It’s a good week on Wall Street.

Investment banks stand to earn at least $500 million in fees on Verizon’s titanic $49 billion bond deal, which launched Wednesday to strong demand. Verizon is borrowing the money to help come up with $130 billion it needs to fork over to Vodafone to convince its British partner to hand over its 45% stake in Verizon Wireless. The lucrative US wireless provider had been a joint venture between the two companies.

The sheer size of the bond deal—it’s almost three times the size of Apple’s $17 billion offering from back in April which was the previous record holder for largest bond—suggests that Verizon was in something of a rush to get the bond deal done in one fell swoop. That makes sense. With the Federal Reserve widely expected to start easing up on the amount of support it is giving to the markets at its policy meeting later this month—by tapering its bond purchases—interest rates could indeed go higher. And that would mean borrowing such a huge hunk of cash would be much more expensive.

On the other hand, the Verizon deal may already reflect some of the new realities of a bond market that relies on the Fed a bit less. After all, investors were able to extract a higher-than-average interest rates from Verizon. The yield on the 10-year bonds the company sold, for example, were about 5.19%. That’s more than 2.25 percentage points over comparable Treasury notes. Bloomberg notes that AT&T sold similar 10-year notes in December and had to pay only 1.20 percentage points over Treasurys.

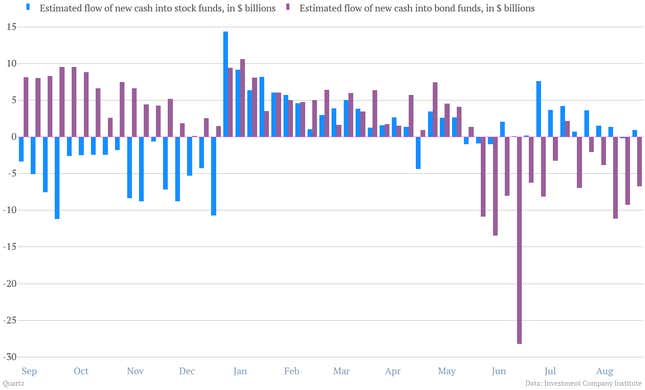

Now the size of the deal would likely mean that Verizon would have to pay some kind of premium. (For a $49 billion offering to succeed, it needs to coax a lot of people to buy.) But it’s also true that investors have been starting to move away from fixed-income products and tilt their money a bit more back into stocks. Such dynamics should, by rights, translate into higher borrowing costs for corporates. Here’s a look at US mutual fund flows from the Investment Company Institute, a trade group. You can see how last year at this time investors were still yanking money from stocks and putting it into bonds, the current situation is precisely the opposite.

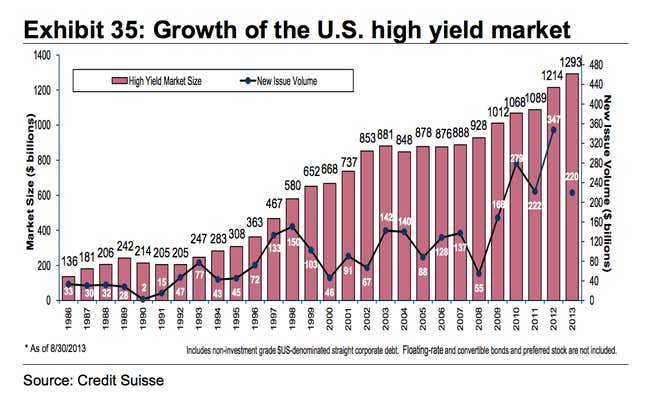

Will the uptick in rates crimp the prospects for US corporates? Hardly. American companies have been bingeing on cheap debt since the crisis hit, driving issuance of bonds to fresh peaks, even for riskier companies that issue junk, or “high-yield” bonds. This Credit Suisse chart lays out the trend nicely.

Corporate cash stockpiles are also plenty fat. That means the large companies that tap the bond market generally already have all the cash they need to fuel expansion, even if the days of super-cheap money will soon be a thing of the past.