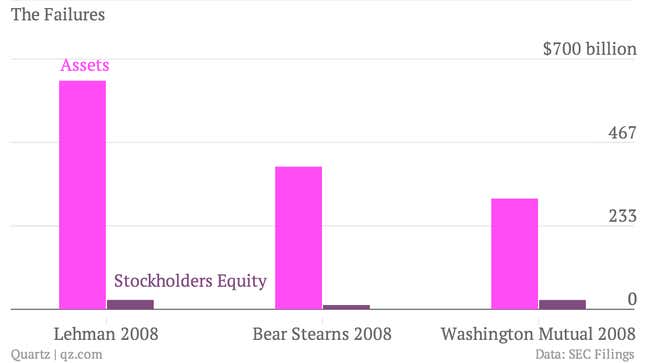

Today is the fifth anniversary of the failure of Lehman Brothers, the popular starting point for the narrative of the financial crisis. Lehman, along with other financial institutions that went under, all had something in common: The massive gap between their assets (loans they bought or investments made) and the equity of their companies.* What bridged the gap was borrowed money, from depositors or overnight lenders, and when the housing markets went south, they couldn’t afford to both absorb their losses and pay their creditors.

Hence, disaster:

Lehamn was borrowing some 26 times its equity; Bear Stearns, 34 times; Washington Mutual nearly 12 times. Keep in mind that all the numbers in these charts are self-reported, and likely to understate borrowing. The bankruptcy examiner in Lehman’s case found the bank used a lending scheme to move some $50 billion off its balance sheet in an effort disguise how much money it was really borrowing.

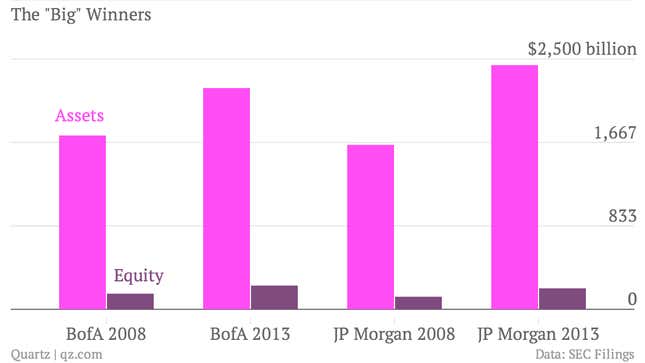

So what’s changed since then? Let’s look the five largest US banks before and after the crisis. Here are the two largest: Bank of America and JP Morgan. Both grew enormously after the crisis while reducing their leverage—but not by too much.

Then there are the next three: Citigroup, Wells Fargo and Goldman Sachs. Citi and Goldman Sachs both have shrunk in terms of assets, while Wells Fargo more than doubled in size. All reduced their leverage as well, Goldman somewhat dramatically—it borrowed 28 times equity in 2008 and 12 times equity this year (that’s the highest current leverage ratio of the largest five banks).

The good news is that all the largest banks are better capitalized than they were five years ago. But while new regulations—not to mention the generous government cash injections that kept the banks functioning through the crisis—forced them to solidify their capital positions, the improvement has been fairly small. Many experts believe the big five’s average capital holdings of 9.7% of total assets is too low, and should be upped significantly. The Federal Reserve, which estimates capital ratios much lower than what the banks report publicly, thinks the current standard should be doubled. Allowing these banks to pay millions in dividends over the last five years rather than retaining them as equity may turn out to be a big mistake.

Re-capitalizing isn’t the only solution; new rules around mortgage lending, derivatives clearing and the winding down of shaky banks, along with a higher level of regulatory scrutiny (hello, JP Morgan) have all changed the way banks do business. But those gains are small enough to be reversed when the next crisis comes along.

“People mistake safer for being safe,” Neil Barofsky, the former official charged with auditing the US bank bailout, told Quartz. “It’s in better shape, that doesn’t mean we’ve achieved a level of sustainability.”

*We’re eschewing leverage calculations that use risk-weighted capital here in favor of simple leverage ratios because they’re, uh, simpler, and more importantly, harder for banks to game.