The state of Detroit public pensions is a very sad situation. I was recently on a panel with a Detroit fireman named Dennis, who spent his career at a dangerous job and made large contributions to his pension. He doesn’t have Social Security; his pension is all he has. Not surprisingly, he’s fighting to keep his benefits from being cut. He’s not alone. Now the city of Chicago is coming to grips with its underfunded pension and is considering benefit cuts. In many states, benefits are guaranteed by the state constitution, so being paid benefits was assumed to be a certainty. But those promises no longer seem so credible.

The Detroit police and fireman pension estimates that it has more than $3 billion in assets, so it won’t run out of money any time soon. The concern is whether those assets are enough to pay the retirement benefits for future retirees like Dennis. To solve this problem, we need to understand exactly how underfunded these plans are and who will pay the short-fall. The sooner this is done, the solution will be cheaper and more certainty will be provided to state workers.

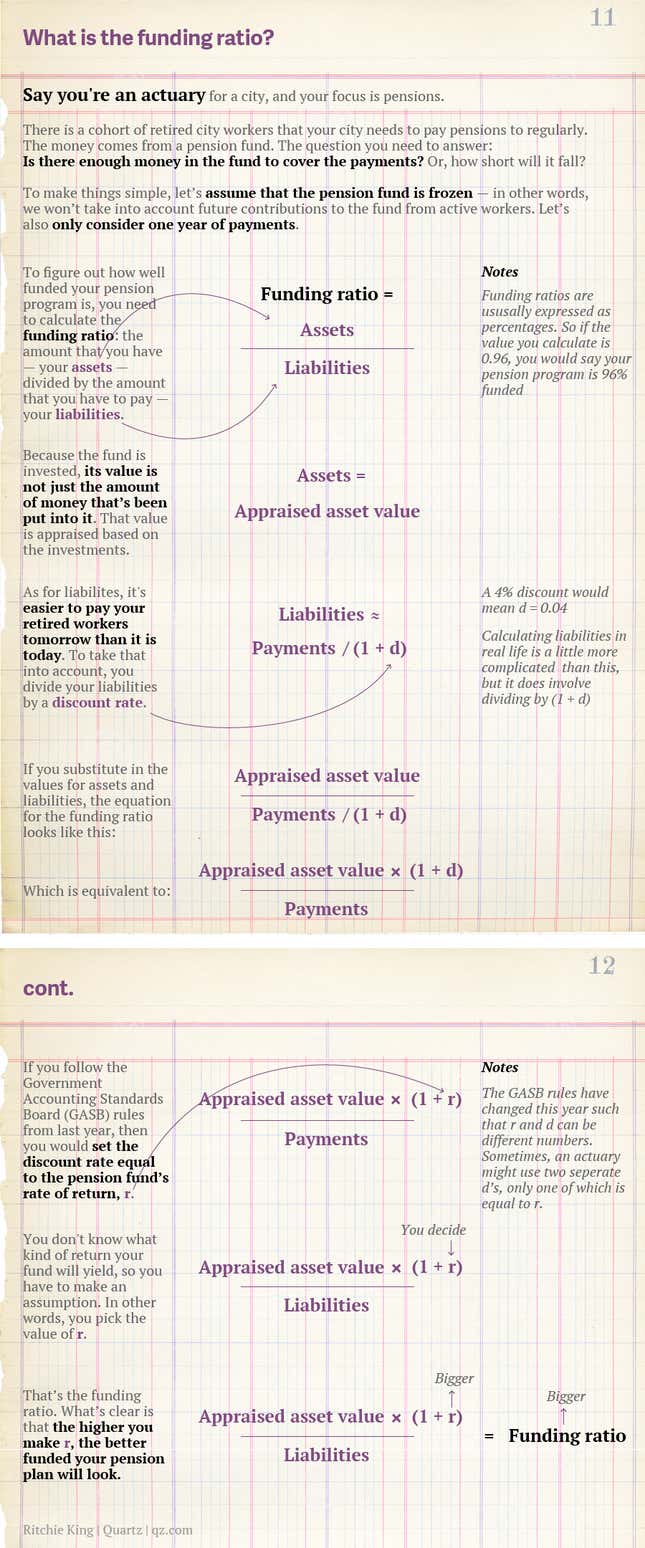

In Detroit, firefighters claim that their pension is 96% funded, meaning they reckon the current assets can finance 96% of the pension promises they’ve made to the police and fireman. Emergency manager Kevyn Orr says the plan is only 77% funded. The firefighters accuse Orr of using an unreliable estimate to cut their benefits. We can’t know what Orr’s motivations are, and I can’t vouch for the Millman report Orr is basing his funding rationale on, but he’s right—the pension is not nearly as well funded as it seems.

The value of a state pension is both the benefits paid to retirees, but the certainty that those benefits will be paid. When the workers retire they expect a fraction of their final salary, increasing with inflation, will be paid to them every year until they die. They will get that money no matter what happens to the stock market or how long they live. That kind of certainty is very valuable. It is why we pay for insurance, to ensure in all states of the world (even a house fire, sudden death of a loved one) you’ll have protection. The state governments have promised to pay out pensions no matter what happens. The problem is they don’t account for the cost of that guarantee.

The Detroit police and fireman retirement system assumed an 8% expected return for their assets and liabilities in 2011. An 8% return is very optimistic going forward. That assumes the 21st century will experience the same growth as the 20th century did. If the investment returns turn out to be lower, the pension fund will run out of money. The whole point is that is uncertain. Even if that 8% return is realized, on average, using it as the discount rate doesn’t account for the risk that in some years returns will be lower. Financial economists believe that the discount rate shouldn’t be the rate of return; it should be the price that reflects the costs of providing the benefits each year. That might be the treasury rate, if the benefits will always be paid, or maybe the municipal bond rate, what the states pay to borrow money. Some actuaries claim the expected return is fine for state pensions because you only need to earn 8% on average, some years you earn more others less. The problem with that is it’s much more expensive to raise capital, if you don’t have enough assets, when markets are down. Jeremy Gold’s research shows that using the expected return as a discount rate effectively shifts the cost of providing the guaranteed benefits to future generations, even when the average return is realized.

Cate Long reckons the right discount rate is a matter of opinion. But using a risk-appropriate discount rate is standard in finance and has been for decades, otherwise states are pretending the guarantee is free. If the fund doesn’t get an 8% return and Detroit can’t rely on its taxpayers, people like Dennis will be vulnerable to even larger benefit cuts in the future.

So who will pay for the guarantee? If we ignore the problem or pretend the current funding ratios are meaningful, it will be either future retirees, like Dennis, or future taxpayers (if there’s a bail-out in the future). If states or Federal governments bail-out the municipalities it will be current taxpayers. If the government issues debt to fund the pensions it will be future taxpayers. Ideally, everyone will share some of the burden. Once states and municipalities recognize the cost of the pensions they’ve promised, they’ll know if they can continue to provide them. In the private sector, once corporations were forced to account for their cost of their promises, they moved to private pension accounts, shifting the risk to their employees.

What can be done about this, a bailout or cutting benefits, is a critical question and has implications for other state pensions. But the sooner we can agree on the true funding rate and acknowledge the extent of the problem, the smaller the cost to people like Dennis will be.