Max Levchin wants to talk to you about cervical mucus. The internet entrepreneur, who co-founded the now ubiquitous online payment service PayPal, has turned his focus to solving a problem he feels is more important than the hassle of entering credit card numbers: Infertility.

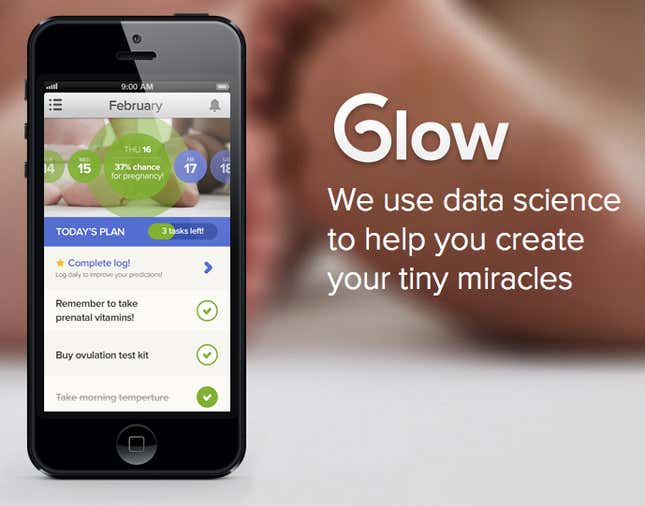

His new app, coming to Apple’s App Store next week, is called Glow—and through comprehensive data collection and analysis, it aims to help couples conceive naturally, or steer them towards the right medical help if they can’t. But Levchin wants the software to do more than just mark fertile days on a calendar: He wants to radically change the way American doctors and patients talk about infertility. Oh, and then he wants to turn the United States’ health insurance paradigm on its head.

Levchin and his cofounder, Mike Huang, realized that family planning could benefit from big data when Huang and his wife spent a year trying to conceive. “The issue is very dear to me,” Huang told Quartz, “Because I know the emotional roller-coaster is real.” Obstetricians, he said, aren’t equipped with much data on infertility. When a couple goes to their doctor saying they can’t conceive, he said, they’re often given an old-fashioned paper form to track ovulation, then told to come back in a few months.

Both men are cyclists in their spare time, and they saw that in the sporting world, people collect and analyze an enormous amount of personal data—part of the so-called “quantified self” movement. “You can become a total quantified-self junkie,” Levchin told Quartz. “Anything that can be measured, you record—and it’s applied to things like managing your weight, or deciding how likely you are to dope in the Tour de France. But with infertility? You get a Xerox from the 1960s.”

So they’ve created Glow to fill the gap. Levchin and Huang hope the free app, which has the same kinds of game-like features and simple design that make fitness junkies so app-happy, will make natural conception both easier and more fun. It gives its users daily prompts to enter data on everything from temperature to the sexual positions they’ve used. And it comes in his-and-hers versions, a choice intended to keep women from feeling that they’re alone in their efforts to conceive.

The goal is to help both current users and future infertility patients. By asking about sexual positions and female orgasms, for example, the app is collecting data on oft-cited but little-researched possible factors in successful conception. The founders say that physicians have already signed on to use this data in studies. And eventually, Levchin said, they hope to make the data collection totally passive (by using a combination of phone sensors and specialized hardware) so that you don’t even have to take the trouble of entering any numbers yourself.

A testing lab in your pocket

More and more health apps are being designed to turn big data into wellness hacks. The Scanadu, which recently broke the funding record on crowdfunding site Indiegogo and aims to have approval from the US Food and Drug Administration by 2015, measures a wide range of vital signs and churns them into diagnoses and suggestions. An app called uChek enables your phone to read testing strips usually analyzed on expensive lab equipment. And Asthmapolis uses a bluetooth-enabled inhaler to track asthma symptoms.

But Levchin thinks such apps are also baby steps towards a new way of maintaining (and paying for) personal health. ”Health-care and insurance are nominally data driven,” he said, “so it’s remarkable to me that something so data-dependent, in which we have the best resources available to look at the data, is so broken. The costs of health-care are skyrocketing, and costs go up exponentially when you delay care.” With vitals constantly tracked and analyzed, patients could be warned to see a doctor early. Glow, for example, responds to reports of pain during intercourse or excessive cramping during periods with a suggestion that women get screened for endometriosis, a disorder that can cause fertility issues. Most women reporting pain won’t have the disorder, but an early screening makes it easier for doctors to remedy the problem if they do.

But the current American insurance system, Levchin said, rewards “self-willed lack of knowledge” by making patients afraid of discovering pre-existing conditions that could raise their premiums. So for big data apps to fulfill their potential, insurance companies would have to accept that early detection is better than benign neglect.

The state of US health insurance is especially troubling for fertility problems, Levchin said, where treatment is often considered an elective (i.e., not medically essential, and hence not eligible for insurance). But they have some ideas for dodging the financial trap some couples face.

Users can opt for a service called Glow First, which charges $50 USD a month for 10 months. If a couple can’t conceive during that time, they’re given an equal split with others in their monthly pool. The couples who did manage to conceive cede their money as a donation for the others to get treatment. To make sure there’s enough money for Glow First’s early users, Levchin is seeding the fund with $1 million of his own money. “I will personally fund a bunch of babies,” he said, “and if nothing else succeeds, I don’t see how I can be too disappointed with that.”

The key measure of Glow’s success, Levchin and Huang said, will be the number of babies born on its regimen—and they’re already receiving pictures of positive pregnancy tests from the 250 women in their beta group. But after that, it will be measured in the number of dollars saved that couples would otherwise have had to pay themselves.

And once they’ve made conception cheaper and less taboo for research and discussion in the US, they’ll branch out in other ways: To developing countries, where fertility issues get even less attention, and then on to other medical problems that could benefit from data collection. “The ultimate goal,” Levchin said, “Is to go after the overall state of health-care costs in this country.” But for now he says he’ll be satisfied with a spike in boys named Max and Mike.