Facebook just reached the 1 billion user milestone, but the company has a problem: The more users it has, the less money it will make on each one, because its next cohort of users from the developing world aren’t nearly as wealthy as the existing users. So it will be difficult, if not impossible, for the company to significantly increase its revenue through growth in its user base alone. Recent trends in the company’s average revenue per user, or ARPU, and public statements by CEO and founder Mark Zuckerberg both support this conclusion.

1. Facebook’s move into emerging markets is an average revenue per user (ARPU) trap

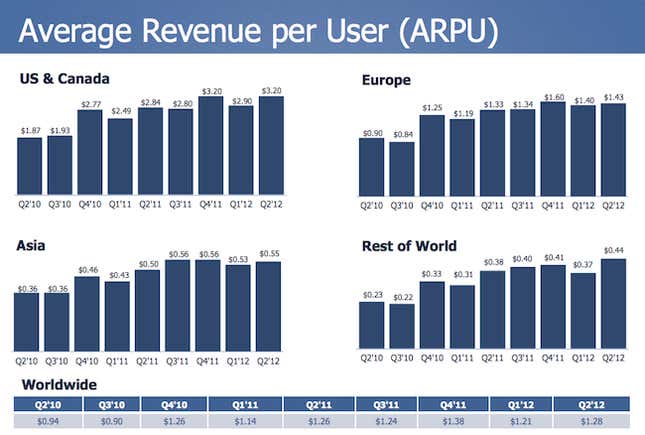

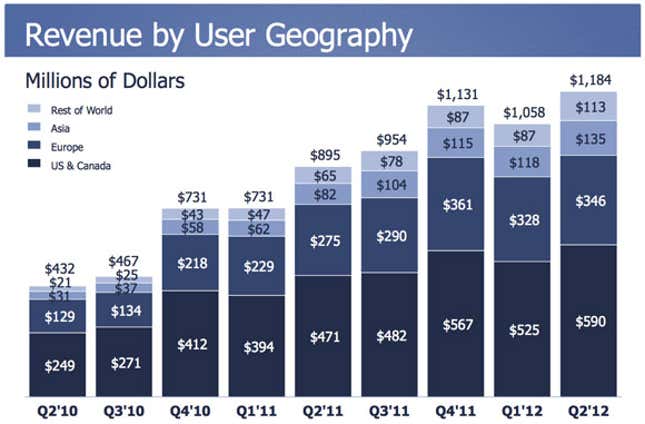

As of the company’s most recent quarterly results, Facebook is making on average only $1.28 per customer, which is a hair above the company’s revenue per user in the first quarter of this year but below the $1.38 average ARPU for all of 2011. (For comparison, Google’s revenue per user is $7.14.) If Facebook’s revenue per user had just held steady, the company would have an extra $100 million in revenue per quarter.

Why is Facebook’s revenue per user going down? It’s simple: All of the company’s expansion is in the developing world, where people simply have less money. As I explained in my deep dive on how Facebook got to a billion users in the first place (and how it will reach the next billion) almost all of that growth is coming through Facebook’s various efforts to get in front of users in the developing world by convincing their mobile carriers to make Facebook free, an effort called Facebook Zero.

Facebook’s revenue per user differs significantly between rich and developing countries, which means that the more users Facebook grabs from “the next billion,” the lower its revenue per user will sink.

In addition, Facebook CEO and founder Mark Zuckerberg just told Businessweek that 600 million Facebook users reach the site through mobile phone, and in the developing world, that is practically the only way they are reaching the site. Facebook is, by its own account, even worse at monetizing mobile users than users coming through PCs.

2. Facebook’s fortunes are now tied to those of the global middle class

The primary reason that mobile carriers in emerging markets agreed to make Facebook free on their networks, forcing them to eat the associated data costs, is that Facebook has apparently helped these carriers to get more users consuming data on non-Facebook sites. This data is charged at the normal rate, helping these carriers to raise their own flagging average revenue per user figures. But now Facebook’s fate is the same as the carriers that are giving it away for free: having addressed the demand for connectivity among the middle and upper classes, new customers coming onto mobile services tend to be those who are progressively less wealthy.

To the extent that the users who are accessing Facebook through three year old, text-only gray-market Nokia handsets will graduate to the middle class, Facebook’s strategy of capturing them now is a good one. For many of these users, Facebook is the web, being the first experience they ever have with the internet. The problem is that it may take years, even decades for these consumers to graduate to levels of per-capita GDP comparable to the middle class in wealthier countries. Are Facebook’s shareholders willing to wait that long? Can the company even hold onto its users for that long before being supplanted by the next big thing in social networking?

3. So can Facebook justify its stock price?

If Facebook can boost its average revenue per user, the company has a chance to meet the high expectations set by its initial public offering, when the stock was at $38. (As of this writing, the stock is trading at around $22 a share.) And Facebook is certainly trying: the company is testing a new mobile ad network that should allow the company to advertise to you on apps outside of Facebook.

But the market is having a hard time determining the future of Facebook as analysts’ expectations are all over the place. There is a strong case to be made that in order for the company to reach its IPO level of valuation on fundamentals, it would have to increase its revenue seven-fold.

Perhaps one reason that the outlook on Facebook is so mixed is that analysts recognize–and Mark Zuckerberg keeps saying–that in the short term, the company is going to have problems generating the kind of revenue that investors would like to see. Long term, a bet on Facebook is a bet on the idea that the company can figure out how to substantially increase its revenue per user in the developing world, and that all of Facebook’s next billion users will increase their incomes quickly enough to justify similar levels of ad spending.