 billion), China ($4.2 billion), and New Zealand ($1.6 billion)—is actually 15% lower than the 10-year average.

What’s unusual about 2013 is that many natural disasters struck places where people lack insurance. In fact, just 24% of the $85 billion in losses for the first half of 2013 were insured, according to new data released by Aon Benfield, a reinsurance advisory firm. Over the last 10 years, about 28% of disaster-related losses have been insured. Even in Europe, only 24%—$5.3 billion—in losses from flooding in May and June were actually insured.

This presents a huge money-making opportunity. Yes, insurance companies have to pay up when things get destroyed, but there’s also clearly a lot more money to be made in insurance premiums in under-insured regions.

What’s more, the business of doom is swiftly becoming an asset class of its own—and one that pension funds love. With yields low across the world and markets difficult for funds to play, insurance companies are seeing an uptick in demand for catastrophe bonds, the cuter industry lingo for which is “cat bonds.”

For example, the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) needed protection against storm surges. Instead of seeking out a private reinsurance company to pre-fund its commitment to insuring the MTA, earlier this month it issued cat bonds to the public through a subsidiary. The MTA ultimately raised $200 million in coverage for the next three years. Meanwhile, investors in its cat bonds got a debt security that’s not affected by Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and returns a higher yield than a lot of other investments they can make right now—4.5% in this case. (For more details on how this works, see our recent discussion of the mechanics of cat bonds here.)

With so much of the world underinsured—and with what certainly looks to be a steady rise in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather—there’s clearly lots to be made betting on calamity.