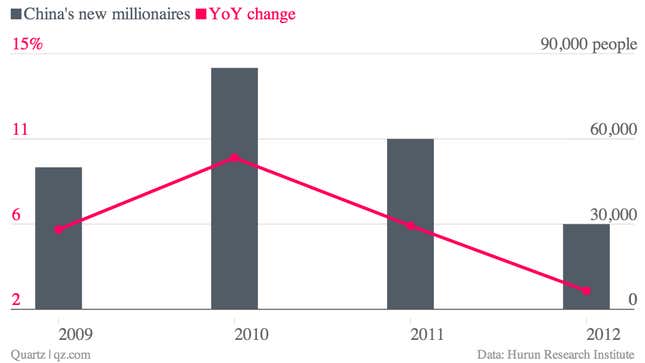

Last year, some 30,000 people entered entered China’s “millionaire” ranks, according to the latest Hurun Report (pdf), which defines that as those with more than $1.63 million in assets. The report competes with Forbes and Bloomberg to count the assets of China’s notorious “hidden rich,” who tend to obscure their wealth to avoid scrutiny of the government, media, and public. (Hurun’s findings are widely reported in the Chinese press.)

The starkest trend from 2012 is that the net growth of China’s millionaire ranks is slowing fast:

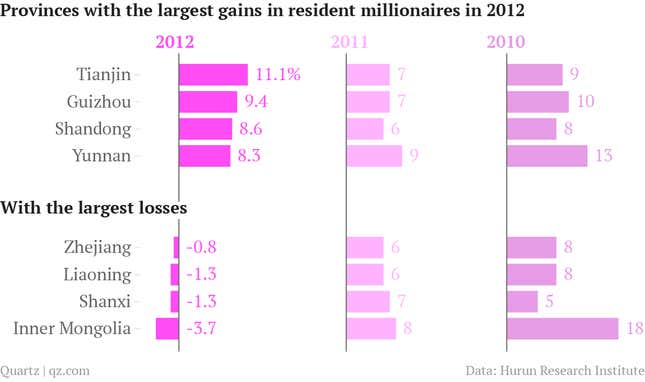

Underlying this is a striking break with past trends. In 2012, even as the tally in some areas surged, a slew of provinces actually shed millionaires. Zhejiang province, China’s entrepreneurial hotbed, had 1,000 fewer millionaires in 2012 than it did in 2011, while Inner Mongolia lost 500. Numbers in Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Hebei took a hit as well.

What happened to them?

The slowing economy likely reversed the fortunes of some former millionaires, particularly in industry-heavy provinces. Plummeting coal demand, which has exposed the sector’s excessive capacity and high debt, probably dented the wallets of some minor Shanxi and Inner Mongolia coal barons. (Inner Mongolia’s ghost city, Ordos, was funded by speculative coal money.) Similarly, falling steel demand and rampant overcapacity may have thinned the ranks of Hebei and Liaoning fat cats.

Another culprit could be real estate, the basis of many Chinese fortunes. A consistent 15% of millionaires earn their living from property speculation, according to Hurun. Even among non-real estate tycoons, the average value of property holdings in 2012 rose. And 64% of rich folks Hurun surveyed preferred investing in it, compared with 28% in 2008 (pdf, p.10).

But property prices fell in 2012, taking some fortunes with it. In Zhejiang, plunging housing prices set off a series of protests and left some developers without cash to cover debts.

Perhaps some of those developers didn’t make this year’s list. Then again, maybe they were part of Zhejiang’s spate of fleeing bosses (paywall). Many, though, were from the Zhejiang city of Wenzhou. In 2011, China’s slowdown collapsed Wenzhou’s bustling shadow finance system. As lenders began liquidating collateral—often residential property titles—the housing market crashed. Scores of Wenzhou businessmen fled the country.

Even those in Wenzhou without dangerous debts have been eyeing the exits. As a recent note on Wenzhou by Tracy Tian and David Cui of Bank of America/Merrill Lynch explained, those with means have bought real estate abroad, often baking “their overseas property investment choice into their decision-making for immigration.”

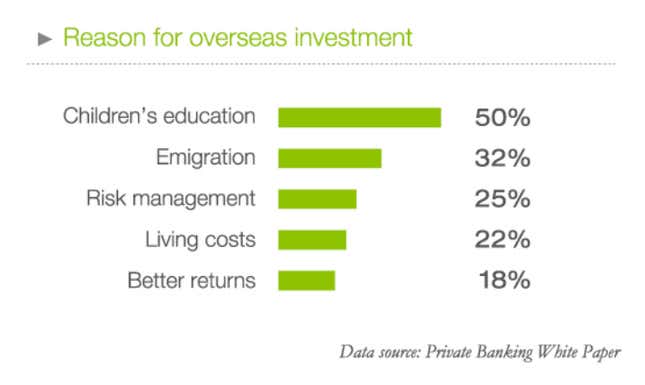

Last year’s Hurun report picked up on that, too. Hailing “the rise of emigration out of China” (pdf, p. 2), it reported that that “60% of millionaires are applying or considering emigrating overseas,” with many buying property overseas as a way of “facilitating emigration.”