In the next couple of days, South Americans could get a taste of Africa without even stepping on a plane. That’s because powerful winds over the continent are lifting up thousands of tons of dust from the Sahara Desert, and moving it 5,000-or-so miles over the Atlantic Ocean toward northern Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia and other places around the Caribbean Sea.

The great migration of desert granules is in fact a “quite common” occurrence, according to NOAA, raising the startling thought that the dust in our eyes on a windy day could’ve once been stuck in a camel’s foot pad. This most recent movement of grit is somewhat special, though, in that it’s much more concentrated than usual. By Friday and the weekend, it will be flying over South and Central America, with urban areas in its possible path including Caracas, Bogotá, Panama City, Port-au-Prince, and San Juan in Puerto Rico. The visualization above shows the possible track of the Saharan cloud, which in previous years has grown as big as the continental United States, based on one of NOAA’s aerosol models. (See where the massive sand blob is right now on this map.)

The plume of particulate matter goes by the tough-to-say-quickly, Bob Loblaw-like name of the “Saharan Air Layer.” Dry, dirty zephyrs typically begin to form over the Sahara in the late spring and summer, sending gusts of mineral-rich wind over the Atlantic once or twice a week. It’s not something that sailors are sucking in, as it hovers at a height of 5,000 to 20,000 feet. But it is something that pilots sometimes watch out for – although not as abrasive as volcanic dust, clouds of atmospheric sand can clog up a jet’s air filter and cause stalling.

What’s the floating dirt look like? A NOAA aircraft took this photo of the layer in September 2006 as it passed near Barbados (look for the whitish haze the clouds are rising from):

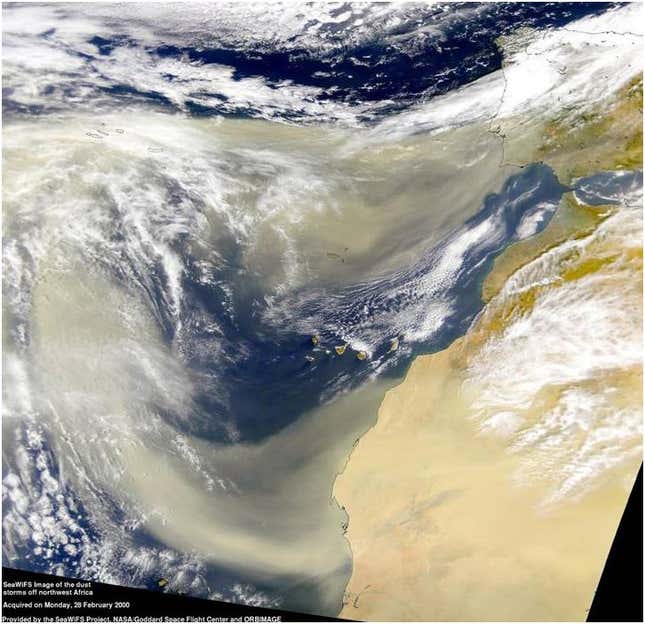

And this is the layer wafting off of western Africa in 2000:

As to where all this flying earth eventually winds up, some of it falls into the ocean and some comes down with the rain as far west as the Florida Keys. But don’t curse it the next time your mouth mysteriously feels full of sand: In a way that’s not totally understood by scientists, the layer seems to exert a weakening effect on hurricanes. Here’s are researchers from University of Wisconsin-Madison and elsewhere explaining it:

Scientists have discovered a correlation between hurricane activity in the Atlantic and thick clouds of dust that periodically rise from the Sahara Desert and blow off Africa’s northwest coast. They found that during periods of intense hurricane activity, dust was relatively scarce in the atmosphere, while in years when stronger dust storms rose up, fewer hurricanes swept across the Atlantic….

The researchers say that this makes sense, because dry, dust-ridden layers of air probably help to “dampen” brewing hurricanes, which need heat and moisture to fuel them. That effect, Velden adds, could also mean that dust storms have the potential to shift a hurricane’s direction further to the west, which means it would have a higher chance of hitting the United States and Caribbean islands.

On a side note, sometimes summer “sunsets in Puerto Rico are beautiful,” they say, “because of all the dust in the sky.”

John Metcalfe is a staff writer at The Atlantic Cities.

This originally appeared at The Atlantic Cities. More from our sister site:

A giant vortex of wildfire smoke is hovering over Russia

Practical lessons for turning around a neighborhood in decline