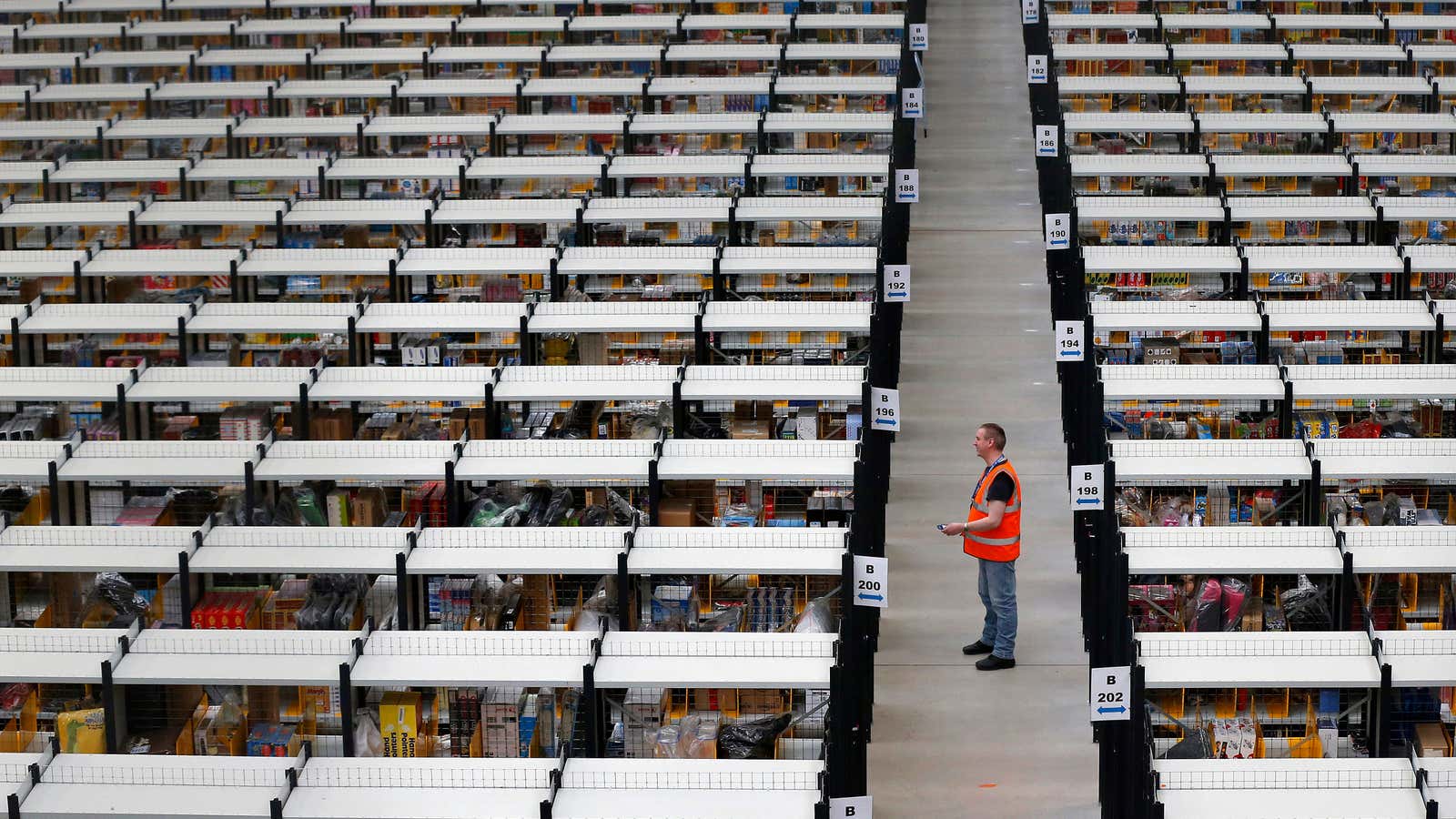

Will the middle class of the future spend its days scurrying around enormous, brightly lit warehouses in search of consumer goods?

Today, President Obama will visit an Amazon fulfillment warehouse in Tennessee as part of his efforts to talk about his preferred agenda of middle class jobs. Conveniently, Amazon announced that it will be hiring another 5,000 workers for these distribution centers, a move White House spokesman Josh Earnest described as ”certainly something that we want to encourage.”

But wait a minute—aren’t those jobs kind of crappy?

The gigs involve assembling the customers’ Amazon orders for delivery, and the company says the jobs pay about $11 an hour—not quite above the poverty line for a family of four. Amazon is careful to emphasize that the pay is better than traditional retail, which is to say, the smaller stores that Amazon and Wal-Mart have put out of business.

Many internet companies use fulfillment warehouses like these. The people who work there, called “pickers,” are often hired by sub-contracted staffing firms—a practice Amazon follows in the UK—which helps avoid workplace regulations for full-time workers. Journalist Mac McLelland got one of those jobs herself:

[W]e pickers speed-walk an average of 12 miles a day on cold concrete, and the twinge in my legs blurs into the heavy soreness in my feet that complements the pinch in my hips when I crouch to the floor—the pickers’ shelving runs from the floor to seven feet high or so—to retrieve an iPad protective case. iPad anti-glare protector. iPad one-hand grip-holder device. Thing that looks like a landline phone handset that plugs into your iPad so you can pretend that rather than talking via iPad you are talking on a phone. And dildos. Really, a staggering number of dildos. At breaks, some of my coworkers complain that they have to handle so many dildos. But it’s one of the few joys of my day. I’ve started cringing every time my scanner shows a code that means the item I need to pick is on the ground, which, in the course of a 10.5-hour shift—much less the mandatory 12-hour shifts everyone is slated to start working next week—is literally hundreds of times a day.

These warehouse jobs are better than unemployment, Pegatron, and perhaps mining, but they’re no replacement for the kinds of higher-paying factory jobs that used to form the backbone of the American middle class.

It’s an expression of the cold calculus of labor skills today: These are jobs intended for people without any college, unlike better paying technical employment or white collar gigs, and the wage premium is keenly felt.

Of course, not every tech company is hiring low-skilled labor in the US, but then again, not every tech company’s success is predicated on logistics that require a human touch. And Amazon, it is worth noting, brought a robotics company called Kiva last year to increase the use of automation in its fulfillment centers.

When the president arrives at Amazon’s Chattanooga facility, he will “focus on proposals to jumpstart private sector job growth and strengthen the manufacturing sector.” Listen closely to how he describes these jobs: Are the foundation of a stronger economy? Or are they a way to reduce the unemployment rolls by creating worse jobs?