You know that old joke about the French not having a word for ‘entrepreneur’? It may soon be outdated.

France has long been one of the least entrepreneurial countries in the developed world. Just shy of 22% of French employees worked for the general government in 2008. (By comparison, the average for the 29 countries the OECD collected comparable data for was about 15%.)

And just 15% of French respondents to a recent EU survey on attitudes toward entrepreneurship said they had started or taken over a business, or were planning to do so. That’s was lowest among the 27 European Union countries where polling took place.

“Historically France has not been a particularly entrepreneurial country,” said Mariarosa Lunati, who heads up group that studies entrepreneurship data, among other areas, for Paris-based think tank that focuses on economic data for the group of wealthy nations.

But things may be changing. During the nadir of the global recession in 2009, France implemented a policy change championed by then-President Nicholas Sarkozy and his former finance chief Christine Lagarde, who now heads up the IMF. Known as a system of “auto-entrepreneurship,” the idea was to hack through France’s notorious layers of red tape in order to boost the creation of new businesses. It also exempts these independent small businesses from costly social charges until the firms are profitable.

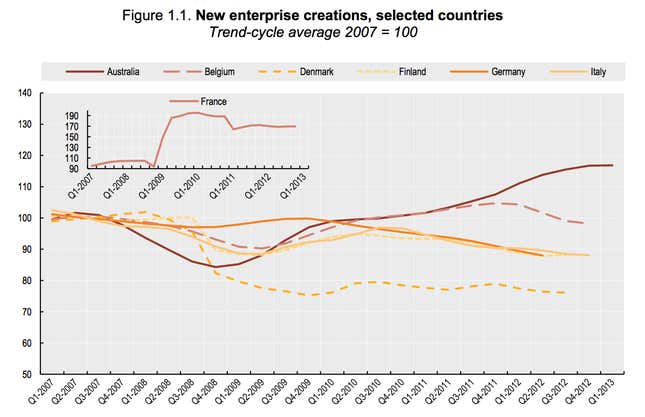

And, at least on paper, it seems to be working. Registrations of French auto-entrepreneurs surged once the policy took hold. Check out this chart of new enterprise creation, recently published by the OECD. France is in a class of its own.

Thanks to the surge in auto-entrepreneurs, France now looks ostensibly more entrepreneurial than a range of other countries, including the US.

Is this really a French entrepreneurial revolution? Kind of. Critics might point out that a big chunk of French auto-enterprises exist largely on paper. A report from France’s National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies found that of 2009’s 328,000 newly registered auto-entrepreneurs, only half were actually operating businesses. What’s more, their business income during their first year was three times less than that of businesses that were created under traditional guidelines. Auto-entrepreneurs often held other jobs, too.

In that light, auto-entrepreneurship is clearly not a panacea for France’s labor woes. But at the very least, the shift may have piqued more interest in running small businesses. The French public, and France’s startup community, bucked efforts by the current French government—led by Sarkozy’s successor François Hollande—to reduce tax exemptions for some more successful auto-entrepreneurs. To the extent that pushback reflects changing attitudes toward business in France—long colored by popular mistrust of the country’s highly concentrated corporate sector—that could be a very good thing.