OKAWVILLE, Illinois—This summer’s drought and blistering heat in the American interior have affected crop yields dramatically. The US Department of Agriculture recently revised its corn harvest estimates downward by 52 million bushels, as farmers across the midwest rushed to harvest weeks early, hoping to salvage stunted plants.

Despite popular attention to the beleaugered farmer, most purchase federally-subsidized crop insurance. As many as 90 percent of farmers are financially insulated from effects of the drought. But other players in the agricultural economy won’t be so lucky. Grain merchandisers–who operate the iconic grain elevators that dot the American Midwest–are suffering the effects of a poor harvest in soybeans and feed corn, especially.

Top Ag, Inc., an agricultural cooperative based in Okawville, Illinois is harvesting about one-third of a normal year’s crop.

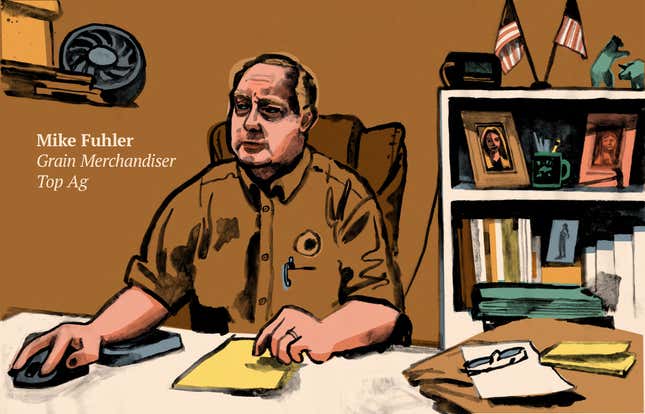

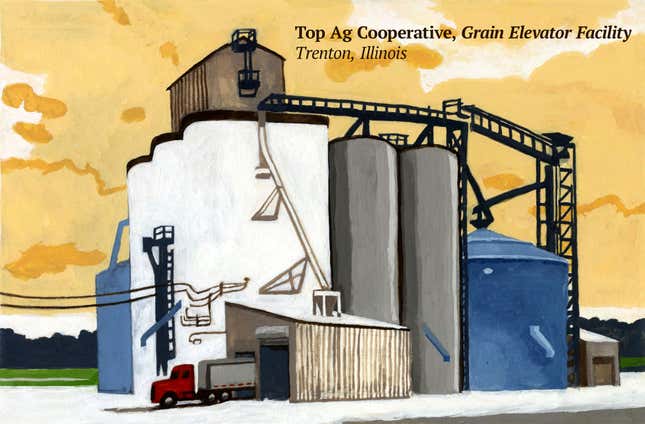

Top Ag operates seven storage and processing facilities in five counties east of St. Louis. Mike Fuhler runs the grain department at the Trenton, Illinois, location. The Trenton elevator receives feed corn from surrounding farms. “Yields are way down,” says Fuhler. “In good years, you see corn yields as high as 190 to 210 bushels an acre. Now, we’re seeing an average of about 70 bushels, with some areas producing 30 to 40.”

“This time of year we might expect to have a line of trucks waiting to deliver feed corn.” There is no line. Over the course of two hours, a single producer delivered a crop. Corn rushed from the belly of the truck into a subterranean pit, then was hauled by mechanical buckets to the top of the top of the elevator. Top Ag purchases the grain and resells it. About a third of it goes to river terminals on the Missisippi, for export. The rest is shipped by truck and rail domestically.

Top Ag is finishing off a huge new metal bin with a significantly faster elevator at the Trenton location. It might help at peak moments in future harvests, but it won’t do much this year.

Scorched plants line local fields. Stalks are thin and gray-brown. Traumatized by lack of moisture, many plants have failed to produce even a single ear. Others bore one, but no more. And a scraggly lot they are. “A healthy ear of corn will have 29 or 30 rows on it. These,” he says, yanking and twisting one off, “maybe have eight or nine.” He pulls back the husk to reveal a stunted miniature, dotted with wayward kernels. “If that.”

The Trenton elevator handled 285,000 bushels of corn last year. Fuhler expects this harvest to top out at 120,000 to 130,000 bushels. Which suggests a mystery: if yields are down by two-thirds, how could deliveries be down by half?

“Quality,” he says. On Labor Day weekend, the midwest was doused by the remnants of Hurricane Isaac. The late rain may have saved the soybean harvest, but only made the corn worse. Hot dry conditions followed by heavy rain are custom made for growing Aflatoxin, a ruinous fungus. Sure enough, local fields and farmers’ bins are full of it.

Any crop with more than 20 parts per billion of Aflatoxin is unfit for human consumption, as well as for lactating dairy cows. So local farmers are delivering all of their corn crop to the Trenton facility, before the fungus gets any worse in their bins.

Now all Top Ag deliveries are being tested for Aflatoxin. Fuhler operates a table top chemistry lab to determine contamination levels. He’ll take deliveries at over 20 ppb, but keeps them segregated. The Cargill plant at the river rejects anything over 20 ppb outright. Fifty-seven percent of corn deliveries to Trenton have topped out above the 20 ppb threshold since the beginning of the harvest.

The business consequences for the Top Ag Co-op are still unfolding. None of the 24 people who work for the company in Trenton have been laid off. The Trenton trucking department is scrambling for outside hauling work. Deliveries that would have been spread out over the coming winter will be greatly reduced, so grain warehousing will take a hit, too. The agronomy department—which sells fertilizer and chemicals, as well as application services—should be unaffected. “We’ll just do our best, and see how it goes from here,” shrugs Fuhler.