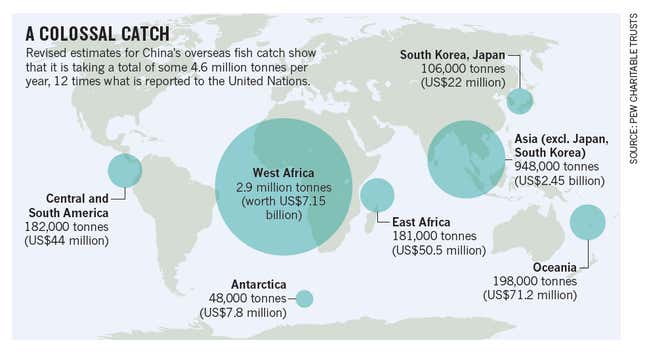

China’s fishing vessels dominate the planet’s seas—in fact, it has the biggest distant-water fleet in the world. That fleet is pulling in an estimated 4.6 million tonnes (5.1 million tons) of fish, worth around $10 billion annually, though it reports catching around 12 times less than that. Tuna’s a big chunk of it, given its value (a Pacific bluefin tuna went for $1.76 million at a January auction in Tokyo). The pricey fish made up an estimated 15% of its total catch (pdf, p.3), by volume, in 2010.

But even as the world’s tuna supply has grown scarcer, China has ramped up its fishing fleet in the South Pacific, now 1,300 boats strong, says the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), most of them in pursuit of tuna. What’s more, Chinese fishing boats there are getting an unfair advantage—$7.05 million in subsidies, including $1.7 million for diesel fuel, Charles Hufflet, head of the Pacific Tuna Industry Association (PTIA), told ABC. “[W]ithout that subsidy [China Overseas Fishing Company (COFC)] simply could not exist in the Pacific fishery at all.”

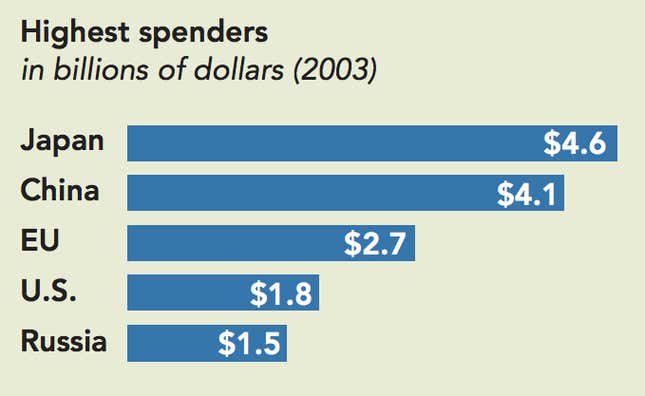

Where does that $4.1 billion go?

The target of Hufflet’s ire, COFC, is a Shenzhen-listed subsidiary of Chinese National Fisheries Corporation (CNFC). A massive state-owned enterprise, CNFC’s operations span the globe, and it’s licensed to export to the United States, European Union, Japan and other major fish markets (pdf, p.40). Despite its size, CNFC itself makes up only about one-third of China’s deep-water fleet (the rest is non-state smaller regional and coastal Chinese companies). In addition to CNFC’s subsidiary operations, other state-owned enterprises tend to dominate China’s global tuna-fishing industry (pdf, p.92).

And those state-owned firms are the chief beneficiaries of considerable state largesse. After Japan, China is the biggest subsidizer of its fishing fleet (pdf, p.220), spending about $4.1 billion a year, by the latest calculation. Here’s how China stacks up:

The southern Pacific’s albacore population is shrinking

Here’s why this is a problem for everyone else. There are fewer and fewer albacore tuna in the fishery in question, which covers Hawaii, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the US Pacific Islands. In fact, the global tuna regulator deems the area “likely to be overfished” (pdf). That means it takes more labor and fuel to land each tuna. And Chinese government subsidies offset those rising costs, making it difficult for fishermen from other countries to compete.

Rising costs are hitting China’s fishing industry

Smaller Chinese fishermen who don’t benefit from state support are suffering as well. Rising costs of fuel and labor are pushing an estimated 80% of them out of business.

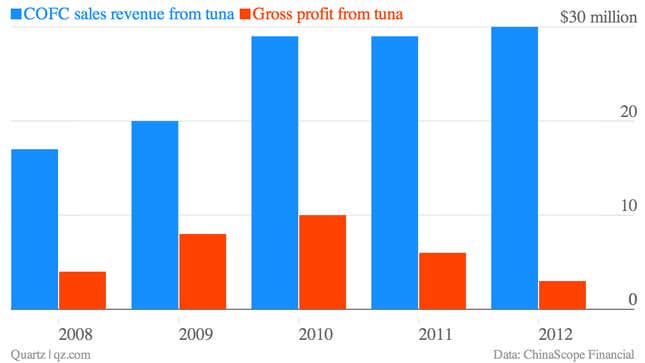

But even those that the government does prop up are struggling. COFC is a case in point. The profits from catching tuna, which made up about 38% of COFC’s 2012 revenue, are clearly falling, via ChinaScope Financial data:

And that’s with subsidies. In the first half of last year, COFC received $7.8 million from the government, allowing it to to claim $3.0 million in profits for that period. For the first half of this year, with $5.35 million in subsidies, COFC projects a net loss of $2.1 million.

This isn’t exactly new—it’s just that the company hasn’t been so transparent before. But as Tabitha Grace Mallory, an expert on China’s deep-water fleet, told the US Congress last year, the subsidies in the form of tax cuts and fuel offsets to CNFC have risen sharply since 2006, making up around half of the company’s net profit by 2008 (pdf, p.4).

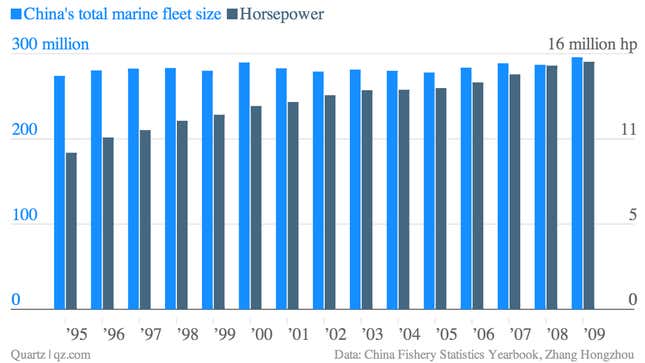

Investing in a marine powerhouse—literally

Like Hufflet, Mallory concludes that “without such subsidies, it is doubtful that China‘s DWF [deep-water fishing] industry would remain profitable.” The diesel subsidy is particularly helpful here; it defrays the costs of traveling farther than competitors. This matters more and more as China’s fleet adds large industrial fishing vessels, which enjoy a big competitive advantage over small boats, explains Daniel Pauly, a scientist at the University of British Columbia.

“The fishing they do comes from the powerful engine that drags [nets] behind the boat, whereas with artisanal fishermen… the fish that they catch come from their own input,” Pauly tells Quartz. “Industrial fishing is much more profitable. The returns to capital are much bigger, [as are] the returns to labor.”

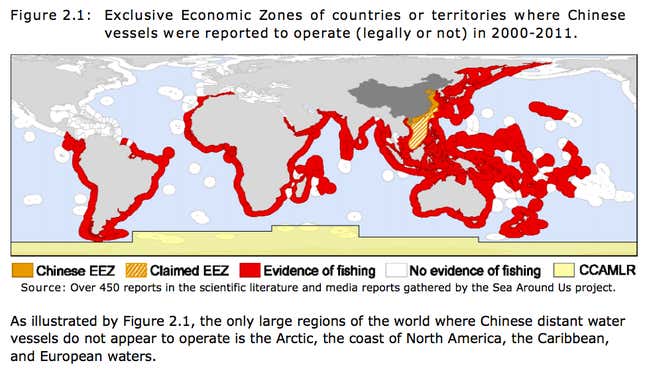

“Grabbing the high seas and EEZs with both hands”

The explicit rationale of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) here is expansion. China’s latest five-year plan aims to put 2,300 official vessels to sea—300 more than today—by 2015. That would up reported output to 1.7 million tons, or about $2.6 billion, a 51% increase. If the real catch increases by the same proportion that’ll be a lot, considering that China’s deep-water fleet already takes in around 10% of the global deep water catch, according to a recent paper given at the EU Parliament.

This expansion appears already to be under way. Even as China recently volunteered to slash its tuna-fishing fleet by 10%, COFC, at least, is expanding. It recently proclaimed on its website that the completion of six new vessels “further solidifies our leading position in Fiji’s tuna industry” (link in Chinese). Tax incentives to shipyards are another form of subsidy—one probably not counted in CFOC’s mid-year report—that help Chinese fishing vessels, as the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency explains in this report (pdf, p.92).

However, this strategy has been championed for a while now. The last five-year plan (2006-10) determined that China’s fleet should “grab the high seas and EEZs with both hands, and turn these two wheels in synch” (pdf, p.103), says Mallory. (“EEZs” refers to exclusive economic zones, territorial waters off the coast of a given country. Because fish tend to congregate closer to shore, fishing typically takes place in EEZs.)

The old “developing country” defense

Against charges that subsidies promote overfishing, the Chinese government argues that they’re the right of a “developing country” (pdf, p.15), even as its aggressive illegal fishing practices threaten the livelihoods of Indian, West African and, in the current context, the fishermen of Fiji and other Pacific Islands.

But why is the Chinese government spending $4.1 billion on “grabbing” those “wheels”?

Without government support in catching fish in other countries’ EEZs, many Chinese fishing companies would go bust. Industrial development and land reclamation have left China’s coastal waters virtually uninhabitable to fish. A 2009 inspection revealed that factories were spewing 14 million tons of heavy metals into its seas, degrading the ecosystem and crippling China’s inshore fishing industry. On top of that, lax fishing policies even in home waters and the use of fish detecting devices mean Chinese fishermen long ago stripped their own coastal waters clean of fish.

“About 10 years ago when you put a bucket into the sea, you could probably catch three fish. Five years ago, you could catch maybe one or two,” one fishing-boat owner told the China Daily. “Now you barely stand a chance of catching any.”