What does discovering a great big gob of oil do for a company’s share price? Seems it’s a matter of perception. If the company says it has discovered a “giant” new oilfield, its shares are likely to rise almost twice as much as if it calls the find “major,” and three times as much as if it uses the word “significant,” according to a new study.

The impact of the different shades of oilfield braggadocio on share price was studied by Oswald Clint and Rob West, two analysts for Sanford Bernstein, the equity research firm. In a note to clients yesterday, the pair said they collated 10,000 pieces of energy news and company press releases over the last five years.

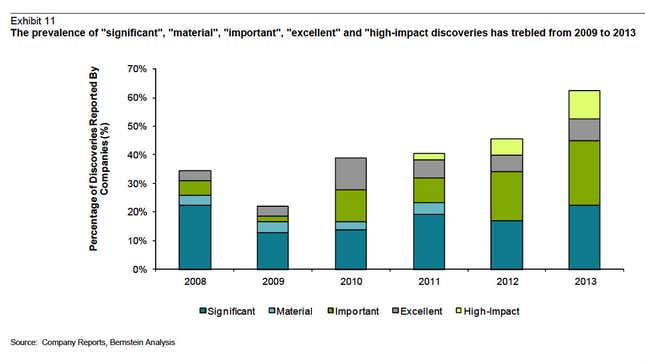

One big takeaway is that in 2009, major oil companies were a relatively modest lot. When they discovered a new oilfield, there was an 80% likelihood that they would simply go about their business and say very little about it. The other 20% of the time, they used embroideries such as “important,” “excellent,” “high impact” or “significant” to describe their oilfield success.

But just four years later, they are much more boastful. If they find oil, there is a 60% chance they will use such language. Clint and West call it oilfield “inflation.” Here are the results year by year.

The difference has more to do with pressure to satisfy investors than a run of good luck or great skill on the oil patch, they said. When they indexed market reaction to these terms, they found a company’s share price rose by 0.4% for a “significant” discovery, 0.6% for a “major” discovery and fully 1.1% for a “giant” find.

“Are we paying double today for high-impact exploration or high impact press releases?” the Bernstein analysts ask. They come down firmly on the latter.

Looking at European oil majors, Bernstein found little correlation between the more extravagant language and better drilling results. Their average drilling success for 2010-2012 was 1-for-1 (one barrel found for every barrel produced), slightly worse than the 1.1 barrel found for each produced in 2007-2009.

One reason for the language inflation may be that the costs of finding and drilling for oil are rising, Bernstein says, which puts more pressure on companies to impress their investors. Exploration spending has gone up by 13.5% a year at a compound annual rate over the last five years. “With higher spending on exploration… it is not surprising that today we are hearing news of ‘extraordinary results’ from appraisal wells and other language that aims to maximize impact,” the firm said.