The next Ernest Hemingway might not craft his masterpiece online. He might still publish some futuristic form of a book, and his works will be printed in publications—digital or print. Still, people will want more from a literary hero. He’ll probably have online accounts—Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, new social networks as yet uninvented—and chances are that he’ll use them not only to promote his books, but to document his personal life. Over the years, he’ll compile a lifetime’s worth of photos, videos, sarcastic status updates, random blog posts, interesting links, and messages to friends.

When he dies, his fans will continue to search voraciously for any unpublished work. In the past, the author might have left behind letters, drafts, scribbles, business documents, pictures, even receipts and bank statements. These would remain boons to his kin, becoming part of the estate and generating income well after the author’s death. A birthday card sent from John F. Kennedy Jr. to his father sold for $17,000. The original Hemingway’s mother compiled scrapbooks full of pictures, letters and drawings during his youth, in his case gifted to the JFK Presidential Library and Museum upon his suicide.

But in the modern world, these records reside not in the dusty attic of the family home but in the air-conditioned climate of a server farm belonging to a technology giant. So how can an estate get them? What if they don’t have the deceased’s password? Who owns the rights to the content?

The answers to these questions are vague, particularly when the deceased don’t plan ahead. And it’s an even more complicated problem when the account and the data stored in it have commercial value. For the heirs of Hemingway II, those status updates, notes, pictures, friends lists, and even links shared could prove a veritable goldmine… if that is, they can get them.

Nearly all major social media companies have already been embroiled in some kind of dispute about deceased users’ accounts. We’ve chosen to focus on Facebook because it’s so ubiquitous, because people post so much of their lives to it, and because the company, perhaps more than others, has challenged the idea that a dead person’s heirs own the rights to her digital property.

What’s in a copyright?

Part of the difficulty stems from the ambiguity of what the end-user license agreement (EULA), the basic contract you agree to when you sign up, grants a company. Different social media companies have different ways of handling users’ accounts after their deaths, and are held to different legal codes based on where the users are. Most will disable accounts at the requests of a person’s estate, though will sometimes allow the family to download emails and pictures first.

When Facebook, for instance, receives notice of a user’s death—either from his estate or from a third party with documentation—it typically turns her active account into a memorial, where friends can leave messages or see posts. The account itself, however, will be shut down to active use. No one—including relatives—can log in to a memorialized account, but Facebook friends can leave messages on the page, and all the data in the account continues to float about somewhere on Facebook’s servers.

Good news (for the estate at least) is that Facebook can’t simply turn around and publish a book full of a dead user’s content without the estate’s permission. By signing the EULA users give Facebook a broad license to store—but not distribute—a copy of their content; but Facebook acknowledges that users “own all of the content and information [they] post.” This works just like old-fashioned letters and notes that you might find tucked away in an attic.

Copyrights don’t die with the author; if not already sold, they automatically pass on to his heirs. But despite owning the copyright the next Hemingway’s estate might not be able to get an actual copy of his data without making a serious (and costly) stink.

Social media companies don’t like to give out user data to other people (evidently, the government gets a pass), and use a variety of laws to avoid doing so. A few US states have adopted laws governing digital content, but even they fall short; some only apply to minors, others apply only to email, and more still don’t discuss user-generated content at all. Social media companies have argued that the outdated 1986 Stored Communications Act prohibits them from disclosing personal information—even from the account of a dead person—without a court order.

Under Facebook’s current policy, the executor of a will can request a copy of the content in a deceased person’s account with proper documentation. But, Facebook says, they’re not guaranteed to receive it, even with a court order. A form on Facebook’s webpage states (our emphasis):

Please note that submitting [a legal document proving inheritance and a court order] will not guarantee that we will be able to provide you with account content. We take our responsibility to protect the privacy of people who use Facebook very seriously. If we determine that we cannot provide the content, we will not be able to share further details about the account or discuss our decision.

Estate beats Facebook—if it fights hard enough

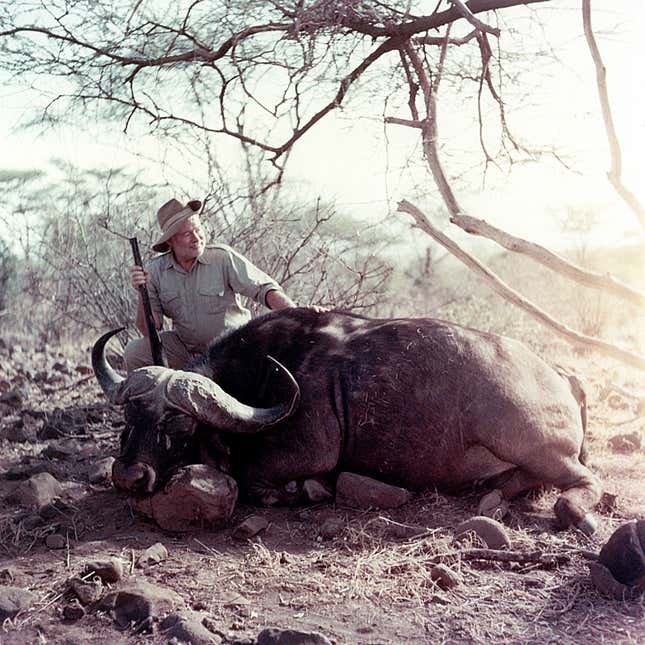

Facebook at times resisted giving out information to a dead person’s family, particularly when the deceased didn’t leave a will requesting it. Take the case of Benjamin Stassen, a 21-year-old who, in 2010, committed suicide without leaving a note. (For what it’s worth Hemingway, though 61 at the time, did the same.)

Wanting answers, his parents, Jay and Helen Stassen—Jay happened to be a lawyer—obtained court orders demanding that Facebook and Google hand over a copy of their son’s content. Google complied immediately; Facebook did not.

After weeks with no response from Facebook, the frustrated couple agreed to appear on Rock Center with Brian Williams, a NBC prime-time news program in the US. Days after the program aired, a lawyer representing Facebook got in touch to tell the Stassens there was no way that Facebook would hand over their son’s content, although they legally stood to inherit his property.

What followed, the family says, was a legal nightmare that lasted for months. Facebook wanted them to sign extensive indemnification agreements that would put the family at risk for massive losses. They initially refused. ”We were thinking: that’s wrong, that’s just wrong,” Jay Stassen told Quartz in a phone interview. “[The terms of those agreements] were really inappropriate.”

Despite the emotional toll, they pressed ahead, and threatened to hold Facebook in contempt of court for failing to comply with the court order. The company finally agreed to give the Stassens their son’s content—so long as they agreed never to disclose the information in the account to third parties. They agreed, though not without reservations. ”What if Benjamin had some fabulous poem on there and we weren’t able to share it with the world?” Helen Stassen says. But they couldn’t face a further battle.

They also count themselves lucky to have gotten a copy of Benjamin’s content at all. “Most people will never be able to do what we were able to do. We could prevail because we are educated, we had means, we had tenacity… and Jay is a lawyer,” Helen says.

Facebook declined to comment on why it accepts or rejects content requests from heirs of a deceased user. It also declined to tell us the form this content takes when—if ever—a content request is accepted.

Lawyers we spoke to unanimously agreed that the estate not only owns the material in the account, it has every right to a copy of it, if not the account itself (more on that shortly). The copyright is the property of the author and his estate, and if families press their case, the estate will win.

But companies enjoy an advantage of size. “Facebook is obviously a lot better financed and a lot better able to take a lawsuit on for a few years and take a loss on it than the family of a poor bereaved person,” says Robert Clarida, Partner at Reitler Kailas & Rosenblatt LLC and adjunct professor at Columbia Law School. A company can drag out the process by, for instance, insisting that the case be heard in another US state, or challenging the estate’s claim.

The estate of Hemingway II could face a similar legal battle. And with money at stake, social media companies could have that much more incentive to drag it out.

Whose account is it anyway?

Yet even if Hemingway II’s heirs win the copyright case, they won’t be able to log into his account—not legally, anyway.

The estate might want to continue using an account to promote the author’s works after his death, or for some other purpose. Hemingway II may have signed up for a personal account as a six-year-old, and it may have taken on commercial value over the course of his life.

But EULAs like Facebook’s restrict use of a personal account to one person and one person only. ”We do not make special exceptions or grant access privileges to anyone who may have had access prior to memorialization or wishes to have access after memorialization,” Facebook spokesman Brandon Lepow said in an email.

Facebook’s policy has not yet faced a significant legal challenge. ”In general contracts are enforceable if they are really legitimate binding contracts,” says Clarida. But the lack of case law still means the status quo might change.

There are also likely to be different standards around the world. For example, when you buy books or games online, you’re typically buying a non-transferable license to that content. When you die, your heirs aren’t entitled to that license. The EU last year upset these standards however, decreeing that digital game publishers can’t stop your from reselling your digital games (so long as stop using them yourself). That’s because it found that “the making available by [a company] of a copy of its computer program and the entering into of a license for an unlimited period in return for payment involves a transfer of ownership that constitutes a ‘sale;'” just the same as if a user were buying that software on a CD, lawyers of Goodwin Procter wrote in a memo. The EU decision therefore questioned the idea that internet property can be non-transferable. This, however, is not the way US courts see the matter.

It’s probable that Facebook will face a similar kind of challenge over ownership or transferability of its accounts. ”There are definitely going to be more suits about this,” Clarida says. ”Courts are really going to start having to take [social media] more seriously. People are running business through Facebook apps and there’s a lot of commercial value in the stuff that people are posting. It’s not just people talking to their friends.”

Posthumous fame

In any case, Facebook—like other social media companies—has a hard time enforcing the policy of shutting heirs out of a dead person’s account. So long as Facebook does not receive notification of a user’s death, friends and family of the deceased could very well keep the account active if they have access to his password, and even if it violates Facebook’s terms of service.

Maurice Ross, an intellectual property lawyer for Barton Esq., says that his clients who have planned ahead have been able to continue operating both the personal and public pages of deceased family members. ”If I was doing estate planning for a famous author, a critical thing would be that somebody’s got the information,” he told Quartz in an interview. “One of the things that’s important is that the executor take charge of the account very quickly.” Legal experts advise clients to record passwords in their wills or on online apps like SecureSafe or Assets In Order.

Hemingway, possibly beset by mental illness, had plenty of time to put his affairs in order before he committed suicide in his Idaho home. We certainly hope the next great author lives a full life and dies in his sleep with a notarized will in his safety deposit box, but we also hope he prepares for the worst. And what of the author who finds fame only after death?

“Most people aren’t thinking about it unless they’re already making money in it,” says lawyer Amy Holzman, the head of trusts and estates for Barton Esq. ”Most people are going to think about where to put their stuff and their valuable assets, but they don’t think about their intellectual property assets.”

Because the internet is so young, there aren’t many rules for what happens to the lives people live online. Clearly formalizing those rules is going to take time and years of legal action. So in the lawless digital land it pays to think ahead—even if you haven’t inherited Hemingway’s literary talents.