The auto industry has been one of the few truly bright spots in the US economy since the financial crisis.

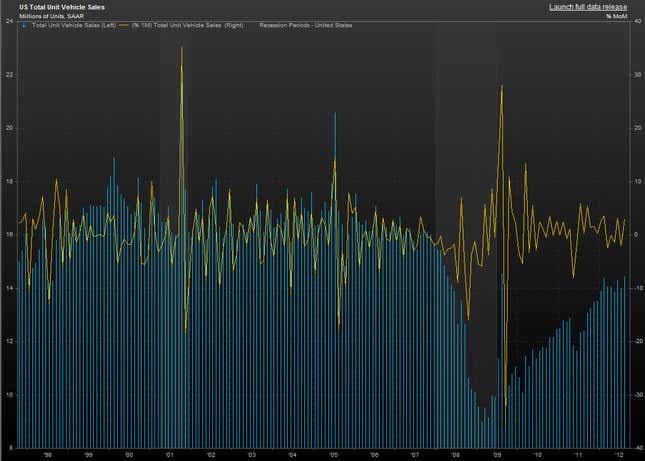

After a terrifying crater during the worst of the panic—albeit with a brief spike induced by the “cash-for-clunkers” program — car sales have crawled back to something like normal. And updates on auto sales from the big car makers Oct. 2 showed Ford Motor and Chrysler Group expect to sell cars at the fastest pace since the financial crisis struck. Good news, right?

Besides the general fear induced by the crisis, which prompted many to hold off on purchases of cars, a big reason why car sales collapsed was because the pipeline of cash to would-be car buyers was completely broken. Important players in channeling the money US consumers needed to buy cars, like GMAC—which had its roots as the in-house credit arm of General Motors but later got into mortgage-making and other lending—were tottering. Eventually, the US government launched an unprecedented intervention in the market, propping up both Chrysler and General Motors as well as their financing arms to the tune of $81 billion.

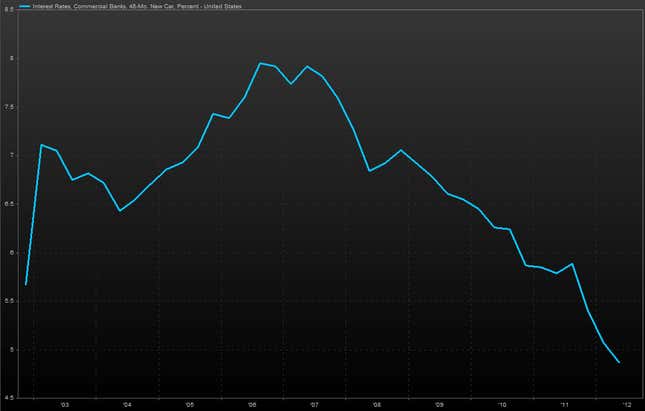

We’re in a much better position now. And thanks, in part, to the Federal Reserve’s efforts to keep interest rates low, rates for new car loans from banks are down to record lows. More good news, right?

And in an interesting development, cash is starting to flow from investors to car buyers with lower credit scores. More good news… right…?

If the idea of buyers with poor credit scores getting loans easily sounds familiar, that’s because it is. Yes, we’re talking about “subprime” again.

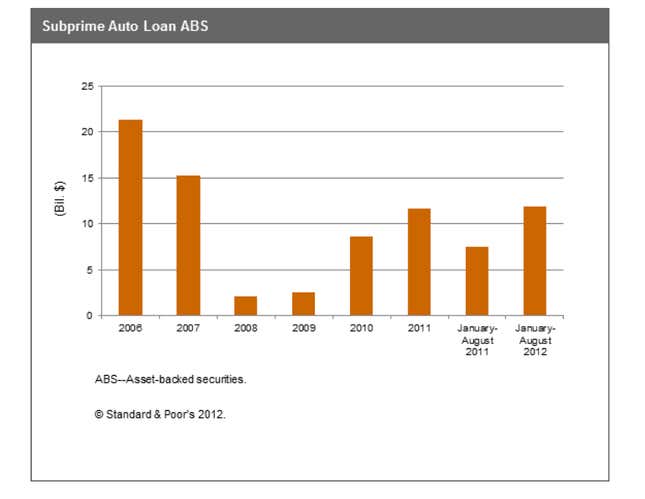

Global investors are desperate to find investments that pays them a decent rate of interest, or “yield.” Because subprime borrowers are riskier, the investments built around their loans do supply that higher yield. Increasingly, investors are liking the sound of that. And subprime auto bond deals have been picking up steam. Analysts at S&P think that some $15-17 billion could flow into new subprime auto bonds this year, up from $11.9 billion in 2011 and not too far off from the $15.3 billion seen in 2007, before the crisis struck.

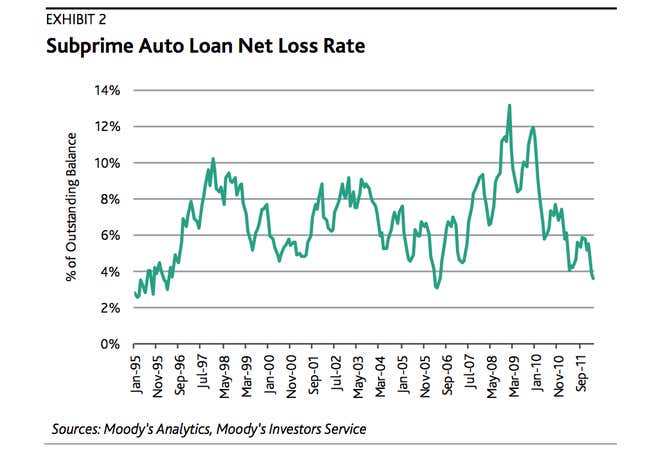

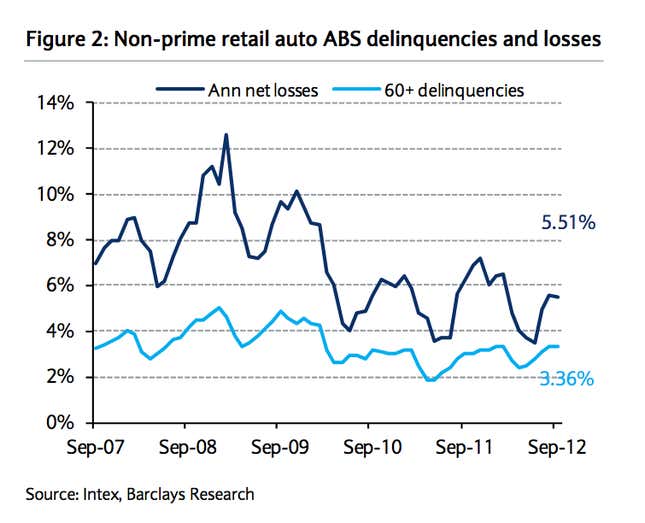

Part of the reason that investors are willing to buy subprime auto bonds—effectively lending money to higher-risk borrowers—is because the risk doesn’t seem too bad. The loss rate on these loans is down a lot from the pain investors felt back at the peak of the crisis.

Still, historically the pattern is that complacency about losses and competition between lenders leads them to make loans at interest rates that are too low to borrowers that are too risky. We’re already seeing the average credit scores and interest rates on subprime auto deals fall. And Barclays analysts have noticed that recently subprime auto loans have seen an uptick in loans going bad—although so far, at least, they don’t think it’s anything major to worry about.

Given that a significant chunk of the US car-buying public has credit scores that would put it in the subprime bucket — through mid-September it was 24.4% of used car sales and 11.5% of new vehicle sales went to subprime buyers—the fact that more and more cash is flowing through to those buyers is a good thing—at least for the short term.

But the auto industry is kind of like a microcosm of the US economy as a whole. Just getting the system moving again is the goal for now. But in the longer term the US has to do some real soul-searching about whether offering easy credit to riskier borrowers creates more problems than it is worth.