China pumped $3.4 trillion into China’s economy last year, according to a new report by credit rating agency Fitch. And for another fun number: local governments have amassed $3.3 trillion in debt, says a Chinese government-affiliated economist.

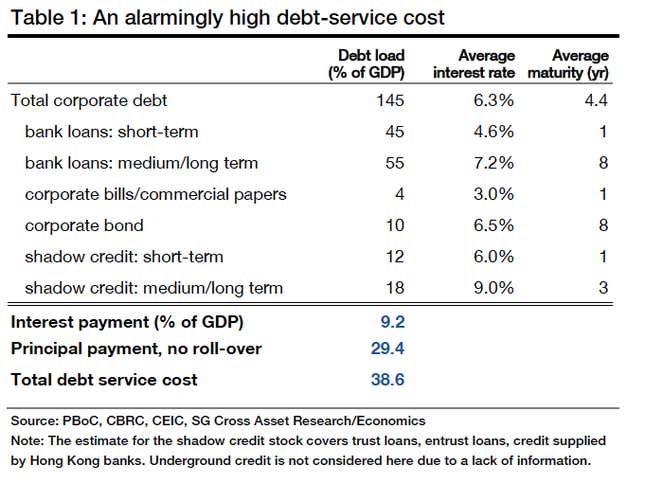

On their own, the numbers might be hard to grasp. But comparing what China owes on those loans to its GDP reveals that the country’s “debt service ratio” (DSR)—the proportion of interest and principal on loans that businesses owe against a country’s GDP—is now 38.6%, according to calculations by Wei Yao, an economist at Société Générale. That means that more than $3.2 trillion of the country’s GDP now goes toward paying down debts. Here are the details of Yao’s calculations from a note today:

Once businesses start taking out loans to pay old debts, a country enters a nasty cycle. As more loans chase more debts, less genuine investment creates less income and more debt, which perpetuates borrowing.

Eventually, something has to give. When this has happened with other countries in the past, the trigger was often a drying up of credit. No longer able to borrow to cover their debts, businesses defaulted.

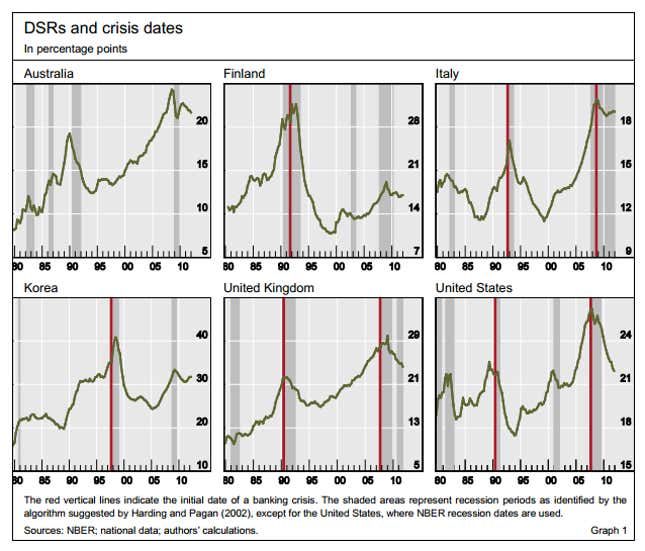

How does China stack up against those other countries in terms of its DSR? Yao points out that, compared with other countries whose finances collapsed, China’s 40% is “shockingly high.” For example, the US’s DSR was 27% over the 2008 to 2009 period, while Finland’s hit 30% before its finances imploded in the early 1990s. Only pre-1997 South Korea came in higher, at just over 40%:

How has China’s DSR climbed so much higher than that of other countries (save South Korea) while avoiding a financial crisis? Probably because people expect the central government to guarantee all this debt, says Yao.

The government has given them no reason to think otherwise. It swooped in to mollify people who lost money when their wealth management products (WMPs), shady investment products that repackage longer term loans for shorter periods of time, went bankrupt. In June, when two state-owned banks couldn’t pay their debts, the central bank stepped in. And, somehow, in the whole history of modern China, no enterprise has ever defaulted on a bond.

As long as people believe the government won’t let anything go bust, China can keep piling on trillions of dollars in debt and still be financial crisis-free. But if buzz about financial reform is anything to go by, the new administration is preparing to ever-so-gradually remove the state’s implicit guarantee. Forcing banks and businesses to recognize bad debt and accept losses is a good thing for the economy in the long run, but doing so in a meaningful way risks fomenting panic, which could trigger a financial crisis. It’s a gamble the government eventually must take. But as debt piles up, the odds of a financial crisis only get worse.