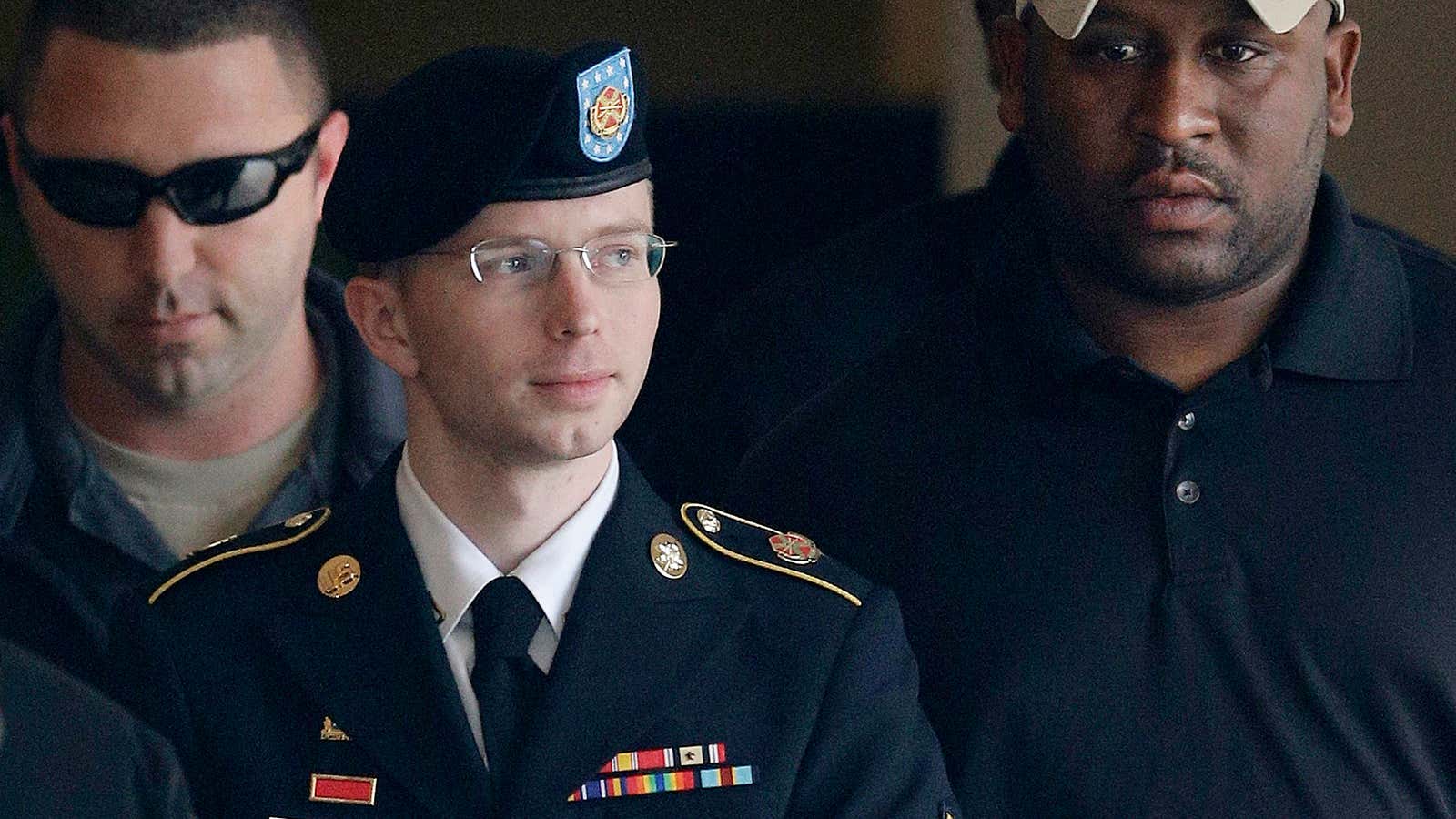

The media tied themselves into knots on Thursday (Aug. 22) when the person they had known until then as Bradley Manning, sentenced a day earlier to 35 years for leaking government secrets to Wikileaks, announced that she was a woman named Chelsea. Reporting this, some newspapers ended up where you least expected them to be: the oh-so-liberal New York Times stuck doggedly to “Bradley” and male pronouns, while Britain’s conservative gossip rag the Daily Mail called her “Chelsea” and “she/her” throughout. One article from Reuters went to extraordinary lengths, writing “Manning” more than a dozen times and even breaking rules of grammar just to avoid using any pronouns at all.

Now, to be fair to the media, the organizations whose job it is to explain transgender issues to the public weren’t much help. Reporters who turned, as I did, to the websites of groups like GLAAD, TransEquality, the Human Rights Campaign, or the UK’s Trans Media Watch when the news about Manning broke would have found admonitions to use the pronouns a transgendered person asks you to use—but no advice on how to write about the very moment at which those pronouns changed, or about the person’s life before then. Should Manning be “Bradley” when writing about her (his?) tour of duty in Iraq? If not, why not?

In fact the answer is simple—”Chelsea”, always—and so is the reasoning, once you know it. To come out as transgender is to acknowledge the gender you have always had, regardless of what your body seemed to be. The gender you used to go by is something you never really were. In that light, for someone else to then keep on using it just looks like stubbornness, or malice.

So what are the media to do? “‘We can’t just spring a new name and a new pronoun’ on readers with no explanation,” a Times editor complained, when the paper’s public editor asked why it had stuck with “Bradley”. Well, indeed you can’t. But you can with explanation, and the explanation part really isn’t that hard.

At Quartz, where we have the privilege to still be making up the style book as we go along, I added a new entry yesterday, under “pronouns”:

If you know them, respect a person’s preferences. But in general, remember that being transgender doesn’t mean you’ve changed your gender. It means recognizing the gender you’ve always had, and that the body you were born with doesn’t match it.

So don’t refer to a trans person’s “new” gender but her “real” gender. And use the name and pronouns she uses now, even when writing about her life before she came out as trans.

If this gets weird, e.g. “Lucy and her wife were married in a Catholic church,” you can add an explanation, like “when Lucy was still known as Bob” or “when Lucy was outwardly male.” But don’t write things like “Before Bob became Lucy, he and his wife were married in a Catholic church.”

In the complaint of the Times editor, you can almost hear the objections piling up. “Are we going to have to do this for everybody who wants it?” “What if ‘she’ changes her mind again?” ”Are people going to start demanding to be called ‘ze’ or ‘ey’ instead?”

The answer is: Yes, all that’s going to happen, and you’d better get used to it. More people will come out as trans, and need their pronouns changed. A few will indeed decide it was a mistake and want them changed back. And more and more people will find it normal not only to switch between “he” and “she”, but to treat gender as what one young student calls an “amorphous blob”. A couple of years ago I wrote about Justin Bond, a New York cabaret artist who has adopted the pronoun “v” and a gender called simply “trans.” In an otherwise glowing profile, New York magazine referred to Bond as “he/him.” After v (see? Not that hard) complained, the contrite magazine changed all the references.

And this is just the beginning. Decades from now, people may be choosing surgery to give them characteristics of both sexes. Perhaps people born male will be able to have uteruses and carry babies to term. Perhaps, as in some science-fiction novels, we’ll have a whole range of genders.

In other words, the linguistic conundrums of transgenderism aren’t going to go away. Better to embrace them, and accept the fact that they’re only going to get more interesting.