When the United States was choosing a location in Indonesia for its first @America cultural center—a new, interactive, social-media focused face of diplomacy—it decided to stay far away from the embassies of the city center. A stand-alone building would be too inconspicuous in dense, traffic-clogged Jakarta. What it needed was a space near heavy foot-traffic, ready parking, and good name recognition.

The final choice? The third floor of the vast, air-conditioned, luxurious, Pacific Place Mall in south Jakarta.

East Asia’s gigantic developing megalopolises—Beijing, Shanghai, Jakarta, Manila, Bangkok, and Saigon—are building vast new urban landscapes centered on what was once the purview of suburban America: the indoor, privately-owned shopping mall, the sizes of which are beyond anything in the global north.

In modern economics, a developing country’s middle class is defined by its ability to consume at levels at or near those of the US, Japan, or Europe. Asia’s new malls are bubbles of modernity, built on vast scales as symbols of this growing class. They are meeting spaces, glossy, air-conditioned indoor parks, where you can ignore the air pollution, poverty, and heat of the real world.

A brief history

In 1992, the year Bill Clinton was elected president, the largest mall in the world, the Mall of America, opened outside of Minneapolis, Minnesota. It was a behemoth that quickly became one of the top tourist destinations in the country and also a symbol of American consumer excess. On the outside, it was just a large, ugly square surrounded by football fields of parking lots, but that was not the point. What mattered was what was inside: over 200 shops, an amusement park, 14 screens of cinemas, and a giant food court with every single American fast-food option. The richest country in the world had built a symbol for its own version of modernity.

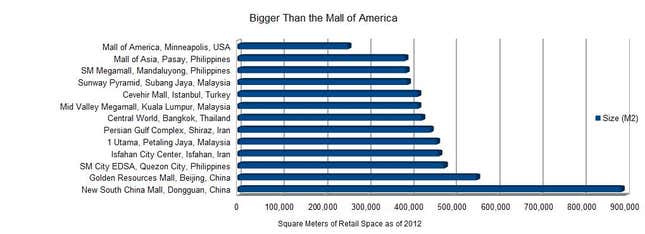

It was also in the early ’90s that China’s massive economic expansion began, joining the Asian Tigers of Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia and Taiwan to form the world’s second engine of growth. However, it wasn’t until the onset of the new millennium, after the 1997 financial crisis that Asia really took off with Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines rapidly developing. Then, the malls became bigger and bigger. Today, there are 18 malls in Asia (and one in Canada) larger than the Mall of America, with several more under construction.

The new public space

It is not only the size but also the sheer number of malls that is mind-boggling. The boom has transformed Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, into the proud owner of over 170 shopping malls, the most in the world.

These malls have been built on what were once parks. As recently as 1983, the city still had 35% of its land in open, green areas. Today, according to Green Map Jakarta, that number has dropped to an astounding 6%, one of the lowest in the world.

When Jakartans go for a walk, they have few options beside the malls. Sidewalks are non-existent, overtaken by motorcycles or vendors, the parks are gone, and getting in and out of the city to the countryside a nightmare. As the urban heat effect and lack of trees make Jakarta both hotter and drier, the malls become a refuge of air-conditioning (from reliable, generator-sourced electricity) for a population increasingly more accustomed to living in a climate-controlled world.

As money flows into real estate from foreign investors and revenue from Indonesia’s rich natural resources, the construction boom continues. Cheap money is turned into malls, often built right beside each other. There’s the question whether such high demand even exists. Grand Indonesia, a vast complex build not far from Monas, Indonesia’s towering national monument, offered free rent for a time to many of its tenants in order to keep them from moving elsewhere.

That means that today in Jakarta, the poor can actually pay more for housing (on average $20-$60 per square meter) than multinational chains like Gucci, Prada, or Gap pay for retail space, which can be $50 a month per square meter at the few top malls and nearly nothing at less popular ones.

In China, home to the world’s largest (and mostly empty) mall, the boom is leading to such a high vacancy rate that many malls have not only been waiving rent, but actually paying retailers like H&M and Zara to move in.

There are speculations that China’s mall boom has been funded by easy credit, lax central oversight, and corruption. Despite high vacancy rates and numerous “ghost malls,” China still has more new malls in development than any other country in the world, by a wide margin. This is the real estate bubble that may be the cause of China’s recent slowdown. Profit margins are thin, despite China’s growing middle class, though international brands are cashing in on the newly rich’s love of high-end goods. China is soon expected to overtake Japan and the United States as the world’s top luxury market.

The city of malls

But it is Singapore, Asia’s crowning economic jewel, which has the world’s shopping mecca—Orchard Road, a street where 22 malls are lined up one against another for over a mile. The street is in a perpetual state of flux, as malls constantly remodel, rebuild, and renovate in order attract customers. Most are owned by conglomerates like CapitaMalls Asia, which operates over 100 malls in Asia. The vast crowds on the street are a mix of locals, but mostly, tourists from Europe, China, and neighboring countries, attracted by Singapore’s status as a trade hub, its low sales tax, and access to the widest variety of luxury goods in Asia.

That’s how vacancy rates stay low, and the malls, amazingly, stay profitable.

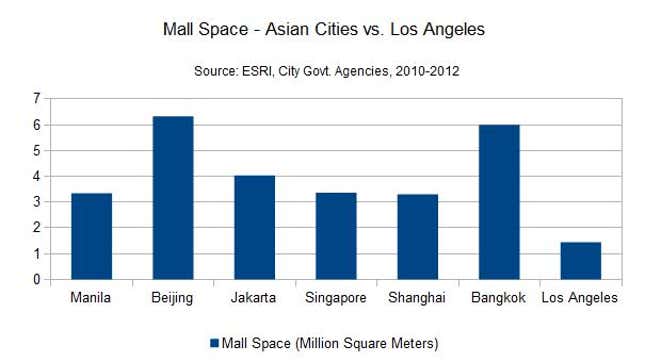

Singapore, however, is a small country in a strategic location alongside the world’s busiest shipping route, the Straits of Malacca. It is also a regional hub for trade and investment, and its malls, not to mention vast land reclamation projects and glistening new skyscrapers, are funded by foreign investors who see the country as a safe investment. While this model might work here, it is ill-fitted for larger, more economically diverse countries like China and Indonesia. Hence, empty mega-malls in Dongguan, and bare-bones rents in Jakarta. No matter how fast China’s middle class grows, it cannot sustain a city like Chengdu having four times as many malls as similarly sized Los Angeles. Despite government attempts to spur consumer spending, retail sales are already slowing. Foreign luxury brands are making money, but margins are thin, or negative, at stores targeting middle and lower-class Chinese.

All this evidence points to the fact that peak-mall in Asia may be closer than people think. In Jakarta, despite the crowds that pack Pacific Place and its now popular @America center every weekend, the young, consumer-savvy urban population is seeking something different. In one of this first decisions after being elected, the new, young, and incredibly popular Mayor of Jakarta, Joko Widodo, whose no-nonsense attitude and unwavering dedication to fighting corruption have many calling him “Indonesia’s Obama,” put in place a moratorium on new shopping malls, a decision received with popular support.

The reality that malls and consumerism only cater to a small percentage of the population is becoming more and more apparent. Remember—Asia’s economic growth was built on manufacturing and natural resources. It’s the transition to an American-style consumer economy that is faltering, perhaps because that mode—built in an era of cheap oil and plentiful space—is untenable in today’s world. What is now needed is sustainable consumption, one in which assets are spent not on giant shopping malls, but health, the environment, and transportation. China, Indonesia the Philippines, and China might be leading the world in malls, but they rank a paltry 101st, 114th, and 121st, respectively, in the United Nations Human Development Index country rankings.

Here, shopping malls are not symbols of a developed economy, but of misplaced priorities and inefficiencies, surface monuments trying to hide the darker reality.

In the coming years, expect Asia’s economic reality to come in balance. Until then, we’ll see how many more giant, empty malls it will take before development priorities finally change.