Hartmut Esslinger knows a thing or two about industrial design and what it’s done for Apple. He worked directly with Steve Jobs to establish a “design language” that was used on the Macintosh line of computers for over a decade. Esslinger’s iconoclastic firm had already designed over 100 products for Sony when he signed an exclusive, $1-million-a-year contract with Apple in 1982.

But that Apple is mostly gone, says Esslinger in an interview with Quartz. The Apple of today resembles Sony of the 1980’s, says Esslinger, who witnessed the succession process at Sony first-hand: The visionary founder has been replaced by leaders who aren’t thinking beyond refinement and increasing profit.

Update: Harmut writes to clarify his comments to Quartz. He says that “the Apple of today still has great design at its core, but must maintain [its] passion for cutting edge innovation. […] Apple is still leading but must speed up its innovation again.”

“Steve Jobs was a man who didn’t care for any rational argument why something should not be tried,” says Esslinger. “He said a lot of ‘no,’ but he also said a lot of ‘yes’ to things and he stubbornly insisted on trying new things.”

One reason Esslinger is willing to recount his time with Jobs is that on October 9, at the Frankfurt book fair, he will release a design and management memoir recounting his time with Jobs, called Keep it Simple. (Here’s an excerpt from the book, complete with original design drawings from the early days of Apple.)

The origins of a design-led culture at Apple

By Esslinger’s own account, when he started working with Jobs in 1982, Apple was a fractious company in which designers reported to engineers and many in Apple’s corporate structure were openly hostile to the founder’s influence. (By 1985, Jobs had been forced out; he returned in 1996.) At the start of his work with Esslinger, Jobs knew that design could help define Apple’s brand in a way that no amount of marketing could accomplish, and from the introduction of the Macintosh SE, Esslinger’s “Snow White” design language defined the appearance of the Macintosh, visually integrating its outer plastic shell with the software it contained.

As early as 1983, Jobs had already conceived of a “book-like computer,” though the project was not discussed outside the company. That vision eventually led to the Apple Newton, a tablet that failed, and the iPhone and iPad, which made history. That kind of vision is now lacking at Apple, Esslinger says.

“As soon as you can copy something [like the iPhone,] it’s not smart enough anymore,” he says. “I think Apple has reached in a certain way a saturation—the curve [of innovation] was really steep seven to eight years ago […] but now my iPhone is so full I am deleting apps because I want to keep it simple.”

What the next Apple might come up with

So if a disruptive new company—the Apple of today—were to emerge, what kinds of products might it make? Esslinger, who retired from Frog design, the company he founded, in 2006, now teaches all over the world and especially in China, and he says that his students are primarily focused on three-dimensional interfaces as the “next big thing.” Their inspiration? Video games.

“Our students in China and in Germany, they come from the video game culture, and the video games are 3D,” says Esslinger. “I did a workshop a couple of years ago in Switzerland, and even MBAs said enterprise software should be like a video game.”

Just as important to the future of human-computer interaction, says Esslinger, will be a re-thinking of the integration of hardware and software. One example he gave was concept designs Frog did in collaboration with MIT, for flexible computers that responded to squeezing and other types of unconventional touch input.

“I think flat screens have reached a level of saturation,” says Esslinger. “Screens don’t have to be all right angles—the cheapest way is not always the best way. […] Not every country on earth likes square shapes, The cache and the memory makes it easier to have a rectangular screen, but it doesn’t have to be like that. There is much more freedom than we think we have.” (1)

Asia, young upstarts in the wings

Some of that radical thinking could come out of China, where Esslinger currently teaches. “What’s happening in China right now is a paradigm shift where they realize they have to innovate, and can’t just make cheap products,” says Esslinger. “The first generation of entrepreneurs just wanted to make money, but now you have a guy like Richard Yu, CEO of Huawei, announcing in public, ‘I want to beat Apple and Samsung.'”

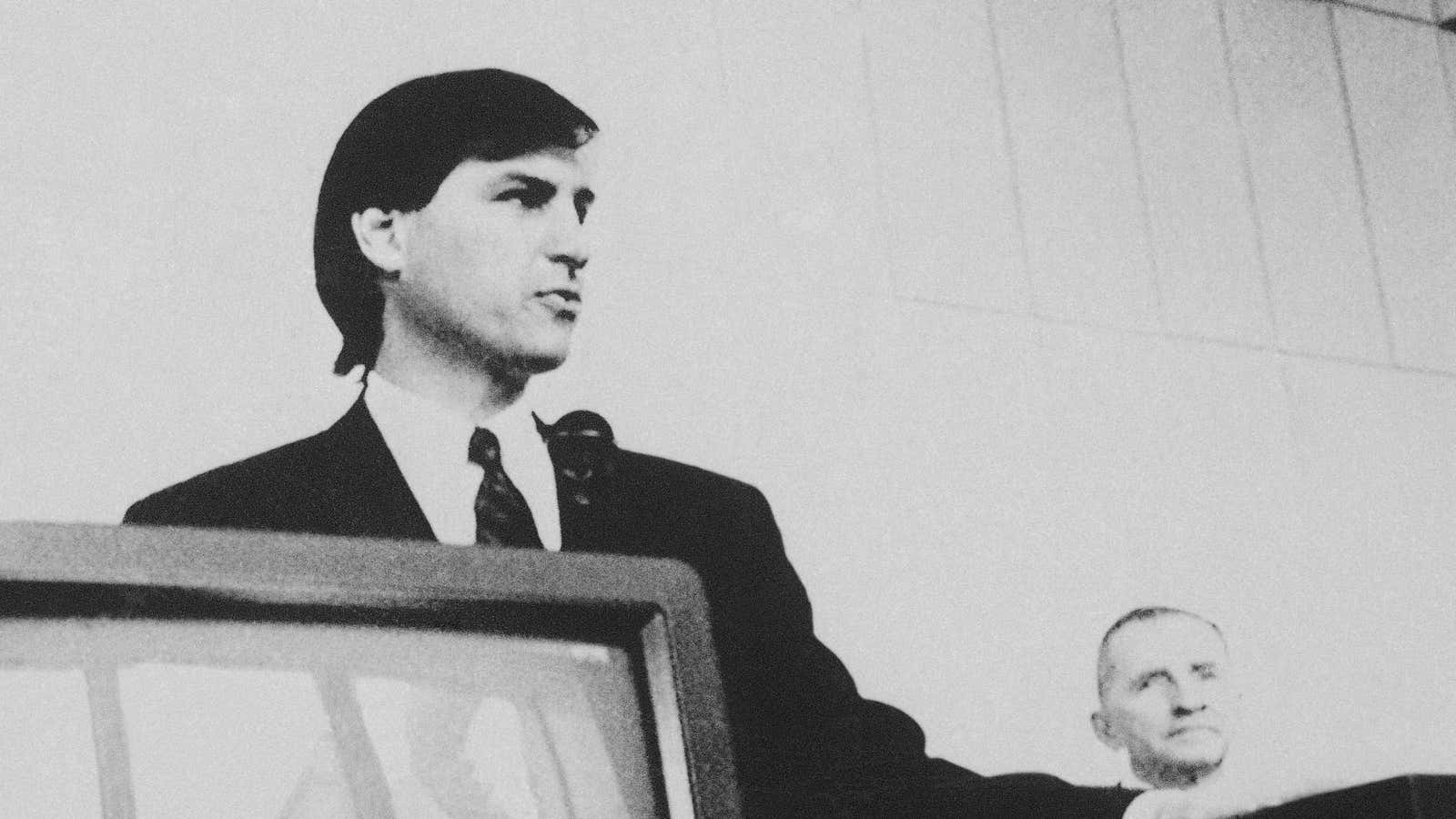

Wherever the next big thing comes from, it’s likely to be from entrepreneurs and designers who are not steeped in existing ways of thinking in Silicon Valley, in part because they’re young—Steve Jobs was 28 when he began working with Esslinger. ”At Frog, our best ideas came from our youngest designers, fresh out of school,” says Esslinger. In part, he says, this is because of a willingness to fail—something that is, at least, still part of American culture. “In Europe you learn not to fail, and in America you fail to learn. You need failure.”

Footnote

(1) Esslinger speaks from experience: When developing the design language for early Macintoshes, he had to convince Jobs to adopt a more expensive manufacturing process in order to get the sides of the cases for Apple computers to be perfectly straight. (Injection molding processes demanded a 1 degree angle to otherwise boxy cases, so that molds could pull away from the cases easily.)

Subtle touches like that are now an Apple trademark, but refinement can only take a company so far, and the conservatism inherent in how design groups within companies must answer to their bosses means that companies tend not to innovate, says Esslinger.