The short answer: It will destroy their business model forever.

In the US, electrical utilities are in a charged battle—complete with negative political ads—against solar panel distributors over rules that both sides say could put them out of business. Consumers are caught in the middle.

A relatively new swathe of companies like Verengo, Sunrun, Sungevity and SolarCity have spent millions leasing solar equipment to homeowners and businesses. The cost of the lease is offset by savings on their electrical bill. Those savings come not just because of free power from the sun, but also through tax credits—and, most importantly today, because states allow those who have solar panels to sell any excess power back to the grid.

The more than 200,000 “distributed solar generators” in the US produce less than 1% of the country’s electricity. But that’s growing thanks to the falling cost of photovoltaics and financing from investors like Google. And this worries the big power companies, particularly two of the country’s largest, Pacific Gas & Electric and Southern California Edison.

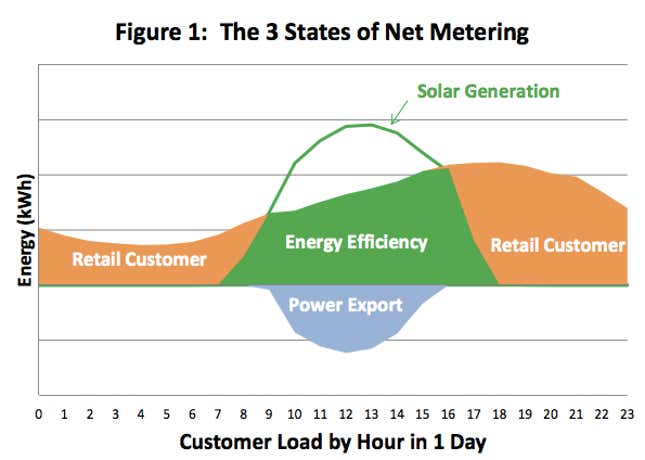

Utilities plan ahead for decades. Regulators approve the rates they can charge for electricity, based on the number of customers, the cost of generating power, and the cost of the infrastructure that it takes to get the power around. But when customers have a solar energy system, they take advantage of net electricity metering: However much energy the system returns to the grid—typically in the middle of the day—customers take off their electrical bills:

That means the grid is effectively paying the customers the retail price for their power. The grids aren’t happy about this because their retail rate includes not only the generation of the power but also all the fixed costs of the grid. The more solar customers there are treating the grid as a back-up, the more electrical companies say they’ll to raise rates on everybody else just to cover their capital expenses. One publicly commissioned study found the cost shifted onto non-solar users in California, where there are 170,000 homes and businesses with solar generators, is currently $0.38 a month.

And the more the utilities raise rates, the more it will make sense for customers to switch to distributed solar or use less energy, meaning less revenue for the power companies, meaning higher rates, and so on in a vicious cycle. Investors in power companies—especially the bond markets that fund their long-term capital projects—will demand more return, leading to higher rates, accelerating the “death spiral.”

Or at least that’s how the utilities paint the situation. They are demanding either new fees for anyone with a solar power system, or a cheaper, wholesale rate on the power they sell back to the grid. Regulators in California and Arizona, which have the two largest distributed solar customer bases, are considering doing just that in the next few months.

The solar companies, however, fear this will make solar more expensive, hurting both their business and the spread of green energy as direct subsidies fade away. They argue that the utilities are overplaying their hand. A study they commissioned argues that the utilities actually benefit from distributed solar’s ability to help the grid meet local demand. This is especially true, it says, when utilities are required to use a certain share of renewables, and when customers are paying “smart rates” that vary depending on when they purchase their power.

Utilities always want higher rates, this argument goes; solar proponents are fond of noting the $54 million rate-payers spend every month to cover the mothballed San Onofre nuclear plant for San Diego Gas & Electric, or the wide disparity in administrative costs for managing net metering. The largest utility, PG&E, charges nearly $30; its competitors charge $2-$3.

But even if the entire world one day ends up using solar panels, they’ll have to coexist with the conventional electrical grid for a very long time. So a regulatory solution has to be found. Which one isn’t clear yet, but both utilities and solar companies favor an analogy to the end of the old US telephone monopoly and the messy transition to today’s deregulated market in telecoms. The next year will be crucial in measuring that transition—and figuring out if you’ll ever have solar panels on your roof.