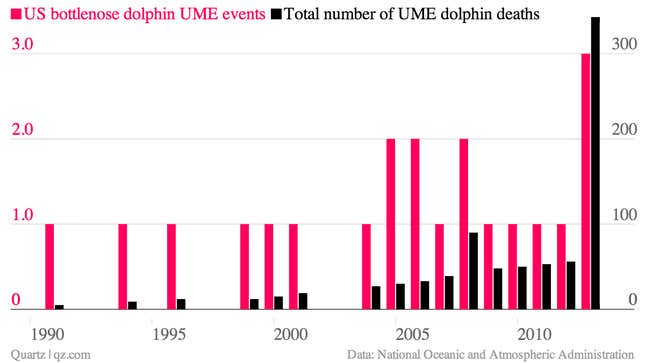

Since last month, scores of dolphins have washing up on Atlantic Ocean beaches, dying or already dead. Marine biologists are alarmed. Looking at the historical trend, you can see why:

The federal government has classified the situation as an “unusual mortality event” (UME), defined as a “a significant die-off of any marine mammal population” that “demands immediate response.”

Mass animal deaths happen a lot, it turns out. So far this year, we’ve had 600 manatees die in Florida and at least 362 sea lions in California. But despite fewer deaths so far, the bottlenose dolphin die-off is grabbing way more headlines. Perhaps it’s their mammalian familiarity—they name each other, have “the longest pure memory” of any animal (paywall), are self-aware, imitate humans, and the list goes on.

But there’s a better reason than empathy to care about mass dolphin-death: It may be telling us some scary things about the state of our seas.

“Dolphins are at the front lines of ocean health,” says Matt Huelsenbeck, a marine scientist at the non-profit Oceana. Dolphins are “the top predators—everything trickles [through them] … They’re more important than a lot of research buoys in terms of what’s going on.”

Factors that might cause bottlenose dolphins to croak in such high volumes include disease, toxin exposure, ocean acidification, and malnutrition. With this summer’s extraordinary death toll, disease tops the list of likely causes—specifically morbilivirus, a sea mammal version of the measles that killed between 740 and 1,200 bottlenose dolphins in the mid-Atlantic in 1987. So far, one dolphin has tested positive for the virus, which dolphins typically spread when they come up for air.

Even if it does turn out to be an epidemic, though, climate change and pollution likely play a role. Among similar species, diseases have been shown to spread more rapidly in higher water temperature. Plus, toxins like mercury weaken dolphins, making them more susceptible to pathogens by suppressing their immune systems.

But there are signs that the recent dolphin die-off is caused directly by pollution, not disease. Charles Potter, a marine mammal expert with the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, points to an unusually high number of males and calves that are turning up dead.

“Males don’t have a mechanism for shedding contaminants,” Potter told the Smithsonian Magazine’s blog. “The females shed significant amounts of their lipid-soluble contaminants through lactation, so the calf gets a hell of a dose early on in life, and some of the most outrageous levels of contaminants we’ve seen have been in calves.”

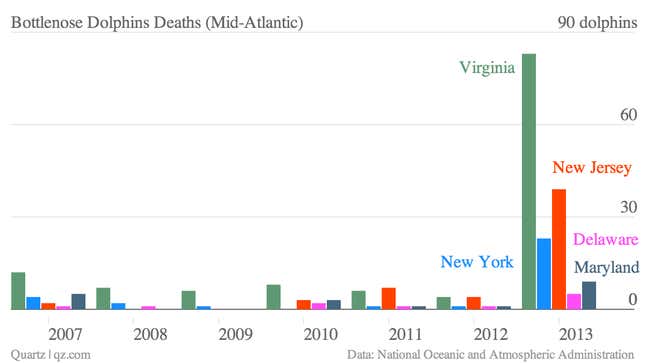

Regardless of the cause, the pace of death is picking up; in Virginia, 35 died in the last week alone, compared with 48 in July. Distressing numbers of dolphins are dying in Florida and Texas too, though those UMEs are thought to be unrelated. In fact, similar deaths occurred earlier this year in Italy and Australia and may be happening now in Norway. Though a couple of bottlenose UMEs happening every few years isn’t necessarily cause for worry, the rising incidence is certainly troubling: