Posh diners are swallowing up yet another species from the ocean: the European seabass. The population of the once populous fish has plummeted 32% since 2009 and has hit a 20-year low, according to the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES), a European science council. The group says fishermen from the UK, Channel Islands, Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark and France should slash their combined catches of seabass by 36%.

How has yet another fish joined the list of threatened marine species? The European seabass—known as branzino or loup de mer in the US, and not to be confused with the Chilean seabass—is popular year-round in Italy, particularly around Christmas, when fish are traditionally eaten. In the last decade or so, consumption has also taken off in Spain, Greece and Turkey, particularly during tourist season. More recently, it’s emerged as a British culinary craze, becoming the darling of celebrity chefs like Nigella Lawson, Gordon Ramsey and Jamie Oliver. Britons bought £30 million ($48 million) worth of seabass in 2012, an increase of more than 10% from 2011.

In fact, in all major markets, it’s usually eaten in restaurants (pdf, p.108), usually fancy ones. That’s due in part to its high price, but also because seabass filled in as severely overfished species like cod and haddock dropped off menus.

Around 150,000 tonnes were consumed globally last year, including nearly 2,500 tonnes of the tender white fish in the United States, according to National Marine Fisheries Service data.

But almost all of those seabass weren’t wild-caught; they were raised via sea cages, land farms and other farming methods (those include raising them in a nuclear reactor cooling system), most of which takes place in Greece, Spain and Cyprus. Even in the US, American chefs have taken a shine to farmed European seabass, even as they tend to poo-poo farm-raised fish of other species.

This might seem odd given that farmed seabass carries the risk of antibiotics-doping and unclean conditions. But it’s also much, much cheaper. Wild seabass currently fetches up to $30 per kilogram ($13.60 per pound), according to the latest market prices from Globefish. Farmed seabass cost around $13 per kilo, though it can go for as low as $4 per kilo.

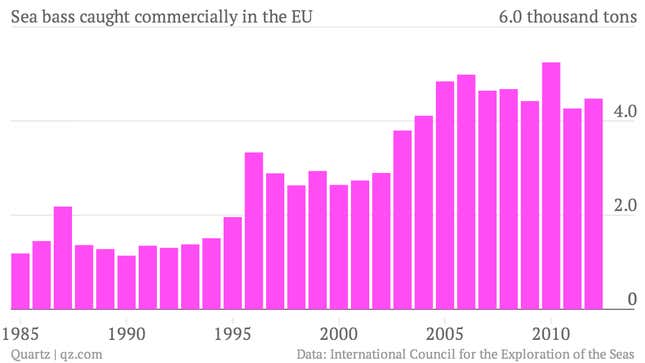

That huge premium probably has less to do with the Nigella and Gordon effect than the fact that wild fish are getting scarcer, fast. EU fishermen only caught 4,060 tonnes (4,475 tons) last year, down from the peak of 4,758 tonnes in 2010, and a fairly steady decline since 2006, when fishermen landed 4,522 tonnes.

ICES is asking EU fishermen to catch only 2,070 tonnes in the next year to help revive the seabass stock. That already isn’t sitting well with EU fishermen. “A cut of 36% would decimate us, I’m only catching around five fish a day and going down to two or three would put me out of business,” Andy Alcock, secretary of a British fishermen’s guild, told the Dorset Echo.

For now, the EU hasn’t set limits on seabass. But once it does, Alcock will have to move on to another fish whose days are numbered.