Biking? Google probably knows you are. Up a mountain? It probably knows that, too.

The Alphabet subsidiary’s location-hungry tentacles are quietly lurking behind some of the most innovative features of its Android mobile operating system. Once those tentacles latch on, phones using Android begin silently transmitting data back to the servers of Google, including everything from GPS coordinates to nearby wifi networks, barometric pressure, and even a guess at the phone-holder’s current activity. Although the product behind those transmissions is opt-in, for Android users it can be hard to avoid and even harder to understand. Opting in is also required to use several of Android’s marquee features.

As a result, Google holds more extensive data on Android users than some ever realize. That data can be used by the company to sell targeted advertising. It can also be used to track into stores those consumers who saw ads on their phone or computer urging them to visit.1 This also means governments and courts can request the detailed data on an individual’s whereabouts.

While you’ve probably never heard of it, “Location History” is a longtime Google product with origins in the now-defunct Google Latitude. (Launched in 2009, that app allowed users to constantly broadcast their location to friends.) Today, Location History is used to power features like traffic predictions and restaurant recommendations. While it is not enabled on an Android phone by default—or even suggested to be turned on when setting up a new phone—activating Location History is subtly baked into setup for apps like Google Maps, Photos, the Google Assistant, and the primary Google app. In testing multiple phones, Quartz found that none of those apps use the same language to describe what happens when Location History is enabled, and none explicitly indicate that activation will allow every Google app, not just the one seeking permission, to access Location History data.

Quartz was able to capture transmissions of Location History information on three phones from different manufacturers, running various recent versions of Android. To accomplish this, we created a portable internet-connected wifi network that could eavesdrop and forward all of the transmissions that the devices connected to it broadcast and received.2 None of the devices had SIM cards inserted. We walked around urban areas; shopping centers; and into stores, restaurants, and bars. The rig recorded every relevant network request3 made by the Google Pixel 2, Samsung Galaxy S8, and Moto Z Droid that we were carrying.

According to our analysis of the phones’ transmissions, this is just some of the information that gets periodically sent to Google’s servers when Location History is enabled:

- A list of types of movements that your phone thinks you could be doing, by likelihood. (e.g. walking: 51%, onBicycle: 4%, inRailVehicle: 3%)

- The barometric pressure

- Whether or not you’re connected to wifi

- The MAC address—which is a unique identifier—of the wifi access point you’re connected to

- The MAC address, signal strength, and frequency of every nearby wifi access point

- The MAC address, identifier, type, and two measures of signal strength of every nearby Bluetooth beacon

- The charge level of your phone battery and whether or not your phone is charging

- The voltage of your battery

- The GPS coordinates of your phone and the accuracy of those coordinates

- The GPS elevation and the accuracy of that

“That goes beyond what you’d expect for Location History,” Bill Budington a security engineer for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told Quartz when these transmissions were described to him, “especially in terms of predicted activity.” The EFF is a nonprofit organization that advocates for digital civil liberties, freedom, and privacy, which both I and Google have made charitable contributions to in the past.4

Google, accurately, describes Location History as entirely opt-in. ”With your permission, Google uses your Location History to deliver better results and recommendations on Google products,” a spokesman wrote to Quartz in an email. “For example, you can receive traffic predictions for your daily commute, view photos grouped by locations, see recommendations based on places you’ve visited, and even locate a missing phone. Location History is entirely opt-in, and you can always edit, delete, or turn it off at any time.”

When asked to opt in, however, the full implications of enabling Location History are rarely made clear. Here are some of the ways Google apps ask users to enable Location History.

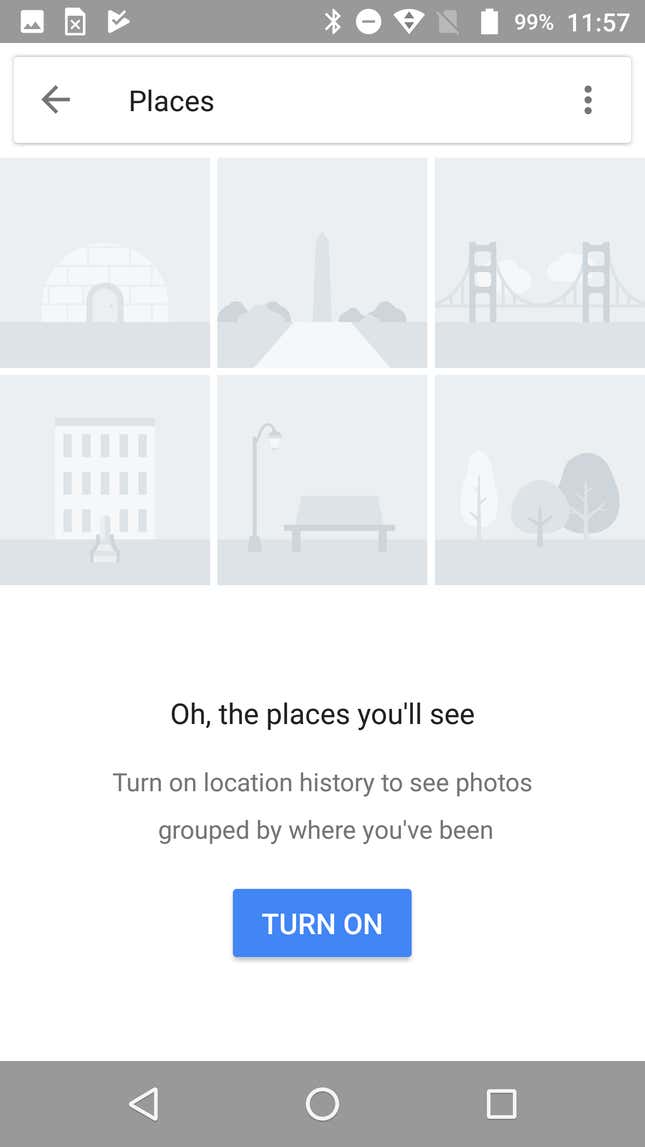

Google Photos

When the “Places” album is selected, the app requests to turn on Location History. The prompt says that Location History will allow you to “see photos grouped by where you’ve been.” It doesn’t say anything about Google using that information for other purposes. It doesn’t mention that in exchange for organizing your photos, you let Google record what stores you’re shopping in and what restaurants you’re eating at by collecting information about nearby Bluetooth beacons and wifi networks. There is no option to limit Location History to only be used for sorting photos.

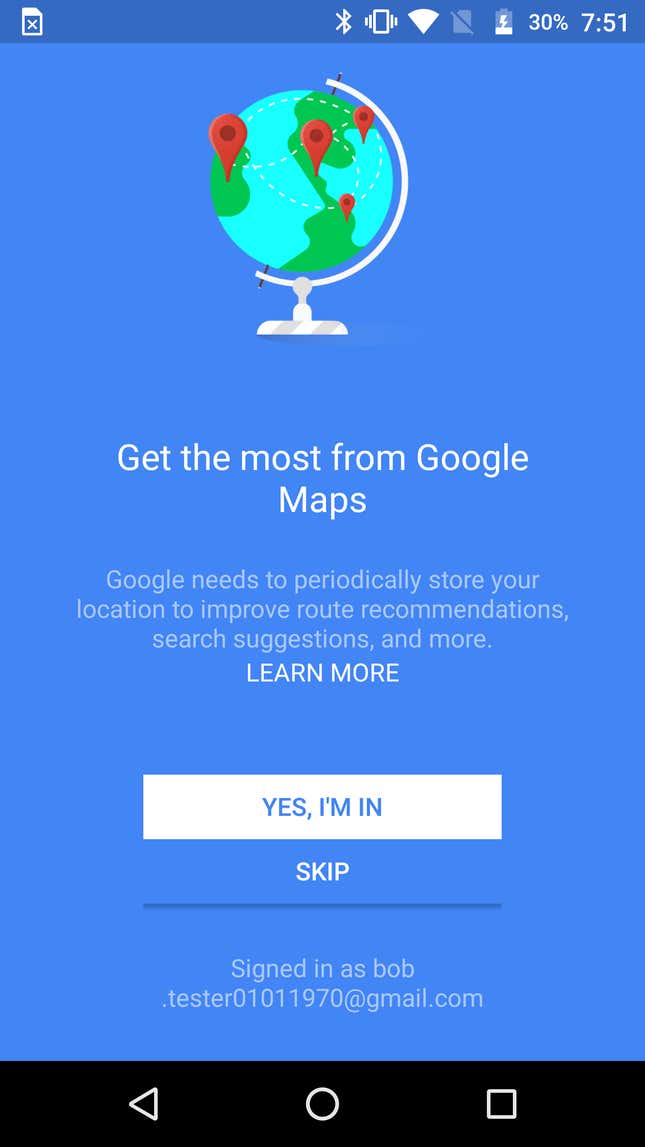

Google Maps

In Google Maps, users are encouraged to “Get the most from Google Maps” by turning on Location History. “Google needs to periodically store your location to improve route recommendations, search suggestions and more,” the full-screen prompt explains. Those suggestions come in exchange for Google knowing how often you go for a run and how often you charge your battery.

Google App

In the primary Google App, the prompt to turn on Location History occurred almost immediately on one of the Phones we tested. On another, it only appeared when trying to activate information about local road traffic. Tapping “Learn More” reveals that Google plans to use this information not just for aiding a commute, but also to give you “more useful ads on and off Google.”

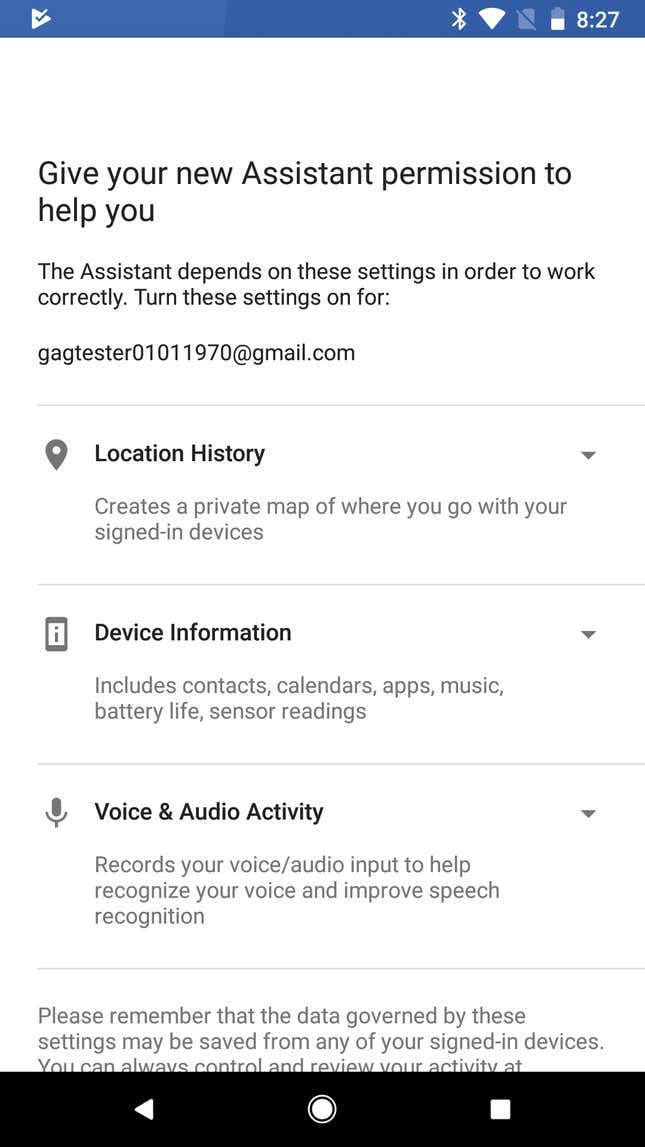

Google Assistant

On first use, the Google Assistant’s activation screen immediately makes Location History look like a requirement. “The Assistant depends on these settings in order to work,” the screen says, describing Location History as creating a “private map of where you go with your signed-in devices.”5 It makes no mention of sharing your wifi connection, only that it will “regularly obtain location data from this device, including when you aren’t using a specific Google product.” Allowing these permissions is required to activate Google Assistant, although if Location History is disabled after Google Assistant is set up, the assistant will still function and does not seem to prompt for it to be re-enabled.

Google Assistant is of strategic importance to the company’s efforts to keep users in its ecosystem of devices, apps, and services rather than those of Apple, Amazon, or Microsoft. Most recently, all of these companies have been focused on in-home appliances that respond to voice and can assist with various routine tasks like playing music, calling a taxi, or ordering laundry detergent.

Your Location History

Android users can check some of the information Google has collected about them by looking at “Your timeline” in Google Maps. (Google’s information page on how to access it can be found here.) These instructions show how to turn off Location History entirely.