The last five years have brought about catastrophic weather, sweeping political unrest in the Middle East and Northern Africa, and a global financial crisis of historic proportions. And yet, on the whole, the world has emerged happier than it was before, according to the UN World Happiness report released on Monday.

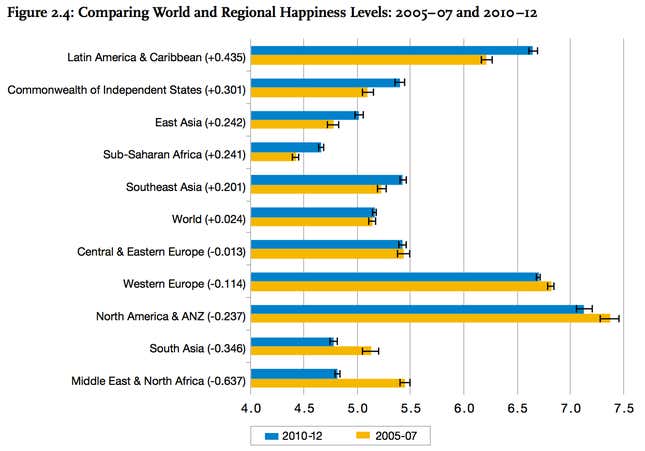

The report, which measured happiness across the world using six subcategories—GDP per capita, life expectancy, social support, perceptions of corruption, prevalence of generosity, and freedom to make life choices—found that increases in global happiness were largely driven by changes in specific regions—most specifically Latin America and the Caribbean, East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Conversely, dwindling results in Western Europe, North America, South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa dragged on the global uptick.

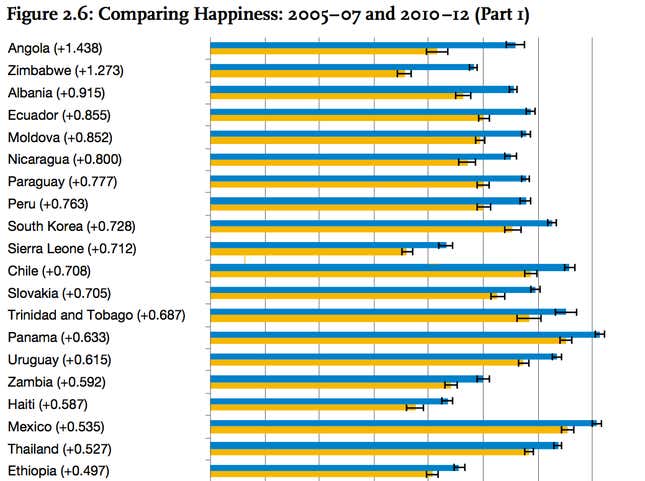

Improvements in the quality of life have been most pronounced in Latin America and the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa, where the vast majority of countries included in the survey reported significant increases in happiness—a handful of which registered the largest increases from 2007 to 2012 (see below). The spike is largely due to sharp decreases in perceptions of corruption and increases in life-choice freedoms.

On the opposite side of the spectrum sit the Middle East and Northern Africa, where political unrest has unraveled much of the region, and North America and Western Europe, the regions hit hardest by the financial crisis. Despite modest increases in GDP per capita, the regions suffered significant decreases in happiness, largely caused by substantial dips in perceived social support and life-choice freedoms. Egypt, the recent epicenter of North African political unrest, suffered the largest drop in happiness from 2007 to 2012 amongst all countries.

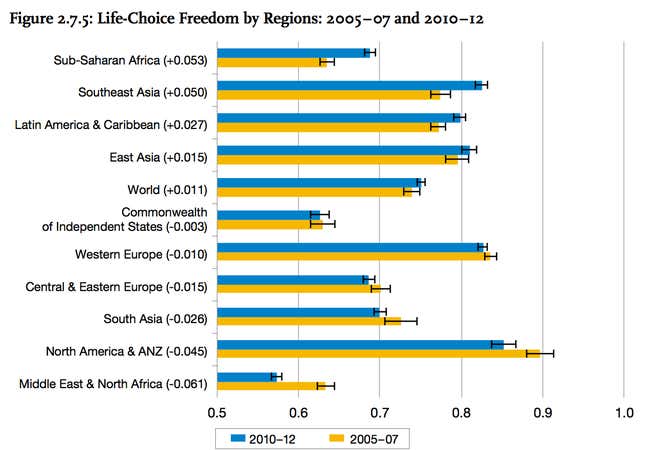

On the surface, the bulk of the findings, especially those associated with drops in happiness, are more or less common sense; Political strife and violence and financial crises have understandably taken their toll on certain regions. But drilling down more specifically, overall happiness is most in line with a peoples’ freedom to make life choices. Events like civil war and financial crises have impinged on people’s freedoms and, by extension, limited their happiness.

In all regions save for the Commonwealth of Independent States, a boost in perceived freedoms accompanied a boost in happiness, and, conversely, decreases in perceived freedoms were paired with in decreases in happiness. Money, social support, corruption, and the other factors may not be as related to happiness as freedom. Last December, Economist Miles Kimball noted a similar trend. For his National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper “Beyond Happiness and Life Satisfaction: Toward Well-Being Indices Based on Stated Preference,” he asked 4,600 US adults to “identify both what people wanted for themselves and what they wanted for the nation as a whole.” Kimball found that freedom came first.

Of course, just because perceived freedom coincided most closely with happiness doesn’t mean the relationship is causal. But more and more countries seem to be making that jump; many have started looking to happiness metrics as one way to measure government success. Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index, for instance, includes 124 components—some of which are economic, but many of which are not. Brazil, New Zealand and the UK, among others, are hopping on the happiness bandwagon.